Suffered under Pontius Pilate A Roman Prefect in the Creed's Christology

Suffered under Pontius Pilate A Roman Prefect in the Creed's Christology

In this time of the liturgical year we turn our attention to the suffering, death, and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. On Good Friday we commonly read Scripture accounts of Peter's denial, the treatment of our Lord Jesus by Caiaphas, the trial before Pontius Pilate, and the crucifixion and death on Golgotha. On Easter Sunday ministers preach on the discovery of the empty tomb, the resurrection of the now glorified Lord Jesus and Christ's appearance to His disciples. Each of these topics concerns the Lord Jesus Himself and His sacrifice to redeem the world. Indeed, we focus on the crux in the history of our redemption. The unjust suffering and death of our guiltless Lord, and His consequent glorious resurrection are poignantly summarized in the Apostles' Creed: "…suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried, He descended into hell. On the third day He arose from the dead."

Though the Apostles' Creed is generally considered an apt symbol of the Christian faith, some have questioned the reason for mention of Pontius Pilate. One critic states: "It is at first sight rather puzzling that Pontius Pilate should have been vouch saved a position in the Church's confession of faith."1 Karl Barth's reply is representative of the commonly found, yet insufficient answers: The simple answer can at once be given: it is a matter of date. The name of the Roman procurator in whose term of office Jesus Christ was crucified, proclaims: at such and such a point of historical time this happened.2 Though we shall see that "suffered under Pontius Pilate" was employed in the early church to emphasize the historicity of Jesus' incarnation, death and resurrection, the role of Pontius Pilate is much more extensive than this. In explaining the reason for the presence of this expression in our creed, I shall point out that Pilate's role is to make manifest the saving work of Jesus Christ; therefore the expression is rightly located at the centre of the Christology in the creed. This function of Pilate is first evidenced in the gospel writers. Using the common Reformed model of Christ's tripartite office of king, prophet, and priest, we shall note that in the gospels Pilate's role is not merely as official judge to ensure the historical reality of Christ's passion and death, but to display key aspects of the Christology. It is Christ's innocence which Pilate ascertains, thus revealing the guiltlessness of the man who "died for the sins of many." At the same time it is this innocent man who is found guilty by Pilate, so that our Lord is condemned to crucifixion and death. It is the same Pilate who records the prophetic resurrection after three days, thus manifesting Christ's glorification. Nevertheless, Pontius brings about the humiliation of Jesus, turning over this "King of the Jews" to the chief priests for punishment. Yet while he brings about the Saviour's humiliation, he also makes His true kingship, to be revealed, and thus points to the glorious King of the resurrection. Having noted the presentation of Pilate in the gospels as emphasizing Christ's redemptive work is the primary reason for his inclusion in the creed, we shall verify this function by considering the Christological purposes given to the expression by the apostolic fathers and apologists of the first centuries.

Pilate's Prefecture of Judea⤒🔗

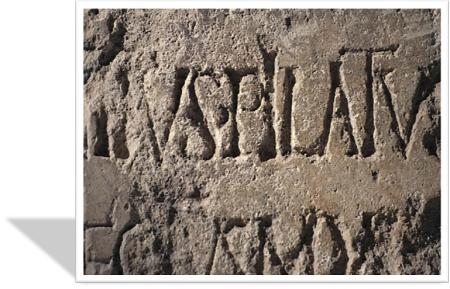

Pontius Pilate succeeded Valerius Gratus as prefect of Judea, which had come under Roman rule in A.D. 6. He held this difficult post from A.D. 26-36, when he was recalled to Rome. The prefecture required an able politician, one who could impose the Roman rule upon a nation which stubbornly clung to its religion. However, according to the Jewish historians Philo (b. 30 B.C.) and Josephus (b. A.D. 37), Pontius was a stubborn and inflexible administrator, often given to violence and corruption. Josephus provides three instances of Pilate's maladministration and insensitivity to the Jewish religion. Shortly after his arrival, Pilate had ordered the Roman troops to place ensigns of Caesar in the temple of Jerusalem (Jewish War 2.169), an act which was certain to arouse the indignation of the Jews who forbade images and statues according to the second commandment. On another occasion (Jewish War 2.175) Pilate was said to have employed moneys taken from the sacred treasury in the temple to finance the building of an aqueduct; the ensuing uproar was ruthlessly quelled. It was the cruel and systematic slaughter of the Samaritans who had gathered on Mt. Gerizim (Jewish Antiquities 18.35) which prompted the Syrian governor Vitellius to summon the prefect to the capital (18.88), and Pontius arrived at Rome shortly after Tiberius' death in the spring of 37. The alleged suicide of Pontius in A.D. 39 is recorded by Eusebius (Ecclesiastical History 2.7).

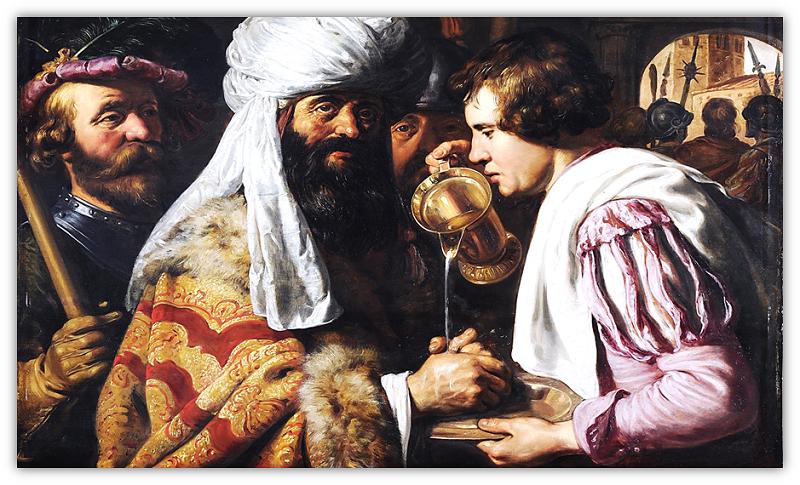

If the Jewish historian's pejorative depiction of Pilate is accurate, then it should surprise us that the gospel writers make little mention of the friction between Pilate and the people of Israel (pace Luke, ch.13:1). To be sure, in the gospels Pilate is represented as wishing to gain politically from Jesus' arraignment: he worries about the Jews' threat to report Pilate's leniency to Caesar (John 19:12); he makes a friend in Herod by sending Jesus Christ to him (Luke 23:6f.); and for fear of the crowds he delivers Jesus up (Mark 15:15).3 Yet the gospel writers do not depict Pilate in such a light as to denigrate the trial as a common sham. The purpose of the passion narrative is much deeper: to emphasize Christ's role in redemptive history.

Pilate as Presented in the Gospels←⤒🔗

The depiction of the Roman prefect in the passion narratives of the apostles is such as to place the Lord Jesus in the centre. A brief consideration of Christ's tripartite office of king, prophet, and priest, when He is tried and condemned by Pilate, reveals the Christological significance of the prefect's behaviour, thus providing the Scriptural basis for his inclusion in the creed.

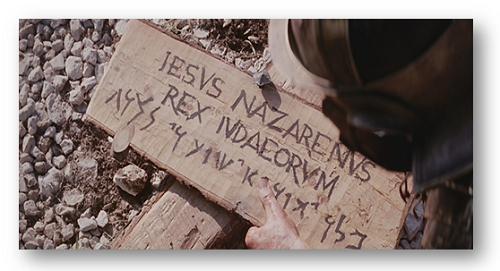

The role of Pilate in manifesting the kingship of Jesus Christ is clearly evidenced. When he first faces Jesus, the Roman prefect questions Him regarding the charge for which He is arraigned; yet later he asserts Christ's kingship by means of the superscription of the cross. Pilate commences his interrogation with the words: "Are you the King of the Jews?" We all know well the reply of Jesus, "You have said so" (Matthew 27:11; Luke 23:3).

In his more exhaustive report of the interrogation (John 18:33-38), the apostle John also emphasizes the kingship of Jesus. The Lord makes the profession (18:36): "My kingship is not of this world; if My kingship were of this world, My servants would fight, that I might not be handed over to the Jews; but My kingship is not from the world." Thus to John the role of Pilate is to elucidate the function of Christ as the King. Indeed, it is John who ascribes to Pilate the statement "Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews." In chapter 19:21 the chief priests request Pilate to alter the title into an alleged claim.

Pilate's refusal to comply accentuates the lordship of Jesus: "What I have written I have written (19:22)." In short, the very man who hands Jesus over to the Jews to be crucified bears witness to His kingship. It is this Christological element of king which John brings out in reporting Pilate's behaviour at the trial.

In the gospels Pilate also reveals Jesus' role as prophet. For Pilate figures in the unsuccessful attempt of the chief priests and Pharisees to prevent the prediction from coming true: "After three days I will rise again." According to Matthew 26:61-64, Jesus is brought before Caiaphas on the charge of having prophesied: "I am able to destroy the temple of God, and to build it in three days." This claim is not denied (cf. Matthew 24:1 f.). Matthew tells us (27:62-66) that it was Pilate who grants the chief priests to secure the sepulchre by setting a guard and sealing the stone; thus his role regarding the verification of Christ's prophecy is complete. Hereby Pilate functions as an official witness to the resurrection, to the realization of Jesus' prophecy.

Christ's redemptive task as the great High Priest in sacrificing His own life is the most important aspect of Pilate's role for the evangelists. The prefect is the agent who condemns the innocent man, to bear the sins of the world. In this regard, Pilate must first ascertain the innocence of Jesus, and then condemn Him – though innocent – to death. This role of Pilate is predominant throughout the gospels.

The innocence of Jesus Christ is repeatedly avowed by Pontius, especially in the gospel of Luke. In chapter 23:4 we read: "And Pilate said to the chief priests and multitudes, 'I find no crime in this man.'" In chapter 23:16 Luke depicts Pilate as being emphatic: "…After examining him before you, behold I did not find this man guilty of any of your charges against him." And again: "I have found in him no crime deserving death" (Luke 23:22). Similarly Mark (14:14) and John (18:38, 19:4) record Pilate's pronouncement of Christ's innocence. Even Pilate's wife had dreamt of the "righteous man," and tells her husband to have nothing to do with Jesus (Matthew 27:19)! Pilate is fully aware of, and openly declares, Christ's guiltlessness.

Nevertheless Pilate condemns Jesus Christ to death. In so doing he is an agent in Christ's unique sacrifice to atone for the sins of mankind: an innocent man had to bear the wrath of God. Luke writes (23:24ff.): "So Pilate gave sentence that their demand should be granted … Jesus he delivered up to their will." The parallel account in Matthew 27:26 reads: "Having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified." Though he had declared Him innocent, Pilate condemns Jesus to death. Thus the gospel accounts of the trial and crucifixion under Pontius Pilate emphasize the three-fold task of Jesus as the king, prophet, and priest.

Already in the first decade after Christ's ascension, when the apostles preached the gospel of His death and resurrection, the role of Pilate in revealing Christ's blamelessness and in condemning Him nonetheless is again stated. In the speech of Peter at Solomon's portico, the Roman prefect is cited, not to provide an historical context of Christ's death, but to stress the guiltlessness of Christ Jesus, "whom you delivered up and denied in the presence of Pilate, when he had decided to release him" (Acts 3:13; cf. 13:28). While in this passage the official is mentioned as having determined Christ's innocence, in the prayer of the apostles in Acts 4:27, Pilate is mentioned as one of those who wrongly sought to condemn and crucify Jesus, thus fulfilling God's eternal plan. In these passages it is Christ's innocent suffering and unjust condemnation to death which is central.

The Expression used by the Apostolic Fathers and Apologists←⤒🔗

A brief synopsis of the expression "suffered under Pontius Pilate" as employed by the apostolic fathers and apologists shows the continuing Christological purpose of the Roman prefect in the history of the church.

We may first note that the clause, "suffered under Pontius Pilate" is considered to be one of the first to become fixed as a credal expression. An important text in our understanding of the development of the creed, and one which contains the phrase under discussion is 1 Timothy 6:13. In his instruction to Timothy, Paul writes: "In the presence of God who gives life to all things, and of Christ Jesus who in his testimony before Pontius Pilate made the good confession, I charge you to keep the commandment…"4 Here the expression appears to be one of the many stock expressions concerning Jesus Christ which became common in the first decades after Christ's ascension.

In fact, 1 Timothy 6 refers to what was probably the doctrinal preparation for baptism.5 Similar creed-like expressions regarding baptism are found in the writings of the apostolic fathers and apologists. For example, in the Apostolic Tradition (ch.21) of Hippolytus (c. 217), the baptizand is asked: "Do you believe in Christ Jesus, the Son of God, Who was born by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate, and died, and rose again on the third day…" also in connection with baptism, in the Apology (1.61) of Justin Martyr (c. A.D. 100-165) we read: "Moreover, it is in the name of Jesus Christ, Who was crucified under Pontius Pilate … that the enlightened man is baptized." The expression gains specific historical significance in Apology 1.13: "Jesus Christ, Who was crucified under Pontius Pilate, the governor of Judea in the time of Tiberius Caesar," an addition perhaps prompted by the historiographical tag in Luke 3:1-6. These passages merely demonstrate the early credal formation of the expression, "suffered under Pontius Pilate."

Justin's accuracy in dating the suffering, death, and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ should not go unnoticed, for in the second and especially third century, the challenge against the reality of Christ's suffering as true human being is made by the Docetists. Docetism (from the Greek dokein, "to appear, to seem") is the belief that Jesus Christ merely appeared to suffer and die, and that His physical body was a mere phantom. It does not question the dating of the suffering under Pilate, rather it questions the human nature of our Lord Jesus Christ. In other words, the Docetists queried the dual essence in the Christology. The confession of the two natures of Jesus Christ was destined to become a matter of debate from the second to the fourth centuries, in which Pontius would play no minor role.6

The notion that Justin Martyr frequently employed the expression "suffered under Pontius Pilate" for more than historical reference, is reinforced by the revelation-historical use of it in the Dialogue with Trypho, ch.85. In the context of explaining Psalm 24:7 ("Lift up your heads, O gates … that the King of glory may come in") as referring to the glorification of Jesus Christ after His death, Justin uses the credal phrase again: "…the true Son of God, who was the First-born of all creatures, who was born of a virgin, who suffered and was crucified by your [Trypho was Jewish] people under Pontius Pilate, who died and then, after His resurrection from the dead, ascended into Heaven." Though the writer uses the by now conventional phrases, it is noteworthy that he does so in a Christological context.

In the writings of Ignatius of Antioch, who was a martyr during the emperorship of Trajan (c. 98-117), the expression, "suffered under Pontius Pilate" is also employed to champion the reality of Christ's suffering and death in the flesh, and to stress His human nature. Thus, for example, we read in the Letter to the Trallians7, of "Mary's Son, Who was truly born, ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died…" Likewise in his Letter to the Magnesians 11, Ignatius expresses the hope that his readers will "be convinced of the birth and passion and resurrection which took place at the time of the procuratorship of Pontius Pilate; for these things were truly and certainly done by Jesus Christ…"8 Hereby Ignatius wishes to show that Jesus Christ did not experience suffering and death in appearance only, but in true human essence. Thus for him too, the expression "suffered under Pontius Pilate" does much more than to date Christ's incarnation in the history of this world; Pontius Pilate elucidates Christ's two natures, especially His humanity.

In this regard the phrase regarding Pontius Pilate is closely connected to the preceding one, "born of the virgin Mary," which also expresses Christ's humanity. Thus Irenaeus, also refuting the Docetists, writes of Jesus Christ who "…condescended to be born of the virgin, He Himself uniting man through Himself to God, and having suffered under Pontius Pilate, and arising again…" (Against the Heresies 3.4.2). Clearly, then, the credal phrase was employed to champion an important element of the Christology, namely the humanity of Christ. It may be noted in passing that even today, when redaction and history critics question the truth of Jesus Christ's existence, the expression "suffered under Pontius Pilate" enters into the discussion.9

Conclusion←⤒🔗

Our examination of the role of Pontius Pilate in the gospel narratives, and of the development of the credal expression shows that in the history of redemption the prefect serves a greater purpose than that of placing Jesus' incarnation in the context of human time. Pilate is an agent in Christ's ultimate sacrifice to bear the wrath of God against mankind. The true and righteous man, our Lord Jesus, was declared innocent and yet condemned by the earthly judge, Pontius Pilate. To use the words of Calvin, the Roman prefect is mentioned in the creed "not only to affirm the faithfulness of the history, but that we may learn what Isaiah teaches: 'Upon Him was the chastisement of our peace, and with His stripes we are healed' (Isaiah 53:5).10

Add new comment