The Missionary Zeal of Calvin

The Missionary Zeal of Calvin

In the minds of many people the words ‘missionary’ and ‘Calvin’ have little or no association with each other. When they think of John Calvin, the last thing they think about is a man characterised by missionary zeal. Even scholars who ought to know better, share this outlook.

For some, the (supposed) problem is the character of Calvin himself. Two examples will illustrate the point. Historian Will Durant in his 11 volume History of Western Civilisation said of Calvin: ‘We shall always find it hard to love the man, John Calvin, who darkened the human soul with the most absurd and blasphemous conception of God in all the long and honoured history of nonsense’. Even more blunt is the assessment of Erich Fromm that Luther and Calvin ‘belonged to the ranks of the greatest haters in history’. Such a man would have no interest in mission.

Others, whose evaluation of Calvin would be much more positive, nevertheless argue that in practice he, like many of the other Reformers, took little interest in mission. Missiologist Gustav Warneck attributed this failing to the Reformers’ belief in predestination. Thus he writes:

We miss in the Reformers, not only missionary action, but even the idea of missions ... because fundamental theological views hindered them from giving their activity and even their thoughts a missionary direction.

Such views are to be found in the recent study of the history of Protestantism by Oxford scholar Alister McGrath, entitled Christianity’s Dangerous Idea. Arguing that in its formative phase Protestantism had little interest in mission or evangelism, he goes on to assert that ‘Neither John Calvin nor Martin Luther had any particular concern to reach beyond the borders of Christendom’. Calvin’s goal, according to McGrath, was ‘primarily that of the reformation of Catholics – that is to say, the conversion of people from one form of Christianity to another’. The Reformer’s approach to the situation in France is said to be an example of this model of ‘evangelism’.

In McGrath’s view, therefore, Calvin did not think in terms of seeking the conversion of the unconverted. The Catholics of France were not heathen who were in need of evangelisation: they were Christians in need of reformation. McGrath asserts, ‘Both Luther and Calvin were emphatic that Catholicism and Orthodoxy were Christian’. The accuracy of that portrayal of Calvin would, however, be difficult to square with his statement in a sermon on Acts 2:41-42, preached on 26 January, 1550, that ‘the church does not exist in the Papacy’. McGrath goes on to claim that the propagation of the Christian faith was, according to Calvin, the duty of the ‘Christian’ state, not of the church. Such a presentation of Calvin’s thinking suggests strongly that to ascribe ‘missionary zeal’ to the Geneva Reformer is to misunderstand his outlook entirely.

In this paper we will argue that in fact Calvin was a man who manifested great missionary zeal, contrary to the views which we have just noted. Our response will consider two issues:

- The practical expression of Calvin’s missionary zeal.

- The theological foundations of Calvin’s missionary zeal.

1. The Practical Expression of Calvin’s Missionary Zeal⤒🔗

The caricature of Calvin as a hater of the human race cannot stand up to any serious scrutiny. He consistently used his influence to make Geneva a city of refuge for a wide diversity of people from all over Europe. Protestant refugees fleeing persecution could be sure of a welcome in Geneva.

Although the influx of new residents presented practical problems for a small city with limited resources, the influence of Calvin and his supporters in the city councils ensured that thousands of refugees were accepted. In the course of the 1550s ‘Geneva had established an international reputation as a haven for those seeking safety on account of their religious views’. Indeed it was one of the factions opposed to Calvin, the Perrinists associated with Ami Perrin, who pursued a policy that can be characterized as ‘Geneva for the Genevans’.

Geneva, however, was not merely a reception centre for religious refugees. It was also a centre for the training and sending out of missionaries. John Knox’s view of Geneva has become famous: the city was ‘the most perfect school of Christ which has been seen on earth since the days of the apostles’.

As Philip Hughes observes,

Here able and dedicated men, whose faith had been tested in the fires of persecution, were trained and built up in the doctrine of the gospel at the feet of John Calvin, the supreme teacher of the Reformation.

Calvin himself recognized the importance of Geneva in relation to missionary endeavor, a recognition that entailed danger and hardship for himself. In a letter written on 7 May, 1549, to Heinrich Bullinger in Zurich, Calvin puts the matter in these terms: “If I wished to regard my own life or private concerns, I should immediately betake myself elsewhere. But when I consider how very important this corner is for the propagation of the Kingdom of Christ, I have good reason to be anxious that it should be carefully watched over”.

Calvin’s missionary zeal was personally costly. Thus Geneva was, in the words of Philip Hughes “a dynamic centre of missionary concern and activity, an axis from which the light of the Good News radiated forth through the testimony of those who, after thorough preparation in this ‘school’, were sent forth in the service of Jesus Christ”.

As Douglas MacMillan noted some years ago, Geneva was from several points of view ideally placed to be a centre for European evangelism, especially to France. Geographically, it was only through Geneva that Protestant evangelists could make their way (relatively) safely into France. The other countries bordering France – Spain, Savoy, Lorraine and the Spanish Netherlands – were all in Roman Catholic hands. Politically, Geneva was allied with the Republic of Berne, a militarily strong city whose protection offered Geneva considerable security from hostile neighbours. ‘Within this city Calvin could set to work unhampered by too much outside interference; from it he could keep in touch with the rest of Europe’.

Calvin’s concern for the spread of the gospel led not only to the sending out of missionaries, it led to the sending of missionaries who were thoroughly trained and carefully prepared for the hardships and challenges which they would face. ‘He believed that a good missionary had to be a good theologian first’, writes Frank James. There could have been no better place of preparation than Calvin’s Geneva. Calvin’s missionary zeal did not result in a careless approach to the preparation of evangelists. Quite the opposite was the case:

He trained them theologically, tested their preaching ability, and carefully scrutinized their moral character. Calvin and the Genevan Consistory sent properly trained missionaries back to France to share the Gospel.

The Mission to France←↰⤒🔗

Historical and personal factors meant that Calvin’s missionary zeal expressed itself primarily in relation to his homeland, France. He was, after all, himself an exile in Geneva. His concern for the cause of the gospel in France and his deep sympathy for those who were suffering for their adherence to the Protestant faith were clear in the ‘Prefatory Address’ to King Francis I which Calvin included in the first edition of his Institutes published in 1536. He sought to present the king with a clear exposition of biblical truth, while at the same time refuting the main charges that were being leveled against Protestants by their opponents. The issues at stake could not, in Calvin’s opinion, be greater:

It will then be for you, most serene King, not to close your ears or your mind to such just defence, especially when a very great question is at stake: how God’s glory may be kept safe on earth, how God’s truth may retain its place of honor, how Christ’s Kingdom may be kept in good repair among us.

Opposition to the pure gospel in France did not abate, however, and for many the price of faithfulness was suffering, even to the point of death. Calvin and his associates in the church in Geneva did all they could to encourage their suffering brothers and sisters, above all by the training and sending of missionary pastors. The evidence for this great enterprise is supplied by the ‘Register’ of the Company of Pastors, which records their corporate actions, but given the great influence of Calvin in this body (if not in the civil councils at some periods), it is right to regard the Genevan missionary endeavour as an expression of Calvin’s missionary zeal.

The record is, inevitably, incomplete since there were times when it was considered too dangerous to include the names of those who were sent to France. The period for which most information is available runs from 1555 until 1562, when the wars of religion began in France. After that it was not thought expedient to include names of pastors in the minutes. For those years the Register records the names of 88 men sent out as gospel preachers, mainly to France. As Philip Hughes points out, however, many are not mentioned in the Register. For example, in 1561 the names of 12 missionaries are recorded, yet evidence form other sources indicates that in fact 142 were sent out.

The first of many entries in the Register relating to the dispatch of preachers occurs in 1555:

Maître Jean Vernou and M Jean Lauvergeat, who had been sent by the ministers of this church to the brethren who are scattered in several valleys in Piedmont, wrote a letter dated 22 April describing how the Lord was advancing his work there ... Vernou and Lauvergeat were commissioned to go and preach the Word there in response to the request of three brethren who were sent from there for this purpose.

Although these men went to Northern Italy, most went to France. The first recorded was Jacques l’Anglois, who went to Poitiers in response to a plea for help from the congregation there.

The scope of the work undertaken in France is truly amazing, especially when the size of Geneva is taken into account, and bears testimony to a powerful work of the Holy Spirit stirring the Genevan pastors to action.

Hughes provides a partial list:

we find them penetrating to the ancient city of Lyon, not far to the west of Geneva; southwards to Aix-en-Provence, Nîmes, Montpellier, Villefranche, Toulouse, Nérac, and the province of Béarn; along the Atlantic coast to Bordeaux, La Rochelle and the nearby islands, Nantes, Caen, Dieppe, and the Channel Islands; and in the north to Bourges, Tours, Orléans, Poitiers, Rouen and Paris; besides a host of smaller places too numerous to mention.

Goal←↰⤒🔗

The goal of each mission was to move from having an église plantée, which could be no more than a group meeting for prayer and Bible study, to having an église dressée, with its own consistory of local elders. In 1555 such an église dressée was established in Paris, followed by Poitiers (1555), Orléans (1557), La Rochelle (1558) and Nîmes (1561). By the beginning of 1562 the number of consistories in France had risen to a staggering 1785. The Geneva-directed evangelism was bearing abundant fruit.

Research in the archives of Geneva by Peter Wilcox has uncovered a wealth of letters exchanged by Calvin and some of the missionaries he sent out. Among other things, these letters show just how large some of the French Protestant congregations became. In a letter from Montpellier we read, “Our church, thanks to the Lord, has so grown and so continues to grow every day that we are obliged to preach three sermons on Sundays to a total of five to six thousand people”.

A pastor in Toulouse also wrote to the Geneva Consistory, “Our church has grown to the astonishing number of about eight to nine thousand souls”. Whilst the Reformed Church in France is rightly remembered for its endurance of suffering, the ‘church under the cross’, it should also be remembered for its fruitful evangelistic work. Some of its congregations were, in modern terms, mega-churches.

Calvin’s deep pastoral concern for the missionaries and those whom they served did not end when the preachers left Geneva. Letters such as those just cited were matched by many from Calvin and his associates giving advice and encouragement in what were often difficult circumstances. As Frank James puts it, ‘(Calvin) did not just send missionaries; he invested himself in long-term relationships with them’. Their welfare was of great interest to him and he put himself at their disposal for pastoral support.

Such support was vital, given the dangers which preachers of the gospel faced in France. In the consistory records their identities are often concealed behind pseudonyms and multiple identities: ‘Guy Moranges, alias la Garde’, and so forth. They traversed difficult routes and depended on sympathetic men and women for food and lodging. Services had to be held in secret and if a pastor’s identity was become too well-known (‘trop découvert’) he would have to move on. This happened, for example, to Antoine Bachelar who, after only two or three months in Lyons, was forced to return to Geneva. Even in writing to some of these men Calvin on occasion signed himself by the pseudonym Charles d’Espeville.

The cost of faithfulness could be high. The Register, for example, contains a letter dated 12 October 1553, and signed ‘Charles d’Espeville’, which is addressed to ‘the believers of certain islands of France’, the islands being those off the coast of Saintonge, in the west of France. A number of Reformed believers had written to Geneva requesting a pastor. Calvin, on behalf of the Consistory, replies, saying that an (unnamed) pastor, known to them, is being sent and also giving advice on church order.

Calvin concluded his letter thus:

Meanwhile take courage and dedicate yourselves wholeheartedly to God who has purchased you through His own Son at such cost, and surrender both body and soul to Him, showing that you hold His glory more precious than all this world has to offer. May you value the eternal salvation which is prepared for you in heaven more than this fleeting life. Therefore, and in conclusion, most dear brethren, we shall pray the good Lord to complete what He has begun in you, to advance you in all spiritual blessings, and to keep you under His holy protection.

The bearer of the letter, Philibert Hamelin, became their first pastor and ministered to them until his martyrdom in 1557.

One further example must suffice. On 16 August 1557, Nicholas de Gallars, a close friend of Calvin, set out to minister in Paris, a particularly dangerous assignment. En route his companion was captured and executed, although de Gallars escaped. On 7 September he wrote to the Consistory in Geneva to inform the pastors that three days earlier the congregation had been raided and some two hundred people, men and women, were languishing in prison. On 16 September Calvin wrote back to his friend, telling him that his first reaction on hearing the news had been one of horror: ‘I was almost prostrated with grief’. He quickly recovered himself, however, and took steps to try to alleviate the difficulties of the believers in Paris. With pastoral sensitivity, Calvin notes that he has kept the worst news from de Gallars’ wife, who is still in Geneva. He exhorts de Gallars to remain at his post for the sake of the congregation: their welfare is to be his paramount concern:

There is no need for us to emphasize how dear your life is to us; but if the safety of so many souls were not more dear to us, we should not be dear to you.

De Gallars is to work in harmony with his colleagues and is to take whatever action will most benefit the church. The Consistory also sent a lengthy letter to the Paris congregation to encourage them. Calvin ends his letter to de Gallars with these moving words: “May the Lord guide you and them in this crisis by the spirit of wisdom, understanding and uprightness; may He be present with you and with the cover of His wings protect, strengthen and sustain both you and the whole church”. Many other examples of Calvin’s zeal for the cause of the gospel in France could be drawn from the records.

The Mission to Brazil←↰⤒🔗

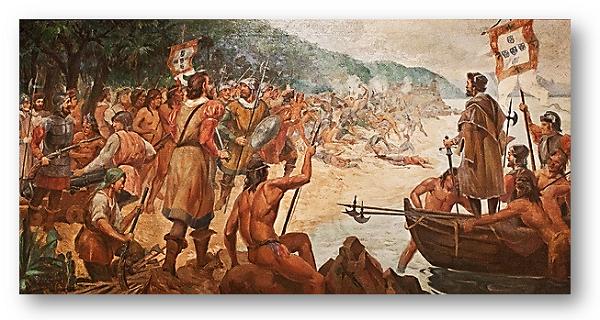

The focus of Calvin’s missionary zeal was France and, to some degree, the rest of Europe. He was also involved, however, in one overseas missionary enterprise – the Huguenot mission to Brazil. This mission, for all its ultimate lack of success, can be regarded as a testimony not only to Calvin’s own vision for the spread of the gospel but also to the missionary zeal which he kindled in those around him.

An entry in the Register for 25 August, 1556, reads:

On Tuesday 25 August, in consequence of the receipt of a letter requesting this church to send ministers to the new islands (Brazil), which the French had conquered, M. Pierre Richer and M. Guillaume Charretier were elected. These two were subsequently commended to the care of the Lord and sent off with a letter from this church.

The mission was sent in connection with an attempt to establish a French colony in Brazil and at the request of the founder of the colony, Nicholas Durand, sieur de Villegagnon. An enigmatic figure, with a colourful background, Villegagnon succeeded in gaining the support of Gaspard de Coligny, Grand Admiral of France, a supporter of the Huguenots who had not yet given open allegiance to the Reformed Church. As a result a small colony was established on a barren island at Guanabara (modern Rio de Janeiro).

Early difficulties led to an appeal for reinforcement from France and Geneva, including ministers ‘to bring the savages to the knowledge of their salvation’, as Villegagnon wrote in his letter. The ministers sent out were Pierre Richier, aged 50, a former Carmelite, and Guillaume Chartier, aged 30. Although Calvin left Geneva to mediate in a church dispute in Frankfurt the day after the decision was taken, he was kept fully informed of what was happening and the ministers took with them a letter from Calvin to Villegagnon.

At first all went well. The Lord’s Supper was celebrated in the colony according to the Geneva rite on 21 March 1556, with Villegagnon the first to receive the sacrament. The impact of the mission on the local Indians, however, was minimal. Richier’s first letter to Calvin described them as little better than animals, although another member of the expedition, Jean de Léry, was more hopeful of success in the long term and took pains to understand Indian culture and beliefs. This approach did give some openings for the presentation of Christian truth.

The situation in the colony deteriorated rapidly, however, as Villegagnon began to oppose the Reformed faith and challenged the pastors regarding both doctrine and practice. Chartier was sent back to Geneva to obtain Calvin’s opinion on various disputed points. Finally the colonists from Geneva rejected Villegagnon’s increasingly tyrannical rule and refused to labour for him. Several leaders of a conspiracy against Villegagnon were thrown into the sea, and the governor attempted, in vain, to starve the Genevans into submission. In the end Villegagnon expelled the Genevans, who lived for a short time among the Indians, with other colonists who had left Fort Coligny (as the colony was called).

A French ship, scouting for a location for a new Huguenot colony, rescued fifteen of the refugees, but when it got into difficulties, five agreed to return to the colony. Three (or four?) were arrested by Villegagnon and were required to answer several points of doctrine within twelve hours. The result was a confession of faith drawn up by Jean Bordel and also signed by Mathieu Vermeuil, Pierre Bourdon and André Lafon. The Confession of Guanabara (1558) was the first Protestant writing in the Americas and one of the earliest Calvinistic confessions. The next day Bordel and Vermeuil were thrown into the sea and Bourdon was strangled. They would not be the only missionary martyrs inspired by the faith proclaimed by John Calvin.

2. The Theological Foundations of Calvin’s Missionary Zeal←⤒🔗

Unfortunately, from our point of view, John Calvin did not write a systematic treatise on mission. Nevertheless significant theological principles which fostered his missionary zeal may be identified in his works. Drawing on his biblical commentaries, we will consider several of these theological foundations.

A. The Sovereignty of God←↰⤒🔗

It has often been claimed that belief in the sovereignty of God discourages interest in evangelism and mission. What is the point of evangelizing if salvation is determined solely by the decree of God? Calvin had in fact no difficulty in this regard. It was the decree of a sovereign God that ensured that those whom he had freely elected would certainly come to saving faith: “Although it is now sufficiently clear that God by his secret plan freely chooses whom he pleases, rejecting others, still his free election has been only half explained until we come to individual persons, to whom God not only offers salvation but so assigns it that the certainty of its effect is not in suspense or doubt”. This in no way nullifies human responsibility to believe. None will be saved without calling on the Lord for mercy, but it is God who motivates and enables that call:

When we receive the promises in faith, we know that then and only then do they become effective in us ... For by so promising he merely means that his mercy is extended to all, provided they seek after it and implore it. But only those whom he has illumined do this. And he illumines those whom he has predestined to salvation.

In is in fact the conviction that God will grant to his elect a saving response to the gospel message that enables preachers to proclaim the message with confidence. Calvin also asserts that the sending of the gospel by means of preachers is a token of the love of this sovereign God who has determined to raise up a people who know and love him. Commenting on Romans 10:15 (‘How shall they preach, except they be sent?’), Calvin writes:

Paul’s meaning is that when any nation is favoured with the preaching of the Gospel, it is a pledge and proof of the divine love ... It is certain, therefore, that God visits that nation in which the Gospel is proclaimed.

It is the will of God that the Gospel should spread throughout the world and so in times of adversity his people can take encouragement from the certainty of the divine plan. Commenting on Isaiah 2:3, Calvin writes,

Whatever may be the condition of your affairs, and though you should be oppressed by afflictions on all sides, still continue to cherish this assured hope, that the law will go forth out of Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem; for this is an infallible decree of God, which no diversity or change of events will make void.

In mission work, it is the sovereign Lord who provides the necessary opportunities for the spread of the gospel. Thus with reference to Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 16:9 (‘For a great door ... is opened’),

Calvin comments,

...the Lord was opening up an ‘entrance’ for him to spread the Gospel ... He calls it ‘effectual’ because the Lord was blessing his labour, and making his teaching efficacious by the power of His Spirit.

This principle holds true for the evangelistic work of the church after the age of the Apostles. Commenting on the phrase ‘A door was opened unto me’ (2 Corinthians 2:12), Calvin writes, “he means that an opportunity of furthering the Gospel had presented itself ... when an opportunity for edification presents itself, we should realize that a door has been opened for us by the hand of God in order that we many introduce Christ into that place and we should not refuse to accept the generous invitation that God thus gives us”.

The Genevan mission to France and Brazil were acceptances of God’s gracious invitation.

B. The Command of God←↰⤒🔗

Calvin had a big vision for the proclamation of the gospel because God’s plan of salvation is vast in scope. God in grace sends out his people to proclaim the gospel and to offer salvation to sinners on a worldwide basis. Thus in commenting on Paul’s exhortation to Christians to pray for all kinds of people, including rulers, in 1 Timothy 2:3,

Calvin writes, “... the apostle’s meaning here is simply that no nation of the earth and no rank of society is excluded from salvation, since God wills to offer the Gospel to all without exception. Since the preaching of the Gospel brings life, he rightly concludes that God regards all men as being equally worthy to share in salvation. But he is speaking of classes and not individuals and his only concern is to include princes and foreign nations in this number”.

The Church has an ongoing, worldwide mandate to spread the gospel. It is not accurate to claim, as scholars such as Alister McGrath do, that in Calvin’s view the Great Commission of Matthew 28 was only for the apostles and was fulfilled in their evangelistic ministries, leaving present-day evangelism as the province of the ‘Christian state’. In fact, when commenting on Matthew 28:18 Calvin decries the false apostolate of the ‘Roman Pope and his band’ and goes on to assert, “No-one can be a successor of the Apostles unless he uses his labours for Christ in preaching the Gospel. Whoever does not fulfil the role of teacher cannot rightly use the name of Apostle: this is the priesthood of the New Testament, to slay men by the spiritual sword of the Word, as a sacrifice to God”. The Great Commission continues to be God’s mandate for his Church, a principle exemplified in the various elements of the Genevan missionary endeavour.

C. God’s Unfolding Purpose←↰⤒🔗

A further element in the missionary thinking of Calvin and the Genevan Church has been identified by W Stanford Reid.

He notes,

Basic to all their thinking was the doctrine of creation. The sovereign God has made all things, and they are therefore His. And although through man’s sin alienation has taken place, it is the responsibility of those who are God’s people to bring creation back to Him. This is the mission of the Church until Christ’s return in glory.

Redemption has a cosmic scope and will therefore not be complete until the last day. The Church therefore has an ongoing task of mission to the world. As Calvin comments on Romans 8:21, “this passage shows us to how great an excellence of glory the sons of God are to be exalted, and all creatures shall be renewed to magnify it and declare its splendour ... God will restore the present fallen world to perfect condition at the same time as the human race”.

Until that day comes, evangelism must continue, in the certainty of God’s ultimate triumph. Calvin reiterates this point with reference to the building of the Church. In commenting on Micah 4:1-2 he says, “there is no Church, except it be obedient to the word of God, and be guided by it: for the Prophet defines here what true religion is, and also how God collects a Church for himself”.

On the same verse he also says,

there is no other way of raising up the Church of God than by the light of the word, in which God himself, by his own voice, points out the way of salvation. Until then the truth shines, men cannot be united together, so as to form a true Church.

The building of the Church necessitates the continued preaching of the gospel.

D. The Kingship of Christ←↰⤒🔗

Calvin’s zeal for mission is also rooted in his belief in the worldwide reign of the Lord Jesus Christ. By the preaching of the gospel sinners are brought into subjection to their rightful King. This reign of Christ is depicted, according to Calvin, in the Old Testament prophets. Commenting on Isaiah 2:4 (‘And he shall judge among the nations’), Calvin writes, “after the coming of Christ (God) began to reign by himself, that is, in the person of his only-begotten Son, who was truly God manifested in the flesh (1 Tim. 3:16) ... And again he confirms the calling of the Gentiles, because Christ is not sent to the Jews only, that he may reign over them, but that he may hold his sway over the whole world”.

The prophet Micah also, in Calvin’s view, speaks of the reign of Christ and the place of God’s Word in relation to it. On Micah 4:3 (‘For from Zion shall go forth a law’) he refers to Psalm 110 and says,

Christ does not otherwise rule among us, than by the doctrine of his Gospel: and there David declares, that this sceptre would be sent far abroad by God the Father, that Christ might have under his rule all those nations which had been previously aliens.

Later, on the same verse, he stresses that Christ’s reign has not spread as yet to the extent that God has decreed: “as the kingdom of Christ was only begun in the world, when God commanded the Gospel to be everywhere proclaimed, and as at this day its course is not as yet completed; so that which the Prophet says here has not hitherto taken place”.

The fulfillment of the prophetic visions is to be found in the Gospel records of Christ’s ministry, in particular his exaltation after the resurrection. Thus Calvin writes with reference to Matthew 28:18,

He particularly makes himself Lord and King of heaven and earth, because when He draws men into obedience by the preaching of the Gospel He is establishing the throne of His Kingdom upon earth, and when He regenerates His people to new life and calls them to the hope of salvation, He is opening the heavens to raise them to blessed immortality with the angels.

Such a prospect should act as a powerful motivation for the preaching of the gospel, as it clearly did in Calvin’s case.

E. The Christian’s Desire←↰⤒🔗

A final theological foundation for Calvin’s missionary zeal may be identified, namely the desire welling up within those who have experienced God’s saving grace that others would share in this glorious blessing. The gospel is a message that demands to be shared since it is the entrance into such great privileges. Calvin is well aware of this powerful motivation and expresses it vividly in his comments on Isaiah 2:3 (‘And shall say, Come’):

By these words he first declares that the godly will be filled with such an ardent desire to spread the doctrines of religion, that everyone not satisfied with his own calling and his personal knowledge will desire to draw others along with him. And indeed nothing could be more inconsistent with the nature of faith than that deadness which would lead a man to disregard his brethren, and to keep the light of knowledge choked up within his own breast. The greater the eminence above others which any man has received from his calling, so much the more diligently ought he to labour to enlighten others.

There is no place in Calvin, as there is no place in Scripture, for a selfish pursuit of salvation. The good news must be shared: Calvin held that truth unwaveringly and practised it with exemplary zeal.

Add new comment