The Heidelberg Catechism: An Historical Look

The Heidelberg Catechism: An Historical Look

The Setting⤒🔗

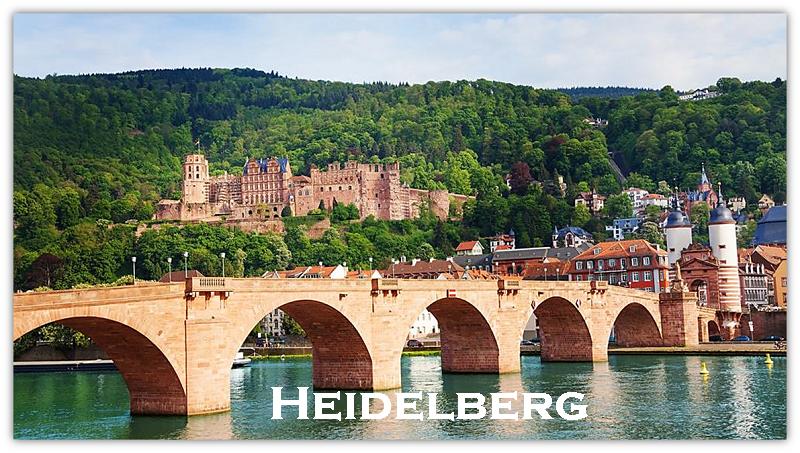

On the banks of the Neckar River in Germany there lies an old city that is full of charm and character. Few who walk its streets, adorned with antiquated buildings and old churches, or who travel the surrounding countryside of rolling hills and vineyards, come away indifferent to its spell. It is blessed with a moderate climate that includes mild winters and tempered summers. It is endowed with a center of learning that is in many ways the envy of Europe.

Yet this city is noted not just for its charm, but also for its history. It has witnessed the rise and fall of empires, both ancient and modern. It has experienced the tumult of war with its bitterness of defeat and its joy of victory. It has known eminent people: scholars, princes, merchants, craftsmen. Truly, over the centuries this city has been party to many great occasions and events.

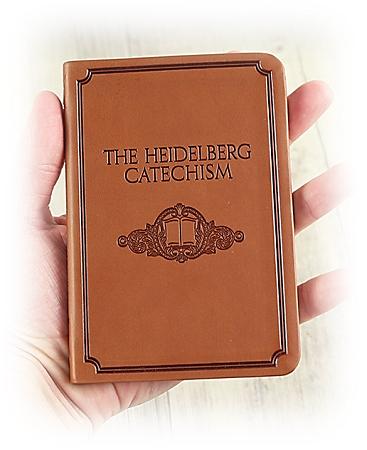

Which one was the greatest? No doubt many could debate that long and furiously, but for some no debate is necessary because they identify this city immediately with something that was written there over 400 years ago. What in particular? Was it a political manifesto, a philosophical treatise, an economic program? No, it was none of these; it was a religious work. Was it long and elaborate, filling hundreds of pages? No, it was rather brief and to the point. Was it deep and intellectual? No, it was easy to read, and for many, easy to understand. What was it? It was a catechism, a little booklet filled with all kinds of questions and answers. That does not sound like much. That hardly qualifies in the eyes of the world as a momentous event, or as something exceptional. But it was. It made that city famous throughout the world. And the name of that city? It is Heidelberg.

In the minds of many the Heidelberg Catechism, for that is the title of this little booklet, is still today this city's chief claim to fame. But you may wonder about that. Why was this Catechism written? By whom was it written? When was it written? Why is it famous? To answer all of these questions and more, we need to go back, far back into history, all the way back to the sixteenth century.

The Reformation Comes to Heidelberg←⤒🔗

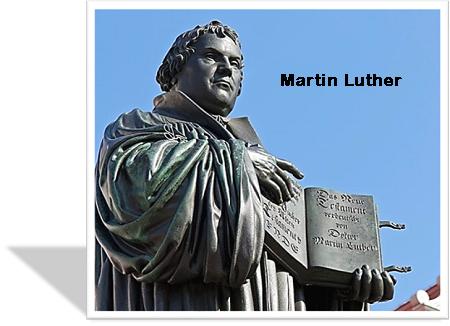

In the year 1544 Frederick II became the new ruler of that German mini-state called the Palatinate with its capital called Heidelberg. It was a tumultuous time. For over twenty years already, great religious debates had been echoing throughout the length and breadth of Europe. A monk by the name of Martin Luther had seriously disturbed the peace by challenging the mighty power of Rome. Like others before him, but now with much more effect, he had called the Pope to account for the doctrine and life of the Church. Far and wide his ringing cry of sola scriptura (by Scripture alone), sola gratia (by grace alone) and sola fide (by faith alone) could be heard.

It was in such a time that kings and kingdoms had to make great decisions. Would they continue to align themselves behind the Church of Rome or would they choose for the cause of Reformation? In the Palatinate the matter hung in the balance for some years. But with the arrival of the new elector, Frederick II, the scales soon tipped in favour of Reformation. In the years 1545 and 1546 the first Reformation decrees were issued.1

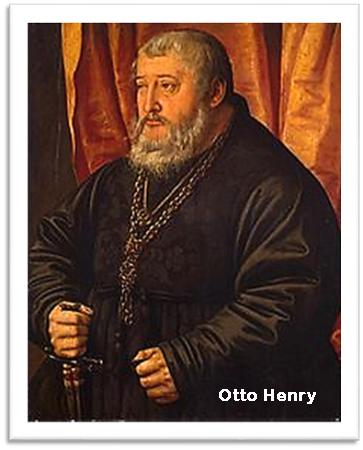

Still, it would be wrong to ascribe these changes to the forceful leadership of Frederick II, for all accounts seem to indicate that he was of the extremely cautious variety. It would be more accurate to say that Frederick was to some extent overtaken in these events by others. Reform was hastened because of the influence of Luther's chief associate, Melanchthon, because of the pressure brought to bear by the Elector's nephew, Otto Henry, and because of the leanings of the people.2

Of these three it would appear that the influence of Otto Henry was the most pervasive. Earlier he had lived at Neustadt and ruled over a small principality. In 1529 he had been converted to the Protestant cause and the following year he had helped form the Smalkald League, this being an alliance of princes who were determined to resist the attempts of the Emperor Charles V to crush the cause of Reformation. For his trouble, Otto Henry was deposed as a ruler in the Holy Roman Empire. He moved to Heidelberg and there he continued to espouse his cause.

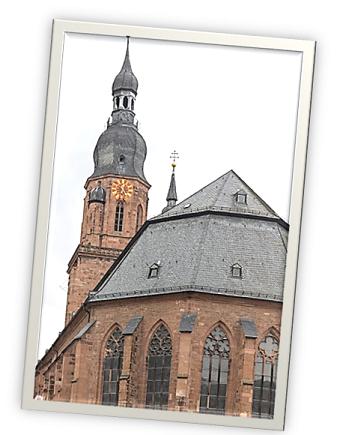

The result of his activities, as well as those of others, caused the Palatinate, and then especially its chief city, Heidelberg, to have a change of heart. On Christmas Day, 1545, the Lord's Supper was administered for the first time in a Protestant worship service in the chapel of Heidelberg Castle. Among the celebrants were Frederick II and his family. Shortly thereafter, on January 3, 1546, this service was repeated in the main church of Heidelberg, the Church of the Holy Spirit. The Reformation had officially come to Heidelberg!

Still, this coming was precarious, to say the least. All kinds of dangers loomed on the horizon. Conflicts between the supporters of Rome and Luther were the order of the day. On April 25, 1547, the Smalkald League, under the leadership of Elector John Frederick of Saxony, was defeated at the battle of Muhlberg. A number of Protestant electors were dethroned. As well, the forms of worship as prescribed by Rome were restored in an edict of the Emperor called the Catholic Interim of 1548.

How did Frederick II and his kingdom fare? On the whole he managed to weather the storm. Because of his cautiousness he had not supported the Smalkald League and that saved his electorship. Nevertheless, he left no doubts as to where his sympathies resided. When the mass was celebrated again in the Church of the Holy Spirit, Frederick II marched out. He remained committed to the cause of the Reformation and he decided to wait out the Emperor.

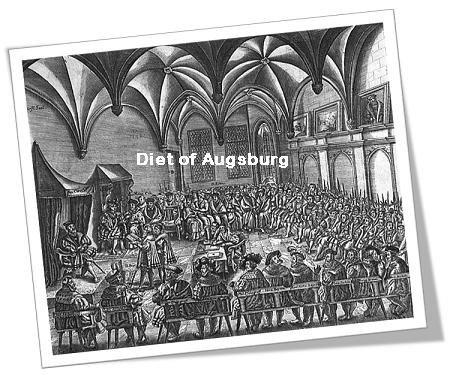

It turned out to be a wise choice, for seven years later, in 1555; the Catholic Interim was lifted and replaced by the Peace of Augsburg. It established the principle of freedom of religion in the Empire. Yet it was not complete freedom, for it was qualified by the condition cuius regio, eius religio (whose the reign, his the religion). This meant that if the prince was Roman Catholic, his domain would be Roman Catholic too. Still, in the case of Frederick II, whose loyalties were clearly on the side of Protestantism, it meant that in the Palatinate Protestantism became the recognized religion. The mass was abolished and the Protestant form of worship returned. In addition, Frederick II opened wide the doors of his kingdom to Protestants from other lands who were suffering from persecution. From England, France, and Holland, they came to live and worship freely.

A Period of Consolidation←⤒🔗

Although Frederick II lived to see the dawning of this new era of religious freedom, he did not live long enough to consolidate the new gains of this era. On February 26, 1556, he died and was succeeded by his nephew Otto Henry. With the ascension of Otto Henry to the throne of the Palatinate, the period of cautious Protestantism came to an end. He soon passed an edict rejecting all papal errors and proclaiming evangelical freedom. In the Church of the Holy Spirit he had all of the images removed, with the exception of one crucifix. He also decided to assess the state of the Reformation in the churches and to that end he brought together a visitation team of three men: Michael Diller, the court preacher; Henry Stoll, the pastor of the St. Peter's Church in Heidelberg; Johannes Marbach, a theologian from Strasbourg.

These men spent seven weeks investigating the life of the churches, after which they handed in their report. It was not very encouraging. It stated that the religious instruction of the youth was either totally lacking or much neglected. It concluded that the sacraments were held in rather low esteem. It went on at length about the moral indifference of the populace. It discovered a great deal of ignorance concerning the Word of God and its teaching. In short, the religious state of affairs in the Palatinate was far from healthy.

In response to this report Otto Henry decided that a number of initiatives were required. In the area of church government he appointed his three church visitors to draw up a Church Order which would give some structure to the life of the churches. The product that finally came from their hands called for a federated church consisting of a number of congregations but under the oversight of one consistory.

In the area of education, he approved the use of the Wurttemberg Catechism. It was a brief and rather elementary work consisting of 26 questions and answers, mostly on the sacraments. Otto Henry knew the shortcomings of this Catechism, but he believed that a start had to be made somewhere.

In the area of liturgy, he also made a number of changes. He promoted one of the least liturgical types of Lutheran worship. He curtailed the use of the church year and insisted that the clergy be called ministers, not priests. He discouraged the use of vestments and emphasized the need for more preaching and instruction. He had the church purged of images, side altars, crucifixes, and the other trappings of Roman Catholicism.

Finally, in the area of theological education Otto Henry also took some action. He established the Collegium Sapientiae (School of Learning), a precursor to the modern day theological seminary. Realizing that also in this area advise was needed, he invited Melanchthon to Heidelberg in the fall of 1577. The reformer's advice, which Otto Henry accepted, seemed to have gone in the direction of openness and tolerance to all the shades of Protestant theology, even the Reformed. In 1557 the Elector began to appoint a rather diverse faculty for his college. He recruited Henry Stoll and Michael Diller who were Melanchthonians; Peter Bocquin, who was a French Calvinist;3 Thieleman Hesshuss, a staunch Lutheran; Thomas Erastus,4 who at least on the Lord's Supper took a Zwinglian position. By all accounts it was a rather unique and curious collection of theologians, an experiment in ecumenical Protestantism.

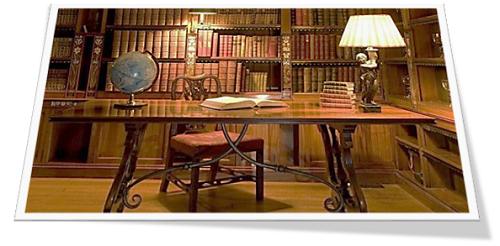

Mention should also be made of the fact that Otto Henry donated his own magnificent library of 3500 volumes to this new College. It was officially dedicated on January 19, 1559 and opened with an enrollment of 60 students.

Trouble!←⤒🔗

Just as Frederick II did not live to see Protestantism consolidated in his realm, so Otto Henry did not live long enough to see the fruits of his College. A few weeks after its opening on February 12, 1559, he died. Perhaps it was just as well, for the first fruits of his College were nothing but trouble. Otto Henry's experiment in ecumenicity soon floundered on the shoals of disagreement and intolerance.

What brought the matter to a head was the conflict between Dr. T. Hesshuss, a professor at the College as well as the pastor of the Church of the Holy Spirit, and W. Klebitz, a deacon in the church and a student at the College. By all accounts Hesshuss was a brilliant but very difficult man. Melanchthon had given him an enthusiastic recommendation and on that basis he had been appointed; however, Melanchthon either did not know him or chose to ignore the fact that there was a darker side to Hesshuss' personality. Beza, Calvin's successor, later referred to him rather uncharitably as "the syllogizing ass."

In any case, it soon became apparent that Hesshuss was not only a hard man to deal with, but that he also held certain high-Lutheran views on which he would brook no difference of opinion. He insisted that a napkin had to be held under the bread of the Lord's Supper for fear that a crumb might fall to the ground. He objected to the use of psalms in public worship and demanded that only Luther's hymns be sung. He banned the use of the Wurttemberg Catechism which Otto Henry had approved and ordered that Luther's Catechism be used in its place. To add insult to injury, he initiated all of these steps without bothering to seek the advice and approval of the consistory.

While these were all irritants of one form or another, it was the conflict that arose between him and William Klebitz that caused the most difficulties. Unlike Hesshuss, Klebitz's view of the Lord's Supper was Calvinistic and not Lutheran. As a student of the College he also defended Calvin's views and even wrote his thesis on the topic. The faculty approved his thesis and awarded him a bachelor's degree. All of this took place during Hesshuss' absence, and when he returned to Heidelberg he was incensed. He took to his pulpit and publicly attacked Klebitz, calling him a Zwinglian, a term of great insult and heretical implications. He raged against the College calling it "a hellish, devilish, cursed, cruel and terrible thing." Furthermore, he excommunicated Klebitz without bothering to consult the consistory.

While all of this was taking place the new Elector, Frederick III, was away at Ratisbon. On his return he immediately called the combatants to appear before him and demanded a written statement from each. Michael Diller spoke with both parties and finally announced that agreement had been reached on the basis of the amended Augsburg Confession. Nevertheless, the peace did not last. The following Sunday Hesshuss was busy administering the Lord's Supper, a celebration in which Klebitz as the deacon of the church was to assist him. When Klebitz came near the altar rail and began to administer the elements Hesshuss grabbed the cup from him and a struggle took place before the eyes of an astonished congregation.

Frederick III had had enough. On September 16, 1559, he dismissed both men. Hesshuss left for the city of Bremen. In the years to come he would find his services terminated six more times, all because of his arrogance and combativeness.5 Klebitz went to parts unknown, although tradition has it that he went armed with a letter of recommendation from the Elector.6

Needless to say, this controversy caused quite some consternation and fallout. For one thing, it gave rise to a new theory of church government called "erastianism." Thomas Erastus, secretary of the College, professor of medicine at the University and a member of the consistory, was convinced that this whole sorry affair could have been avoided if Frederick had been in control from the very beginning. If Christian rulers had the final say in the church, a healthier church life would emerge. In later years his view would gain considerable adherence, accounting for the rise of state churches.

On another score the Hesshuss-Klebitz controversy also led to two openings at the College. Hesshuss had been a professor there and after his graduation Klebitz had been made a lecturer, but now both were gone. Who would replace them? The choice was up to Frederick III.

The New Elector←⤒🔗

Up until now we have said very little about this new Elector. Who was he? What was his background? Frederick

Nevertheless, while these men and others may have awakened his interest in the Protestant cause, it was not until after his marriage to Maria van Anspach of Brandenburg, a devoted Lutheran, that he was forced to examine carefully his commitment to Rome. Under her influence and prodded by her to read the Bible and the writings of Luther, he slowly changed his loyalties and became committed to the Reformation movement. His father, John II, took this very ill of him and promptly reduced his annual income. The result was that Frederick and his family lived at Birkenfeld, near Treves, for quite some years on the borderline of poverty.7 But they persevered in the face of economic hardship, as well as personal sadness. In their twenty years at Birkenfeld they were blessed with the birth of seven children; however, two of them later died. Their eldest daughter, Alberta, died at the age of 15, and one of their sons, Herman Louis, drowned in France where he was pursuing his studies.

When his father died in 1556 Frederick III succeeded him as governor of the Upper Palatinate and lived briefly at Simmern. Three years later at the age of 44 years he was called to Heidelberg to succeed Otto Henry. On February 28, 1559, Frederick III became the new Elector of the Palatinate.8

A New Initiative←⤒🔗

It was a honour to be called to rule such an influential German state, but it was a honour that he was not allowed to ease into slowly. Upon his arrival he soon became aware that he had inherited a kingdom wracked with religious disagreement, with much ignorance about Biblical teaching and with considerable moral laxity, What to do? Frederick III first acted in the case of Hesshuss versus Klebitz. As we have related already, he made use of the good offices of Michael Diller in the hope that he could come up with a formula that would bring agreement between the two combatants. Diller felt that consensus would be achieved by using the amended Augsburg Confession. Its language on the sacrament of the Lord's Supper avoided the extreme Lutheran position with its emphasis on Christ being present "in" the bread and replaced it by stating that Christ was present "with" the bread. However, after some initial feelings that success was in the air, the agreement fell apart.9 Hesshuss denounced it and Klebitz felt compelled to react. Frederick sacked them both. A few months later Frederick asked Melanchthon for a written opinion and he advised him to lay aside all formulae and to rely solely on the Pauline expression "the communion of the body of Christ."10 Nevertheless, even that did not resolve the matter.

The next step was that a conference was held in June of 1560. John Frederick of Saxony, a son-in-law of Frederick and a committed Lutheran, brought two contentious theologians to Heidelberg called Maximillian Morlin and Johann Stossel. John's involvement in these sacramental debates, however, was more than just theological. He had been warned by his mother-in-law that Frederick was beginning to move away from the accepted Lutheran view on the Lord's Supper.11 In the public debates that followed P. Bouquin and T. Erastus defended the seven Calvinistic thesis on the Lord's Supper originally submitted by Klebitz. Morlin and Stossel promoted the Lutheran view of consubstantiation.12

The results of these debates were inconclusive to some, but not to Frederick III. He found the position argued by Bouquin to be much more Scriptural, and thus convincing.13

Early in the following year another development took place that influenced Frederick. The Lutheran princes gathered at Naumburg with the intent of coming to a united front against a resurgent Romanism, as well as healing some of the divisions in their own ranks. Thus they resolved to renew their subscription to the Augsburg Confession. But which one? The original could not be found and so they had to fall back on the printed editions. In comparing the printed editions of 1530 and 1531 the surprising discovery was made that the earliest edition was almost Roman in its phraseology. Hence the 1531 edition was taken as authoritative and signed by all the princes.14 In the meantime, the damage had been done. For Frederick came away from the Conference with a lesser degree of respect for that historic document.

Did this mean that Frederick now became a Calvinist? Publicly and privately Frederick always denied having a formal knowledge of Calvinism. He never identified himself as a Calvinist.15 Now the reasons for that would appear to be varied. On the one hand, Frederick III knew full well that an open declaration of allegiance to Calvinism in predominantly Lutheran Germany would cost him his throne and lead to much unpleasantness in his family. On the other hand, Frederick may have avoided such a designation out of a simple desire to avoid labels and to assert that it was not so much what Luther thought or Calvin taught, but what Scripture said that should determine the matter. The only camp that Frederick ever wanted to be in was the Biblical one.

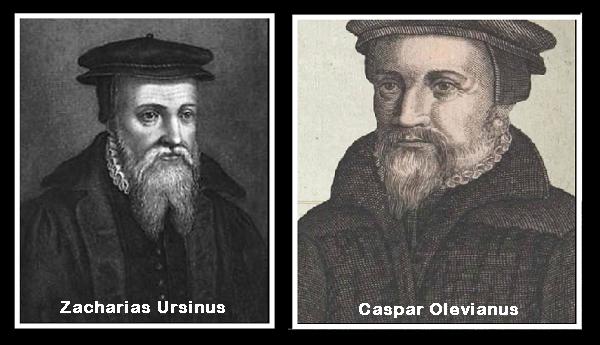

In any case, it would appear that the Hesshuss-Klebitz controversy, the conference in June of 1560, as well as other influences, all led Frederick III to the conviction that it was high time that a new catechism be written, a catechism that would be much more elaborate than the Wurttenberg Catechism, and also a catechism that would incorporate the new insights on the Lord's Supper. A formula had failed to bring unity and a conference had not achieved it either; perhaps, just perhaps, a new catechism would unite the realm and teach the people. To that end Frederick III called on two newcomers to Heidelberg: Caspar Olevianus and Zacharias Ursinus, to compose this new work.

But who were these men? Where did they come from? What kind of credentials did they have?

Caspar Olevianus←⤒🔗

Caspar Olevianus was born in Treves, not far from the border of Luxemburg, on August 10, 1536. His father was by all accounts a rather influential man: head of the bakers' guild, treasurer of the city, and a member of the city of council. Olevianus attended a number of different Roman Catholic schools and at the age of 14 years was sent to Paris to study law. It was during his stay in France that Olevianus became a convert to Protestantism. To pursue his law studies he transferred from Paris to Orleans and from there to Bourges. At Bourges he met Herman Louis, the son of Frederick III, and they became good friends. Only the friendship was soon terminated by tragedy. A group of drunken students crowded into a boat that Olevianus and Herman were using to cross a local river and it capsized. In the ensuing chaos Olevianus realized that his friend was missing. Frantically, he searched for him, but he was too late. Herman had died of drowning. With a heavy heart Olevianus wrote a letter of condolence to Frederick III.

After graduating from the law school at Bourges, Olevianus went and studied with the great leaders of the Reformation: Peter Martyr in Zurich, Theodore Beza in Lausanne, and John Calvin in Geneva. It was also during this time that William Farrell persuaded him to return to his native city of Treves and pursue the cause of reform there.

Upon his arrival in Treves Olevianus taught at an academy called The Bursa. There he laboured for one and a half years, but then on August 9, 1560, he posted notices in the city to the affect that he would be conducting a public assembly at the Bursa the next day, his 24th birthday, beginning at 8:00 a.m. The day dawned and the curious were out in force. For over two hours Olevianus addressed his audience and attacked the mass, the worship of saints, religious processions, and a host of other Roman practices. In the main church of Treves the people were taught to venerate a certain "holy coat" which the priests said had been worn by the Lord Jesus. Olevianus could not resist dismissing this as rank superstition. In his summation he urged the people to caste aside the erroneous teachings and customs of the Roman Church, and to follow the Word of God.

Olevianus' actions caused quite a stir in Treves. The city council first denied him the use of the school for these meetings, but later they gave him permission to preach in the St. James Church. From that pulpit Olevianus continued his assault on Roman doctrine and superstitions and from there as well he clarified the message of the Scriptures. The results were that Olevianus received a real hearing. Many people embraced the Protestant faith. So many in fact agreed with him that when the Elector of Treves returned from Augsburg with 170 cavalry men, the Protestants refused to open the city gates to him unless they were promised freedom of worship. The elector refused and set up his headquarters in a nearby village. From there he harassed the citizens of Treves, burning their crops, robbing its citizens, cutting off its water supply. Finally, on October 11, 1560, he stormed the city, arrested Olevianus, the mayor and twelve other prominent men who had sided with Olevianus.

For his boldness in proclaiming the Word, Olevianus found himself in prison, and there he would have remained for quite some time had it not been for the intervention of one man. Frederick III heard what had happened to Olevianus and he remembered what this young man had tried to do for his son. He sent delegates to Treves who paid 3000 Dutch guilders in order to secure the release of Olevianus. The authorities gave him eight days to leave the city and told him never to return. The Roman Catholic clergy in Treves breathed a collective sigh of relief when he departed. In addition, they organized an annual procession to be held on the first Monday after Pentecost to remember the deliverance of the city from the heresy of Olevianus, a procession still being held today.

In the meantime, Olevianus traveled to Heidelberg where he was warmly welcomed by Frederick. On December 22, 1560, he was made the pastor of the St. Peter's Church and two years later in 1562 he was appointed as the pastor of the main church in Heidelberg, the Church of the Holy Spirit. This then was one of the men who was approached to write Frederick's new catechism. But there was also another.

Zacharias Ursinus←⤒🔗

Zacharias Ursinus was born on July 18, 1534 in the German city of Breslau. Unlike the father of Olevianus, Ursinus' father was a man of meagre means and limited influence. He had changed his name from Andrew Baer to its Latin equivalent which was "ursus" or Ursinus. Not much is known of Zacharias' early life except that he was influenced by his pastor, Moibanus, a Lutheran.16 Perhaps it was through the influence of Moibanus that Ursinus came into contact with Dr. John Crato, the personal physician to the Emperor, who sent him to school and financially supported him.17

In any case, in 1550 at the age of 16, Ursinus enrolled in the University at Wittenberg. There he soon proved himself to be a very able, if quiet, student. Melanchthon, regarded by many as Luther's greatest pupil and future successor, was teaching at Wittenberg and he took this new student under his wings. Scholars debate the extent of their friendship, but that there were various ties between them cannot be doubted. Melanchthon would later take Ursinus with him to a conference at Worms. When Ursinus finally left the university in 1557 it was Melanchthon who supplied a glowing testimony to his ability.

Having completed his formal studies, Ursinus went travelling. In Switzerland, he stayed briefly at Basel and Lausanne. From there he went to Geneva and met John Calvin, who was said to be quite impressed by him and even gave him a set of books. From Geneva he went into France and visited the cities of Lyons, Orleans, and Paris. In Paris he studied French and Hebrew under Mercier and also came into contact with a number of Huguenots.

In 1558 Ursinus returned to his native city of Breslau and began a teaching career at the St. Elizabeth Gymnasium. Later he switched to the University of Breslau. All during this time, however, the Lutheran church was being torn apart by sacramental debates. The high Lutheran party, of which T. Hesshuss was but one representative, did everything within its power to repudiate the teaching of the more moderate Lutherans, led by Melanchthon. Ursinus was forced to choose sides and as might be expected he choose for Melanchthon and the moderates. He even published a small tract called Theses on the Sacraments, in which he argued for a position that bore many similarities with the Melanchthonian interpretation of the Lord's Supper.18 As could be expected this treatise of Ursinus generated reactions and not all of them were favourable. Soon Ursinus found himself embroiled in the same disputes as his mentor, Melanchthon.

By April of 1560 Ursinus had had his fill of controversy. He tendered his resignation and left Breslau.19 There are scholars who are of the opinion that Ursinus was forced to leave Breslau; however, most of the evidence seems to indicate that he simply grew tired of all the infighting. The fact that Melanchthon died on April 19, 1560, hardened his resolve not to stay in Breslau. He yearned for some tranquility.

Ursinus now headed for Zurich, where he renewed his acquaintance with Peter Martyr20 Only he did not stay there for long, because in the meantime Martyr had been informed about a teaching vacancy in Heidelberg as the result of the dismissal of Hesshuss. Martyr himself had been approached to fill that vacancy, but poor health forced him to decline. Instead he recommended that Ursinus be appointed.21 Ursinus accepted and arrived in Heidelberg in September of 1561.

A New Catechism is Written←⤒🔗

There is no record of precisely when Frederick III appointed Olevianus and Ursinus to write a new catechism. It seems that sometime in 1562 they received this charge. At the time Olevianus and Ursinus were 26 and 28 years old respectively.

There is also no record as to precisely how they worked or who did what or who wrote what parts of the catechism. Over the years many scholars have suggested that Ursinus formulated most of it in rather dogmatic language and that afterwards Olevianus came along and added the personal touch.22 There is, however, no proof for such an assertion. There is also an old tradition which states that Olevianus wrote the first draft, but that, too, has no basis. There is still another school of thought of a more modern origin which has tried to prove that in actual fact Olevianus had nothing to do with the writing of the catechism at all.23 Such an assertion would appear to go too far in the other direction. Finally, there are also historians who claim that the catechism is not so much the work of two men but instead the product of a whole committee.24 This suggestion, too, is interesting, but it is also conjectural.

What we must say is that while there is no absolute proof available that Olevianus and Ursinus wrote the catechism, there are all kinds of indirect indications, as well as circumstantial evidence, which proves this to be the case. Of the two it has to be said that there appears to be the least doubt when it comes to Ursinus's involvement. By 1562 he had written his Major Catechism and Minor Catechism. The former consisted of 323 questions and answers and was meant to be used for teaching purposes.25 The latter contained 108 questions and answers and was intended for more popular consumption, meaning the instruction of children and people in the church. It is especially in the Minor Catechism that one can trace certain similarities to the Heidelberg Catechism. It had that three-fold division of sin, salvation, and service.26 It also contained phrases, expressions and whole sentences that reappear in the Heidelberg Catechism. The evidence would thus seem to suggest that Ursinus's Minor Catechism acted as a draft.

Still, while the involvement of Ursinus in this product seems to be a certainty, and the involvement of Olevianus remains more clouded, there is no doubt that the Heidelberg Catechism was presented to the world as the work of a committee which included men of divergent theological views.27 This was done especially for political reasons. It would make it difficult for these men not to support it later. It also eliminated the criticism that the work was Zwinglian, Calvinist, or worse. Finally, it stressed the unity of the Elector's reformation.

In order to add emphasis to this aspect of unity (once the final draft of the Catechism was ready), Frederick

Mixed Reviews←⤒🔗

Once the Heidelberg Catechism was released to the public it did not take long before the reactions flooded in. On the one side, there were many favourable comments. Bullinger, the Swiss reformer, was enthusiastic and wrote,

The composition of this book is clear and its content is pure truth. All is very understandable, pious, fruitful; in concise brevity it contains a fullness of the most important doctrines. I consider it to be the best catechism ever published. God be praised; may he crown it with his blessing. Words of high praise, indeed!

On the other side, there were also those who expressed their disapproval of this new catechism. Three of Frederick's neighbouring rulers composed a written response and sent it to the Elector. It warned him about the grave errors contained in this catechism, especially in its section on the sacraments.

We know by the grace of God that Zwinglianism and Calvinism in the article on the Lord's Supper are a seductive and damned error, directly contradicting the holy divine Scriptures, the true apostolic Church, the Christian sense of the Augsburg Confession, and the generally accepted and defended Peace of Augsburg.

To say the least, weighty charges were being made against Frederick and his catechism.

In an effort to promote peace and understanding it was decided to hold a conference at Maulbronn in 1564 (April 11-15) where all of the charges could be discussed. The results of this gathering, however, served to appease no one. If anything the lines became more clearly drawn than ever.

In the following months the controversy continued to simmer and it was not really until the Diet of Augsburg held in 1556 that the matter was finally settled. That this meeting of the Diet was full of dangers for Frederick can not be doubted. A majority of his fellow electors were staunchly opposed to what they perceived to be his defection to Calvinism. They asserted that Frederick could no longer claim the protection of the Peace of Augsburg. His own brother, Count Richard, warned him not to attend for fear that he would be risking his life.

Nevertheless, Frederick went to Augsburg. There he immediately found that some of his fellow Protestant electors had been busy conspiring against him. He demanded a hearing at which he ably defended his position and rejected their charges. The Protestant electors debated the matter for days, but no consensus emerged. Finally, the Emperor himself decided to intervene in the matter. Goaded on by the high-Lutheran princes and by a number of Roman Catholic bishops, the Emperor read a decree in which he charged the Elector of the Palatinate with publishing a catechism out of harmony with the Augsburg Confession and with having introduced Calvinistic novelties into his realm. Furthermore, he ordered Frederick to retract these innovations, or else be placed outside the peace of Augsburg. It appeared that Frederick's enemies had triumphed and that his catechism would die a speedy death.

The Elector was stunned by this turn of events. He asked for a short period of time to collect his thoughts and make his defence. A quarter of an hour later he returned and stood before the Emperor. He was attended by his son, John Casimir who carried a Bible and the Augsburg Confession. With modesty and firmness he then proceeded to give his defence. He complained that he had been condemned unheard and that judgment had already been passed before a defence was heard. Nevertheless, he expressed his confidence in his imperial majesty and in his fairness. He then went on to say.

Although I have hitherto not been able to come to a perfectly clear understanding on the precise points to which charges have been presented against me and requisitions made; yet so much I promise myself, from the reasonableness of his Imperial Majesty, that he will not commence the process by the execution of the sentence, but that he will graciously hear and weigh the defence I shall make; which, if it were required, I would be ready to make undaunted in the centre of the market place of this town. So far as matters of a religious nature are involved, I confess freely that in those things which concern the conscience, I acknowledge as Master, only Him, who is Lord of Lords and King of Kings. For the question here is not in regard to a cap of flesh, but it pertains to the soul and its salvation, for which I am indebted alone to my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and which, as his gift, I will sacredly preserve. Therefore I cannot grant your Imperial Majesty the right of standing in the place of my God and Saviour. What men understand by Calvinism I do not know. This I can say with a pure conscience that I have never read Calvin's writings. But the agreement at Frankford and the Augsburg Confession that I signed at Naumberg, together with the other princes, of whom the majority are here present, in this faith I continue firmly, on no other grounds than because I find it established in the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. Nor do I believe that any one can successfully show that I have done or received anything that stands opposed to that creed. But that my catechism, word by word, is drawn, not from human, but from divine sources, the references that stand in the margin will show. For this reason also certain theologians have in vain wearied themselves in attacking it, since it has been shown them by the open Scriptures how baseless is their opposition. What I have elsewhere publicly declared to your Majesty in a full assembly of princes; namely, that if any one of whatever age, station or class he may be, even the humblest, can teach me something better from the Holy Scriptures, I will thank him from the bottom of my heart and be readily obedient to the divine truth. This I now repeat in the presence of this assembly of the whole empire. If there be any one here among my lords and friends who will undertake it, I am prepared to hear him and here are the Scriptures at hand. Should it please your Imperial Majesty to undertake this task, I would regard it as the greatest favour and acknowledge it with suitable gratitude. With this explanation, I hope your Imperial Majesty will be satisfied, even as also your Imperial Majesty's father, the Emperor Ferdinand of blessed memory, was not willing to do violence to my conscience, however pleasant it would have been to him, had I consented to attend the popish mass at the imperial coronation at Frankford. Should contrary to my expectations, my defence and the Christian and reasonable conditions which I have proposed, not be regarded of any account, I shall comfort myself in this that my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ has promised to me and to all who believe that whatsoever we lose on earth for His name's sake, we shall receive an hundredfold in the life to come.

This address of Frederick III made a profound impression on the Diet in that it silenced and shamed his adversaries and caused one of his supporters, Augustus of Saxony, to clap Frederick on the shoulder in the presence of the Emperor and the princes and to say, "Fritz, you are more pious than all of us." Quickly Frederick's brother-in-law, Charles of Baden, turned to those electors around him and asked, "Why do we attack this prince, when he is more pious than we are?" For all intent and purpose the campaign against Frederick was collapsing. In the days ahead the Emperor would try to convict him in various ways, but he would meet with failure. The Protestant princes allied themselves behind Frederick and all attempts to discredit and depose him came to naught.

On the Friday before Whit-Sunday the Elector returned to Heidelberg and there was greeted with much joy and relief by his people. For days they had been assaulted by rumours to the affect that their prince had been deposed, even beheaded. The next day he joined the congregation of Holy Spirit Church in worship, grasped the hand of Olevianus, and publicly exhorted the people to remain faithful and steadfast.

Of course, this victory did not mean that all attacks against the catechism ceased. They continued in the years to come. And yet that did not deter an increase in the catechism's popularity. No sooner were new editions printed than they were bought up. More and more copies had to be multiplied. Word quickly spread about the beauty and the faithfulness of this confession, with the result that translations were made into many languages.31 From Heidelberg a little booklet went out into the world that would make that city famous. This Catechism would bring comfort to millions and continue throughout the centuries to instruct the youth of the church in their "only comfort in life and death."

Bibliography

- Balliet, Thomas M. "Religious Education and Catechetical Instruction." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 182.

- Bierma, Lyle D. "Olevianus and the Authorship of the Heidelberg Catechism: Another Look." The Sixteenth Century Journal 13 (1982): 17.

- Dahlmann, A.E. "The Theology of the Heidelberg Catechism." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 167.

- Good, James I, The Heidelberg Catechism in Its Newest Light. Philadelphia: Publication and Sunday School Board of the Reformed Church in the United States, 1914.

- Gooszen, M.A. De Heidelbergsche Catechismus. Leiden: Brill, 1890.

- Hinke, Wm. J. "The Origin of the Heidelberg Catechism." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 152.

- Hollweg, Walter. Neue Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Lehre des Heidelberger Katechismus. Stuttgart: Neukirchener Verslag, 1961.

- Masselink, Edward J. The Heidelberg Story. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1964.

- Richards, George W. The Heidelberg Catechism. Philadelphia: Publication and Sunday School Board of the Reformed Church in the United States, 1913.

- Richards, George W. "A Comparative Study of the Heidelberg, Luther's Smaller, and the Westminster Shorter Catechisms." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 193.

- Schaff, Philip. The Creeds of Christendom. 3 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877.

- Schotel, G.D.J. Geschiedenis van den Oorsprong, de Invoering, en de Lotgevallen van den Heidelbergschen Catechismus. Amsterdam: Kirberger, 1863.

- Spangler Kieffer, J. "An Appreciation of the Heidelberg Catechism." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 133.

- Sudhoff, Karl. C. Olevianus und Z. Urslnus, Leben und ausgewahlte Schriften. Elberfeld: R.L. Friderichs, 1857.

- The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1968 ed., S.v. "The Heidelberg Catechism," by M. Lauterburg.

- Thompson, Bard; Berkhof, Hendrikus; Schweizer, Eduard; and Hageman, Howard G. Essays on the Heidelberg Catechism. Philadelphia: United Church Press, 1963.

- Truxal, A.E. "A Symposium on the Heidelberg Catechism." The Reformed Church Review 17 (April 1913): 213.

- Ursinus, Z. Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1954.

- Van Halsema, Thea B. Three Men Came to Heidelberg. Grand Rapids: Christian Reformed Publishing House, 1963.

- Visser, Derk. Zacharias Ursinus: The Reluctant Reformer, His Life and Times. New York: United Church Press, 1983.

Add new comment