Gisbertus Voetius March 3, 1589 – November 1, 1676

Gisbertus Voetius March 3, 1589 – November 1, 1676

After Four Centuries⤒🔗

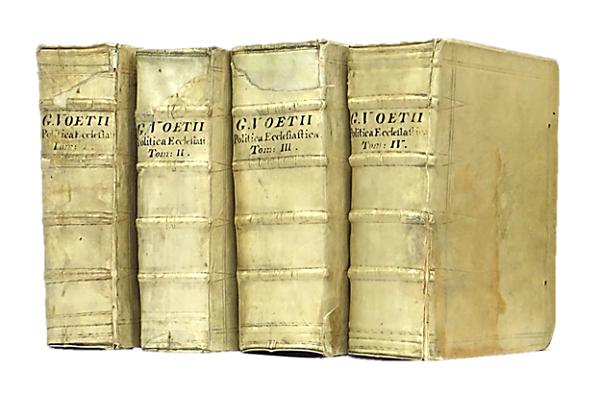

This year it is four hundred years ago that the well-known theologian, minister, professor, author, polemist Gisbertus Voetius was born. We may say that he was one of the most noted men in the Reformed churches in the Netherlands of the 17th century. After four centuries it is still worthwhile to pay attention to him. I shall give a short outline of his many-sided and many coloured life. Hereby I shall point especially to one aspect of his significance; Voetius was actually the father of Reformed Church Polity. His church-political ideas are set forth in his extensive book of four volumes, Politica Ecclesiastica (1663-1676), in which he discusses many cases theoretically as well as practically, all of them related to church life. Often there is the claim from several, even opposite sides that one is in the line of Voetius. Therefore, it is interesting and worthwhile to delve into this subject. But first of all his life and work in general should have our attention.

Life←⤒🔗

Gijsbert Voet (most of the time he is referred to by his Latin name Gisbertus Voetius) was born on the 3rd of March, 1589 in Heusden. His father was a knight, named Paul Voet. When Gijsbert was a boy of eight, his father was killed in the war against Spain. So his mother became a widow with four children, of whom the oldest one was just eleven years old. Her circumstances were very difficult, so that other families had to help her; they did, and made it also possible that the young Gijsbert could continue his studies.

At the age of fifteen he was sent to the State College of Leyden and afterwards to the University of that City. He distinguished himself by his industry and excellent memory, and profited greatly from the teachings of, among others, Gomarus and Arminius; especially the former had a great influence on the mind of young Gijsbert. At the early age of twenty-two he was already available for call and he accepted the call to Vlijmen, which congregation grew very quickly during his ministry. He declined the call to Rotterdam and accepted the one to his native town of Heusden in 1617.

Voetius preached in Heusden eight times a week. He also devoted himself to the study of Arabic and was private teacher in various branches of theology, in logic, physics, metaphysics, and in oriental languages. While only twenty-nine years old, he was delegated to the national synod of Dort 1618/1619, on behalf of the provincial synod of Zuid-Holland. He took an active part in the shaping of the formulations and decisions of the synod. In this fight against Arminianism he had had quite some experience before hand in his native town, since Arminianism flourished there as well. He also helped other churches, such as Gouda, in 1619, and later on, the church of 'sHertogenbosch. When Prince Frederick Henry of Orange besieged the latter city in 1629, Voetius was sent there on behalf of the churches of the provincial synod of Zuid-Holland, while also the classis Gorinchem appointed him as chaplain. When the city fell into the hands of the Prince, Voetius was requested to settle the ecclesiastical affairs.

In 1634 Voetius accepted the professorship of theology and oriental languages at the illustrious school of Utrecht, where he spent the rest of his life. His inaugural speech was entitled De pietate cum scientia conjungenda (that piety is to be connected with science). Three years later he served also as minister of the church at Utrecht. Voetius became doctor of theology at Groningen in 1636, Gomarus being his promoter. When in the same year the illustrious school in Utrecht was raised to the level of an academy in the same year, Voetius was appointed the first rector. He opened the academy with an address on Luke 2:46, where we read about the Lord Jesus sitting among the teachers in the temple, listening to them and asking them questions.

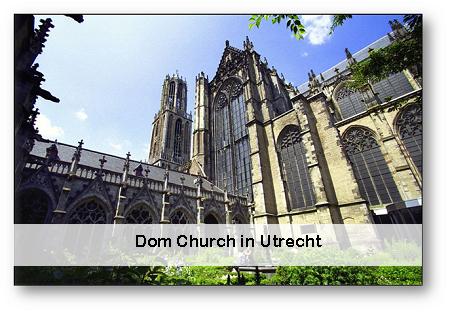

Voetius was a very busy man. He often attended the consistory meetings, gave instruction to catechism classes, gave lectures, public and private, in Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac, as well as in theology. Furthermore, he held disputations concerning numerous questions in dogmatics, ethics, philosophy and church polity. Besides, he wrote numerous books. He was a very strict and pious man, of good health and of great diligence. He usually rose at four o'clock in the morning and began his studies right away; he was busy every day for at least sixteen hours. In 1643 he bought his own house in Utrecht, in the neighbourhood of the Dome (the cathedral church). Although he received a salary of two thousand Dutch guilders (a high salary for that time) he was never rich. There are two reasons for this: Voetius was in the first place a helluo librorum (a devourer of books), and in the second place he was very generous. He was able "to give alms to all the poor and to give away all his income." Fortunately, his wife was more down-to-earth and she took care of the wages of the domestics.

It was a severe blow to Voetius that some of his children passed away in their infancy. A great blow was also that in 1672 the French troops occupied Utrecht, so that rooms of the academy functioned as storage for army provisions; the same happened with some of the church buildings. The Dome, too, fell into the hands of the Roman Catholics, and a Roman Catholic procession even marched through the streets of the city, for the first time in a hundred years. In November 1673 the French troops left Utrecht and Voetius, now 84 years of age, preached again for the first time in the Dome church on the text of Psalm 126.

Voetius became ill in 1676, and on the first of November he passed away, in the same year in which the greatest admiral of the Netherlands, Michael Adriaanszn de Ruyter died. In a certain sense Voetius, too, was an admiral. Strict and even hard on himself, he gave guidance and direction to the life of the churches. His enemies sometimes called him "Abbot Voetius," even "Pope Gisbertus" or "Papa Ultrajectinus" (Pope of Utrecht). It is true that he was not only hard on himself but also on others, being a healthy man, and very consistent, not in the least in the many controversies of his days.

Controversies←⤒🔗

Voetius was involved in many controversies during his long life. I have already mentioned the struggle against the Arminians. He considered Arminianism a deadly danger for the church, and his great ambition was the achievement of the overthrow of this heresy. He was of the opinion that the Arminian doctrines "grew rank as a cancer in the sound words of Christ."

Voetius also fought against another form of contemporary humanism, namely, the humanism of Erasmus, whom he called an Arian, Pelagian, and Socinian. And he fought against the Roman Catholics, for he saw in the Pope of Rome the antichrist. Moreover, he directed a very violent campaign against the Cartesian philosophy, first against two professors of Utrecht, then also against Rene Descartes himself.

Another important point in the career of Voetius was his conflict with Coccejus and his foederal theology. The church-historian S.D. van Veen wrote with respect to this conflict,

The more liberal tendencies of Coccejus combined with an exegesis of greater independence and a relative depreciation of practical Christianity aroused the wrath of Voetius. The resulting controversy racked the Dutch Reformed Church till long after the death of the two protagonists.

Voetius must be considered in the framework and against the background of his time. This explains how he, on the one hand, wrote his books in a scholastic way, and how he, on the other hand, propagated the pietistic revival ("nadere reformatie"). He felt much sympathy for the English and Scottish pietists and therefore he once travelled to England, in order to meet some of them. Also the pietist Anna Maria van Schuurman was among his friends. But when she went more and more in the direction of separation, together with Jean de Labadie, this friendship came to an end. Voetius then prepared a disputation concerning the separations and deviations from the churches ("Over de Scheydingen en afwijckingen van de kercken").

Voetius disputed also with Maresius, who was born in France and who became the successor of Gomarus in Groningen while he was also the minister of the Walloon church there. Maresius attacked Voetius' severe Puritanism. This conflict ended in 1669 when both of them promised to defend the pure doctrine.

Voetius' disputations were numerous. Like the puritan ministers in Scotland, he strongly opposed the right of patronage. Patronage meant that someone who had built a church building or was the owner of it had the right to appoint the office-bearers. He wrote also a disputation against Constantijn Huygens about the accompaniment of singing in the worship services by the organ. Huygens had defended the use of organs, but Voetius who was himself able to play the organ, called the playing of organs during the worship services "an iniquity."

Church Polity←⤒🔗

Voetius was of great importance, especially with respect to church polity. It is incomprehensible how one can write a biography about Voetius (as the Netherlands-Reformed Dr. C. Steenblok did in 1942, G. Voetius, His life and works), without saying a word about Voetius and Reformed Church Polity. To a certain extent we can call Voetius "the father of Reformed Church Polity," namely; in as far as he worked out the points which were accepted in the beginning of the confederation of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands. Voetius' church-political ideas are set forth in his extensive book of four volumes, Politics Ecclesiastica. He himself said that not only the articles of the Church Order of Dort, but also especially the liturgical writings formed the basis of his Politica Ecclesiastica. In the first volume Voetius wrote about the science of Church Polity as such, its nature, sources, divisions, and means. Then he describes the visible organized church, the authority and the government of the churches, but also the liturgical forms and the ceremonies, prayers, salutation and benediction, singing, reading, and preaching, baptism, Lord's Supper, Catechism teaching, and days of fasting and prayer.

The second volume (actually part two of volume 1), deals with engagement, marriage and divorce, as well as burials and so-called holy acts, freedom of conscience, church properties, etc. In both parts of volume 1 ecclesiastical matters are discussed, in the next volume ecclesiastical persons are dealt with: members of the congregation, martyrs of faith, women in the church, the office of the minister, his calling, the training for the ministry, the hierarchy in the church, and monasteries and monks. In the last volume church discipline is discussed, the confessions, ecclesiastical exams, archives, institution and planting of churches, separated and reunited churches, private and public disputes, reconciliation, and excommunication.

I have only mentioned here the main points. Sometimes Voetius appears to go in the direction of casuistry. Nevertheless, he produced impressive work and many practical questions are answered in a clear way.

Resource for Others←⤒🔗

It is no wonder that Voetius' Politica Ecclesiastica functioned as a resource for many generations after him. It is not strange either that the "father of the Doleantie Church Polity," F.L. Rutgers, together with P.J. Hoedemaker, edited selected treatises in two parts, published at Amsterdam in 1885/86. They were followed by A. Kuyper, who in 1891 edited and published the two volumes of Voetius' teaching on the Heidelberg Catechism. F.L. Rutgers very much stressed the freedom of the local church and the freedom of the believers over against what he called the second hierarchy (namely from the side of the synodical "board" of the Dutch State Church). In this regard let me mention four statements of Voetius which are very clear:

-

At the end of the first treatise, Voetius had warned that the principles of Reformed Church Polity had to be applied in such a way that everybody had to be on guard against the domination of either persons or of ecclesiastical bodies;

-

When the churches come together in major assemblies, the delegates are there not in their function as officebearers, but only as delegates of the churches;

-

Synods make decisions, but they are preceding sentences ("antecessoria"), while the churches and the members of the churches must have the right of the succeeding sentence ("subsequente");

-

If ecclesiastical assemblies make decisions which are not in accordance with the Word of God, then not their execution ("executio") but a reformation ("reformatio") must follow.

Such examples can easily be multiplied, but these are sufficient to make clear why, for instance, F.L. Rutgers so often quoted Voetius when he gave his ecclesiastical advice.

Voetius Misused←⤒🔗

In 1937 the promotion of Dr. M. Bouwman took place at the Free University of Amsterdam with a dissertation, entitled Voetius about the authority of synods. It was the last dissertation that was submitted with Dr. H.H. Kuyper as promoter. In this dissertation Dr. M. Bouwman strongly defended the right of synods to suspend and depose office-bearers. He appealed to Voetius, who was said to have stated that the whole of synodically-connected churches was an instituted church, so that one could speak of national, regional and classical churches, of which the local churches are only parts or sections. Voetius was also said to have stated that officebearers of this institution formed altogether a corpus, a corporative unity. He wrote:

According to Voetius the synod is the bigger consistory, while the local church is the smaller consistory. According to Voetius there is no essential difference between the authority of the consistory and that of the synod.

The consequence of this thinking would be that also the synods have the right and authority of church discipline.

Right away Dr. M. Bouwman was attacked from several sides, among others, by Dr. S. Greijdanus, who discussed the matter extensively in a series of eight articles in De Reformatie of April-June 1938, entitled "The Essence of the Major Assemblies according to Voetius." It is no wonder that Dr. Greijdanus opposed Dr. Bouwman. Dr. Greijdanus was a disciple of Dr. Rutgers. He had also opposed the right of the synod of Assen 1926 to depose Dr. J.G. Geelkerken. Dr. S. Greijdanus proved that Dr. Bouwman understood and translated Voetius in a wrong way and made him in fact say the opposite of what he really said. He demonstrated this with many quotations of Voetius' Politica Ecclesiastica. Sometimes, Greijdanus said, Voetius is more or less in conflict with himself, but that is in cases in which he gives an elaboration or application of principles which are completely right. Then Voetius sometimes speaks about what is, perhaps, better or safer ("melius esse," "tutius esse"). However, his principles are very clear and Greijdanus agreed completely with Voetius' statements about the major assemblies. Greijdanus also reproached the promoter, Dr. H.H. Kuyper, for apparently not being as well acquainted with Voetius as he seemed to be, and that it was strange that he let this dissertation pass.

Conclusion←⤒🔗

I conclude that Voetius was indeed an important theologian of the 17th century. We can still learn many things from him. Also what he, for instance, said about mission and the connection between mission and the church, and the planting of the church, is still relevant today, just as so many statements of his Politica Ecclesiastica. Of course, Voetius also had his weaknesses. Nevertheless, his works are still worth being studied!

Add new comment