Church and Revolution

Church and Revolution

The Secularization of Society⤒🔗

In the journalistic commentaries on the French Revolution in this bicentennial year, little attention has been given to the religious climate in pre-revolutionary France. This is surprising, in view of the nature of the event: the impact of the Revolution was felt not only in the sociopolitical, but also in the spiritual realm. Among its consequences were the destruction of the established church, a large-scale rejection of Christianity, and the inauguration of a secularized, post-Christian society.

To account for these developments one cannot refer simply to the social and political abuses in pre-revolutionary France, or even to the popularity of anti-Christian Enlightenment ideas among the revolutionaries. These factors were no doubt important, but by themselves they do not fully explain the spiritual reversal. They do not answer the question, for example, as to why the new theories became victorious, and why they led to the widespread rejection of Christianity. After all, does not the Christian message include that for which the revolutionaries were also striving: compassion, brotherhood, and social justice? Why was that message no longer proclaimed, or, if it was still proclaimed, why was it no longer listened to?

Although the French Revolution took place two centuries ago, it is still relevant to consider these questions. A study of the Revolution's background will not only teach us something about its spiritual roots – that in itself is instructive for present-day Christians – but it will also explain to us the nature of its fruits. And whatever one may say about the roots of the Revolution, its fruits are not a matter of historical interest only. They are still with us.

The Church in France←⤒🔗

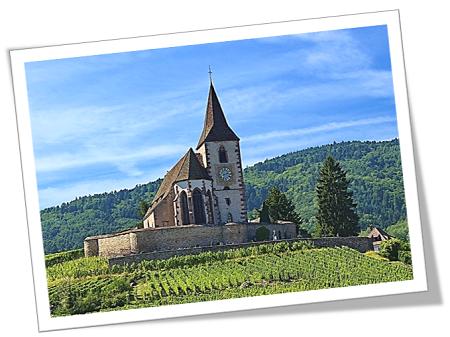

To gain an understanding of the background of the Revolution, it is necessary to consider the role of the church in eighteenth-century France. When I speak of the French church I refer to the Roman Catholic one. Roman Catholicism was the official and the only accepted religion. Deviation within the church itself, such as the Augustinian Jansenist movement, was not allowed, and Protestantism was suppressed with great severity. In 1685 Louis XIV (the antagonist of William III of the Glorious Revolution) had ended all toleration for the French Reformed or Huguenots, and in the eighteenth century that group formed a small and cruelly persecuted minority.

On the eve of the Revolution, then, the Roman Catholic Church held a monopoly position. It had also reached a very low ebb in spirituality. Secularized, oppressive, authoritarian, and very materialistic, it appeared to have few other concerns than the maintenance of its monopolistic position and the protection and increase of its vast wealth. The fact that some of the clergy, especially among the lower ranks, courageously fought against the church's secularism and tried to take their calling seriously, did not greatly change the general picture, nor did it do enough to fill the spiritual vacuum that existed in France. The people were spiritually starved and as a result had little or no defence against the anticlerical and anti-Christian ideas that were now being spread by zealous Enlightenment prophets. In other words, the secularization of society was not simply a result of the revolutionary upheaval. The process of secularization had begun, especially in the urban centers, well before the outbreak of the Revolution.

A Comparison with England←⤒🔗

This picture will get even more relief when we compare the situation in France with that of a number of other Western countries, such as, for example, England. In England also Enlightenment ideas had made important inroads, especially among the intellectuals. In fact, most of the Enlightenment theories originated in England and spread from there to France and other countries. In England, however, they did not succeed in eclipsing Christianity. To the contrary, in the age of the Enlightenment England provides us with a picture of considerable church growth and of a deepening level of spirituality among the population, not in the last place among the working classes. This happened in spite of the fact that England also had an established church which was influenced by the spirit of secularism and rationalism, and that here too all manner of dissent had long been suppressed.

Why, then, this difference? One reason was undoubtedly that the Church of England did not enjoy quite the same monopoly position as the Roman Catholic church in France, and that already at the time of the Glorious Revolution a measure of toleration was granted to most Protestant dissenters. The fruits of that toleration, introduced under William III, became evident during the eighteenth century. It was the very poverty and aridity of the Enlightenment religion in England that led to, or encouraged, various evangelical revival and reform movements. Together they had the effect of "re-Christianizing" much of England – the opposite development of what was happening in France.

Alliance of Church and State←⤒🔗

To return to the latter country: the French church's exclusivism and its secularism were not the only reasons why it was held in contempt. Also important was the fact that, with a few notable exceptions, the clergy failed to speak out against the abuses that were rampant in France, but rather helped perpetuate them. Under the old regime church and state were hand in glove, and the clergy enjoyed a privileged position. This was not a new development. For centuries already, the French church had been closely allied with the secular powers: the crown, the privileged feudal nobility, and kindred ancient institutions. Together they formed the "establishment" in pre-revolutionary France.

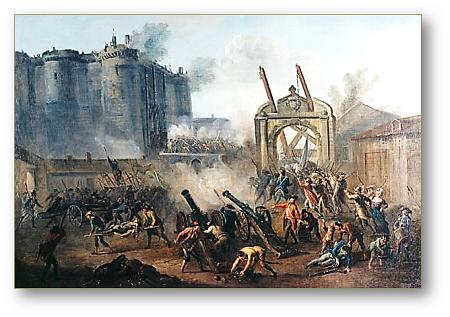

The social and financial advantages of that arrangement were considerable. Like the nobles, and in spite of its enormous landed wealth, the church itself was exempt from taxation, but it had the power to tax the rest of the population: it imposed the general church tax and it was able to exact feudal dues from the peasants living on its lands. It is not surprising that the church was seen as both part and pillar of an oppressive social system, and neither is it surprising that it shared in the fate of that system when the Revolution broke out. The French church was destroyed, together with the monarchy and the feudal aristocracy.

Revenge and Disestablishment←⤒🔗

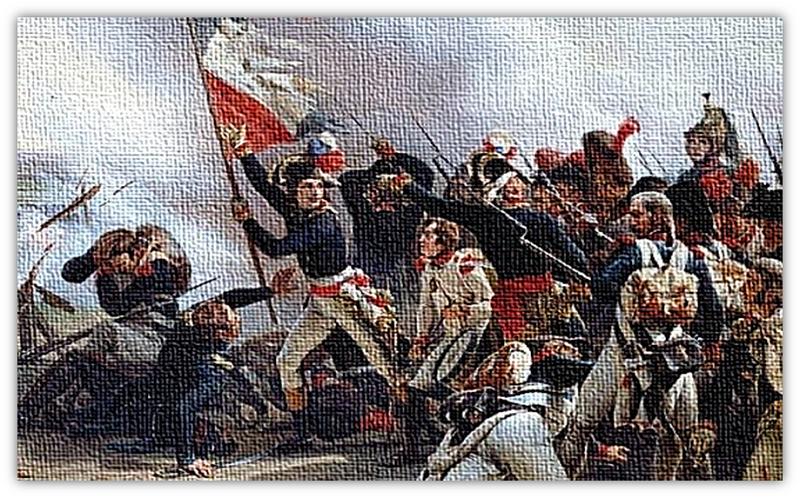

The anticlerical and anti-Christian reaction, although in its more militant phase it lasted for only a few years, was nevertheless persistent. During the first years of the Revolution monasteries were closed and church lands confiscated. At the time of the Terror a more radical process of de-Christianization started. Churches were destroyed or requisitioned, many members of the clergy and of religious orders were killed, for a time an alternative religion (that of the goddess of Reason) was instituted, and various other measures were taken to eradicate all traces of Christianity. They included the replacement of the Christian calendar with a revolutionary one, the introduction of a ten-day week, and the renaming of holidays and streets that had originally been named after Christian saints and martyrs.

After the Terror a reaction set in, and under Napoleon attempts were made to normalize the relations with the church and the papacy. The Roman Catholic church was restored, but it lost many powers to the secular government. Eventually, church and state would be separated. Under Napoleon freedom of religion to non-Roman Catholics, which had been granted earlier by a number of moderate governments, was again guaranteed. This universal freedom of religion and the disestablishment of the church are among the positive developments coming in the wake of the revolutionary upheavals. That was true not only in France, but also in other West-European countries. The measures did not, however, reverse or halt the process of secularization. It continued, and its effects, too, were felt in the rest of the western world.

The New Society←⤒🔗

When considering the fruits of this process of secularization, we can distinguish two kinds. On the one hand there was the development of the modern social and political ideologies, which were to fill the emptiness left by the rejection of Christianity. They included such pseudo-religions as revolutionary utopianism, socialism, nationalism, and whatever other -ism may have arisen in this post-Christian age, promising mankind redemption and a restoration of paradise.

These are not, however, the only fruits. The new spirit also manifests itself in ways that appear less Utopian (and are therefore perhaps less noticeable), but that are equally destructive of Christianity. Among these is what might be called the horizontalization of existence. A society built on secular foundations nourishes the belief that man has no destiny beyond the present life, and that it is therefore incumbent upon him to find fulfilment in this earthly existence. An interesting development is noticeable here. At a time when some of the pseudo-religions (such as revolutionary utopianism, and in some areas perhaps even nationalism) are declining, the striving for earthly well-being and self-fulfilment appears to be intensifying – witness the increasing demand in our days for legalized abortion and euthanasia, the new sexual morality, an increasingly hedonistic materialism, and similar social evils.

This development shows how widely the revolutionary spirit has spread: the evils mentioned in the preceding paragraph abound also in those countries that traditionally rejected the more radical revolutionary ideologies. And it underlines once again the destructiveness of this spirit. The number of abortions alone in any one of these western nations far surpasses that of all the victims of the Terror.

What conclusion is to be drawn? The background of the French Revolution (and similarly that of the later communist and fascist ones in Russia, Germany and elsewhere) teaches Christians that the church may not ally itself with the powers that be. And the nature of these revolutions shows them that in withstanding the revolutionary spirit it will not do to concentrate on its manifestations only. That is no doubt necessary, but it is not enough. The origins, the roots, also must be exposed. More than a hundred years ago Groen van Prinsterer coined the maxim, Against the Revolution, the Gospel. That message is as relevant today, in what is being called the post-revolutionary age, as it was a century or even two centuries ago.

Add new comment