Van Til and Apologetics

Van Til and Apologetics

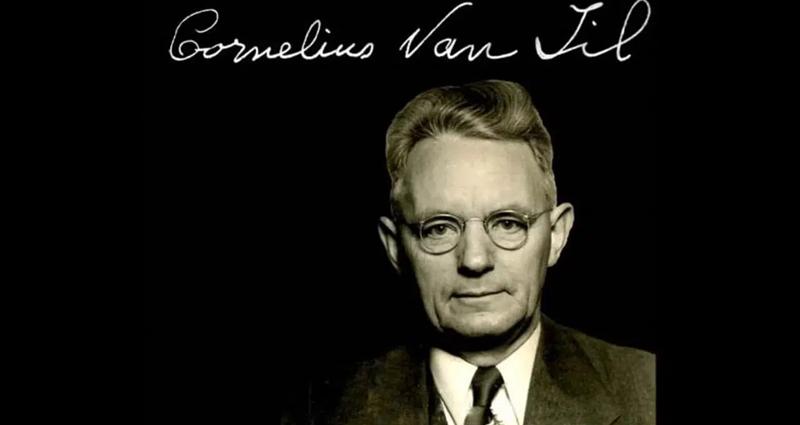

The name of Cornelius Van Til is inseparable from Reformed apologetics. Due to the importance of his thinking and of apologetics in general, I aim to provide in this brief article a few notes on his background and basic thought, as well as a summary of apologetics.

Cornelius Van Til was born on May 3, 1895, in the Netherlands, as the sixth son of godly parents. He was raised in a “lovingly strict” Calvinistic home. In 1905 the Van Til family immigrated to Highland, Indiana, to farm in a more prosperous area. They were devout members of a Christian Reformed church.

As a teenager, young Van Til felt the weighty call of God to his service. Shortly thereafter, he attended Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he immersed himself in philosophy. After receiving an A.B. from Calvin, Van Til moved to Princeton, New Jersey, for five additional years of study. He earned a Th.M. at Princeton Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. from Princeton University. His doctoral dissertation was entitled “God and the Absolute.”

After a brief pastorate at Spring Lake Church in Muskegon, Michigan (1927-28), Van Til taught apologetics for one year at Princeton Seminary (1928-29). The school's Board of Directors then elected him professor of apologetics, but he was not confirmed by the 1929 General Assembly on account of the Assembly's authorization of Princeton's reorganization along more liberal lines.

Van Til returned to Spring Lake, determined to refuse teaching at either Princeton or the newly organized Westminster Seminary, which aimed to carry on the tradition of “Old Princeton” under the able leadership of Dr. J. Gresham Machen. Nevertheless, he was prevailed upon to join the Westminster faculty by Drs. Machen and Allis, who traveled to Michigan to seek his and R. B. Kuiper's services. From the founding of Westminster Seminary in 1929 until his retirement in 1972, Dr. Van Til taught Reformed apologetics and related courses from a uniquely biblical perspective and within the confines of traditional Reformed theology. In 1936 he switched his church membership from the CRC to the newly organized Orthodox Presbyterian Church, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Van Til's thinking on Reformed apologetics, philosophy, and theology exerted a steadily growing influence on many graduate students and conservative Reformed evangelicals throughout the world. Today, his views continue to be developed by some of his students and are still frequently debated by orthodox Reformed theologians and apologists.

Van Til wrote more than twenty books during his teaching career, in addition to thirty unpublished class syllabi, which were widely circulated and are still valued. His passing away in 1987 at the ripe age of ninety-one signaled the end of an era for both Westminster Seminary and Reformed apologetics. (For additional detail on Van Til's life, see the authorized biography by William White, Jr., Van Til: Defender of the Faith, 1979.)

Theology and Philosophy⤒🔗

Two related fields of study molded the person and work of Cornelius Van Til: theology and philosophy.

-

Theologically, he was always unequivocally Reformed in principle and practice. In addition to the Scriptures, John Calvin influenced him the most during his life. The Heidelberg Catechism (via his Dutch Reformed upbringing) and the Westminster Confession and Catechisms (due to connections with conservative Presbyterianism at Princeton and Westminster) shaped his theology. Also, Van Til's theological convictions were significantly influenced by the Dutch theologians Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) and Herman Bavinck (1854-1921).

Following Kuyper, Van Til emphasized that God is absolutely sovereign over all creation, that all of life is consequently religious (whether godly or ungodly), and that all knowledge must be placed in a Christian perspective. Though Van Til often sought to rework and go beyond Kuyper and Bavinck, he never swerved from their principal thesis that,

the Christianity set forth in the Bible is the one God-revealed religion, and that Calvinism is the clearest and most consistent expression of that religion – both in content and in its life-and-world presentation.White, p. 35

-

Philosophically, Kuyper's Calvinistic principles made a major impact on the school of thought sometimes called the “Amsterdam Philosophy.” This philosophy in turn influenced Van Til, particularly in his early Westminster years. It grew out of the writings and teachings of Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977) and D. H. Th. Vollenhoven (1892-1978), brothers-in-law who taught at the Free University of Amsterdam. Dooyeweerd sought to build his philosophical system on the basis of the Christian “ground-motive” of creation, fall, and redemption.

In the last decades of his life, however, Van Til became critical of several aspects of the Amsterdam philosophy, despite his indebtedness to it. For example, he criticized Dooyeweerd for being willing to accommodate, or at least dialogue congenially with, non-Christian thinking (see the debate between Dooyeweerd and Van Til in Jerusalem and Athens, edited by Edward R. Geehan).

Apologetics←⤒🔗

Against this background, Van Til developed his “new apologetic,” in which he defends “old truth.” Though preeminently a preacher of the Word, Van Til became known primarily through his pioneer work in the field of apologetics.

Apologetics is a branch of theology that seeks to establish an effective defense of Christianity against any attack from non-Christians. Van Til himself defined it as “the vindication of the Christian philosophy of life against the various forms of the non-Christian philosophy of life.” Apologetics, p. 1.

Some well-intentioned Christians think that they are under no obligation to propound and defend their faith before a hostile world. However, this notion is not supported by Scripture. Jesus defended his claim to be the Messiah (Matthew 22), and Paul repeatedly defended his claims to be an apostle (Galatians 1, 2; 1 Corinthians 9; Acts 22-26). The classic Petrine admonition certainly implies that the Christian faith is capable of reasonable defense:

Be ready always to give an answer [i.e., a defense] to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in you with meekness and fear. 1 Peter 3:15, KJV.

The scriptural mandate is clear: the Christian faith must be defended. However, the method of apologetics that ought to be carried out has often been and still remains a matter of intense debate. Three different methods have had wide followings.

Presuppositionalism←↰⤒🔗

First, there is the presuppositional school. Its motto is “I believe in order that I may understand.” It presupposes that the supernatural revelation of God's Word provides the only basis for the entire theological enterprise. Robert Reymond succinctly states:

Group characteristics here are convictions that,

The Justification of Knowledge, p. 8

faith in God precedes understanding everything else (cf. Hebrews 11:3),

elucidation of the system [of truth] follows faith,

religious experience must be grounded in the objective Word of God and the objective work of Christ,

human depravity has rendered autonomous reason incapable of satisfactorily anchoring its truth claims to anything objectively certain, and

a special regenerating act of the Holy Spirit is indispensable for Christian faith and enlightenment.

This school is represented by the consistently Reformed tradition, including Van Til.

Van Til developed presuppositionalism along Reformed lines beyond anyone before him. Harvie Conn explains:

Van Til constructed a presuppositional apologetic based on two fundamental assertions:

Dictionary of Christianity in America, ed. by Daniel G. Reid, pp. 1211-12

the Creator-creature distinction that demands human beings presuppose the self-attesting triune God in all their thinking;

the reality that unbelievers will resist this obligation in every aspect of life and thought… Van Til opposed autonomy, the attempt to think and live by some criterion of truth other than God's Word.

Evidentialism←↰⤒🔗

Second, there is the evidentialist school, which may be represented by the motto “I understand and I believe.” Evidentialism stresses some form of natural theology as the point at which apologetics commences. As Reymond summarizes,

Group characteristics here are the following:

Justification of Knowledge, p. 9

a genuine belief in the ability and trustworthiness of human reason in its search for religious knowledge,

the effort to ground faith upon empirical and/or historically verifiable facts, and

the conviction that religious propositions must be subjected to the same kind of verification – namely, demonstration – that scientific assertions must undergo. The Thomistic Roman Catholic tradition, the (inconsistent) Reformed evidentialist traditions, and the Arminian tradition are representative of this group.

Van Til has done much pioneer work in exposing the fallacies of this methodology. He has shown that this approach fails to take into account the radical effects of the Fall, for it advocates that reason was only weakened but not crippled by the Fall. Van Til attacked two major proponents of evidentialism frequently: Thomas Aquinas, Roman Catholicism's primary medieval theologian, and Bishop Butler, an eighteenth-century Anglican. Aquinas sought for a common ground between religion and philosophy by insisting that God's existence, revealed in the Scriptures, could also be demonstrated by reason. His aim was to synthesize natural and supernatural thought, Christianity and the philosophy of Aristotle. Van Til argued that the Thomistic approach of going part way with the natural man and then leading him to supernatural truth, undermines the entire biblical structure of one system of truth. Similarly, Van Til exposed the fallacy of Bishop Butler's work, Analogy of Religion (1736), which argued for the truth of Christianity on the grounds of probability.

Experientialism←↰⤒🔗

Third, there is an apologetic called experientialism. Its motto is “I believe because it is absurd.” Experientialism stresses inward religious experience as the foundation of all theology. It accents the paradoxical character of Christian teaching to the point of asserting that Christian truth is not capable of rational analysis. Typical of this school is the Barthian tradition, which underscores the “otherness,” the transcendence, and hiddenness of God at the expense of his concrete, scriptural revelation of truth. Van Til has also done extensive work in exposing the fallacy of Barth, Barthians, and others who espouse subjective experience as independent of, or superior to, the objective character and authority of Scripture for establishing truth.

Van Til has played a major role in uncovering nonpresuppositional methods or attitudes in both non-Reformed and otherwise Reformed thinkers–particularly in the Old Princeton apologetic as advocated by Warfield and others. He has even detected signs of inconsistency in Kuyper and Bavinck. In short, Van Til has done able work in presenting a thoroughly consistent and biblical Reformed apologetic, and in purging non-Reformed apologetics from Reformed theology. He has also provided a Reformed foundation for Christian ontology, epistemology, and ethics. There is much for us to learn from Dr. Van Til, and we cannot recommend too highly his Defense of the Faith and Introduction to Systematic Theology for those who are serious about understanding Scripture and advancing in the knowledge of Reformed truth.

Add new comment