William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforcewrote in his book Real Christianity, ‘true Christians devote themselves sincerely and unreservedly to God’. I wish to show how he demonstrated this in his own life in many different ways and I hope that it will challenge you to examine your life – the way in which you live it and the way in which you try and influence society (those around you) through your commitment to Christ and the teachings of the Scripture.

Beginnings⤒🔗

On August 24th 1759 William Wilberforce was born in Hull into a highly respected family. His grandfather (also William) was known as Alderman Wilberforce. He had built a fortune in the Baltic trade and was very influential locally. Young William was the only son of Robert and Elizabeth. They were typical of the respectable classes of the time, attending church, living outwardly moral lives but there is no evidence that they were genuine believers. In 1768, Robert died, and a year later Elizabeth developed ‘a most long and dangerous fever’. So it was decided that ten year old William would go to his Uncle William and Aunt Hannah in London. He remained there for two years and he later wrote that their love touched him greatly: ‘I loved them as if they had been my parents’.

They introduced young William to evangelical Christianity. They admired George Whitefield’s preaching and kept up friendly connections with the early Methodists. He met John Newton who conducted ‘parlour preaching’ to assembled guests in the Wilberforce home. This evangelical influence on William alarmed his mother. Like most people in her social circle, she distrusted Methodists. Alderman Wilberforce issued a severe ultimatum: ‘If Billy turns Methodist he shall not have a sixpence of mine’. Elizabeth hotfooted it to London to bring him back to Hull, much to William’s distress. With his aunt and uncle he had known love and affection. Once back in Hull Elizabeth sought to scrub his soul clean of Methodism. His Methodism proved surprisingly tenacious, but so did his mother. Years later Wilberforce wrote:

My religious impressions continued after my return to Hull, but no pains were spared to stifle them… no pious parent ever laboured more to impress a beloved child with … religion than was done to give me a taste for the world and its diversions. At first all this was distasteful to me, but by degrees I acquired a relish for it, and so the good seed was gradually smothered, and I became as thoughtless as any.

William was very talented. His mind was lively and he proved to be a gifted singer and writer. At 16 he entered Cambridge. His mother had achieved her goal – God was nothing to him. He gave precious little time to his studies. His student days were filled with playing cards, singing, drinking, instrumental music and hosting dinners. His friendliness and hospitality made him very popular.

Following his education Wilberforce was expected to join the family business. During 1779-80 he developed an ardent interest in politics. This arose through his friendship with William Pitt, son of the Earl of Chatham. He and Wilberforce spent many hours together listening to debates in the House of Commons. Hot on the agenda was the American Revolutionary War. They were captivated by the oratory and the spectacle.

Wilberforce was not interested in managing the family business. His cousin who was overseeing it was doing well and supplied Wilberforce with a healthy income from it. Wilberforce returned to Hull determined to get himself elected as a member of Parliament. His charm and his purse supplemented by an ox roast for the whole town enabled him to beat both his opponents.

William Pitt was also elected to the Commons and their friendship continued to grow. Pitt had a very highly disciplined intellect and a great capacity to argue. Wilberforce on the other hand was a superb orator, the foremost public speaker of his generation. Together they were a formidable team who terrorised the government and grew in influence even though still in their twenties. Looking back, Wilberforce remarked that,

I can never review but with humiliation and shame the course I ran at college and … the first years of my parliamentary life which immediately succeeded it. I did nothing to any good purpose; my own distinction was my darling object.

Conversion←⤒🔗

But things began to change. His conversion took place gradually from October 1784 to Easter 1786.

The story began simply enough. Planning a continental tour he invited his former tutor Isaac Milner to accompany him, unaware that Milner had been converted since his previous contact with him. In the early days of the trip he ‘let loose his sceptical opinions’ and ribbed Milner about his faith. Milner replied:

Wilberforce, I don’t pretend to be a match for you in this sort of running fire; but if you really wish to discuss them in a serious manner, I shall be most happy to enter on them with you.

Confident of poking holes in Milner’s religious views, he agreed. He soon discovered he had more on his hands than he bargained for. Milner explained true Christianity to Wilberforce with fervour and compassion and backed up all he said from Scripture. The two of them studied the Greek New Testament together and Milner opened up its truths.

Returning home in October 1785, Wilberforce struggled with what it meant to embrace the Christian life. He wrote in his diary – ‘The deep guilt of my past life forced itself upon me in the strongest colours, and I [stand] condemned for having wasted my precious time, and opportunities, and talents’. He longed to find peace with God, and now knew that it could only come through Christ.

His mind was in turmoil – ‘What madness is the course I am pursuing. I believe all the great truths of the Christian religion, but I am not acting as though I did. Should I die in this state I must go to a place of misery’. Reflections like this led him to deep and earnest prayer, during which times he was brought under strong conviction of sin.

In desperation he wrote to John Newton and a meeting was arranged. Nervously Wilberforce walked around the square near Newton’s house eventually summoning up the courage to knock. Newton confided that for many years, he had been fervently praying for him. ‘When I came away’, Wilberforce wrote in his diary, ‘my mind was in a calm and tranquil state, more humbled, looking more devoutly up to God’. He had been converted.

Strange reports now began to circulate. Wilberforce was said to be out of his mind and ‘melancholy mad’. He wrote to his friend Pitt, now Prime Minister, telling him what had happened: ‘although I should ever feel the greatest regard and affection for him, and should in general be able to support his measures, I could no longer act as a party man’. He would vote with his conscience regardless of the party whip.

Having been converted Wilberforce looked around with new insight at the society in which he lived. What did he see? For the wealthy like Wilberforce life was good; entertainments included the theatre, gambling, and women. For the poor, times were tough. Even children worked long hours. For petty crimes such as stealing a scarf to keep warm, a child was executed. Hanging was a public entertainment for which people paid for the best seats. And on top of all this was slavery.

Writing in his journal on 28th October 1787, Wilberforce now aged 28 wrote: ‘God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners’.

Slave Trade←⤒🔗

The horrors of this practice are beyond our comprehension. With tightly packed loads of human cargo that stank and carried both infectious disease and death, the ships would travel across the Atlantic on a miserable voyage lasting at least five weeks. The terrible Middle Passage has come to represent the ultimate in human misery.

Many of the Africans taken aboard the slave ships did not live to see the shores of North America. It is difficult to know how many people were involved. Most studies agree that as many Africans died on the voyage as reached America – many, many million victims.

This is the horror that Wilberforce set about to overcome. As he began to look into the subject he was appalled by what he discovered. He told the House, graciously including himself in the crime:

I mean not to accuse anyone but to take the shame upon myself in common indeed with the whole Parliament for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty … I confess to you so enormous so dreadful so irremediable did its wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for abolition … Let the consequences be what they would.

The consequences would indeed be great for Wilberforce. The slave trade was big business and incredibly profitable for the traders. He faced a great deal of opposition, and the strain nearly killed him. He was so ill his opponents began to prepare for a by-election for his seat, but he recovered and on 11th May 1789 he addressed the House on the need for abolition.

He based his arguments upon ‘The dictates of his conscience, the principles of justice, the laws of religion, and of God’. ‘This house’, he declared, ‘must decide, and must justify to all the world, and to their own consciences, the morality and principles of their decision’.

How would the Commons respond?

What did the Commons do with the Slave Bill in 1789? They wanted more evidence. More years of tireless effort. More passionate speeches from Wilberforce and Pitt, but no victory.

In 1796 the motion passed the first two readings. Then came the all-important third reading. Wilberforce’s diary entry says it all – ‘March 15. Dined before House. Slave Bill thrown out by 74 votes to 70, ten or twelve of those who had supported me [were] about in the country, or [away] on pleasure. Enough [were] at the opera to have carried it’. His opponents had given free opera tickets to those they knew would support the Bill.

Devastated, stressed into ill health and weary, Wilberforce wrote to John Newton stating that he was considering retiring from public life. Newton’s reply bears a long quotation: ‘It is [not] possible at present to calculate all the advantages that may result from your having a seat in the House at such a time as this. The example, and even the presence of a consistent character, may have a powerful, though unobserved, effect upon others. You are not only a representative for Yorkshire, you have the far greater honour of being a representative for the Lord in a place where many know Him not, and an opportunity of showing them what are the genuine fruits of that religion which you are known to profess.

Though you have not, as yet, fully succeeded in your persevering endeavours to abolish the slave trade, the business is still in [process]; and since you took it in hand, the condition of the slaves in our islands has undoubtedly been already [improved].

It is true that you live in the midst of difficulties and snares, and you need a double guard of watchfulness and prayer. But since you know both your need of help, and where to look for it, I may say to you as Darius to Daniel – Thy God whom thou servest continually is able to preserve and deliver you. Daniel likewise was a public man, and in critical circumstances; but he trusted in the Lord; was faithful in his department, and therefore though he had enemies, they could not prevail against him.

Indeed the great point for our comfort in life is to have a well-grounded persuasion that we are where, all things considered, we ought to be. Then it is no great matter whether we are in public or in private life, in a city or a village, in a palace or a cottage. The promise, My grace is sufficient for thee, is necessary to support us in the smoothest scenes, and is equally able to support us in the most difficult. Happy the man who has a deep impression of our Lord’s words, Without me you can do nothing… May the Lord bless you … may He be your sun and your shield, and fill you with all joy and peace in believing.

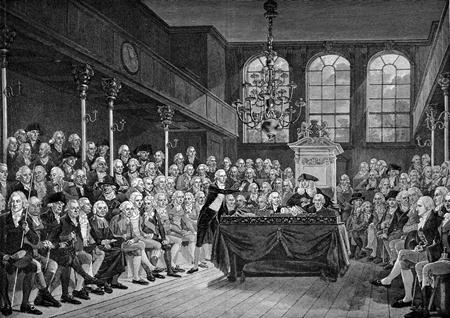

Newton’s letter helped Wilberforce to see that he needed to stay the course. Eleven long years lay ahead, but he had come through his crowded hour. Every year he suffered setbacks with defeats and deferrals. In January 1806 Pitt the Younger died. Wilberforce had lost one of his closest friends. One year later, 23rd February 1807 was one of the most significant nights in British political history. The motion was once more debated and speaker after speaker stood in favour of abolition. As they rose to their feet, head in his hands Wilberforce wept. At 4am the vote came – 283 for, 16 against. The slave trade was abolished.

Reformation of Society←⤒🔗

The ‘reformation of manners’ was the second objective that Wilberforce had committed to his diary twenty years before. He had himself undergone a great change, and his commitment to Christ showed him what his duties were to God and to his fellow citizens: ‘to promote the happiness [that is wellbeing] of his fellow creatures to the utmost of his power’. Wilberforce believed that if he did all that he could to help others come to faith the ripple effect would spread throughout the kingdom. One by one, more of his countrymen would have the hope of heaven in their hearts. They would also be taught by their faith how to show, in practical terms, that they had the welfare of others close to heart. The love of God would best teach them how they could demonstrate their love to fellow human beings.

Wilberforce therefore did three things (alongside his work on slavery):

-

Established the Society for the Reformation of Manners.

-

Worked to introduce sound doctrine into educational establishments.

-

He wrote his book, Real Christianity.

The Society for the Reformation of Manners←⤒🔗

Wilberforce had seen at first hand the havoc gambling could cause. Fornication, adultery, dueling, bribery and corrupt practices were common. The poor who flooded to the factories suffered from dangerous working conditions, overcrowding and squalor; cheap gin was poisoning people. The church was plagued by immorality and apathy, and mere nominal belief in the Bible was commonplace. Many of the clergy preferred hunting and card playing. High, middle or lower classes – it made no difference – there were crying needs to be met throughout the kingdom. Wilberforce worked for change. He was involved in organisations like the Bible Society and the Church Missionary Society which distributed the Bible and encouraged evangelism. Schools for the deaf and the blind were established. So too were lending libraries, trade schools and colleges. Public health initiatives were undertaken such as the promotion of smallpox vaccination. On top of this Wilberforce distributed his money to individuals. He visited prisons with Elizabeth Fry. He secured the release of many imprisoned for debt. He visited the sick and he funded hospitals. In order to do this he economised in his personal life wherever he could. His was a life devoted to others.

Sound Doctrine←⤒🔗

In 1825 the Mechanics Institute and London University were founded. Wilberforce wanted to establish a seat of Christian instruction and learning. He wanted courses in Christian apologetics. He wanted students to understand the Christian faith and to halt the spread of unbelief. The response from the universities was all too familiar to our ears. ‘Instruction in religion was incompatible with the first principle of receiving alike men of all faiths or of none’. Wilberforce was robust in his response – ‘Exclusion in the name of toleration produces intolerance, as well as undereducated students’. How we have seen the truth of this in our own times! But he did not win this battle. London University agreed to incorporate in their curriculum a lecture on the evidences of Christianity but it was not compulsory and was poorly supported.

Real Christianity←⤒🔗

The full title has 24 words(!) It was published in 1797 and was a best seller. He asserts that many who preach ‘do nothing to bring the glorious work of Christ to the attention of their hearers. They are heard with little interest like the legendary tales of antiquity … dismissed from our minds until next Sunday’. Wilberforce sets out that it is only through the grace of God in granting repentance and faith that sinners can be justified before God. And it is only this salvation that leads to a true Christian life which is evidenced in ‘loving our neighbours as ourselves’. Real Christianity, he asserts, is not Sunday show; it is an entire way of life that requires diligence and study and that should affect every aspect of the Christian’s public and private life. This was what made Wilberforce act as he did. This was his motivation and his driver. It is exactly the same salvation with the same God that we enjoy.

Death←⤒🔗

William Wilberforce died at the age of 73, but not before one more great event. On 26th July 1833, the bill for the complete abolition of slavery (the law of 1807 had made the slave trade illegal) was passed by the House. The news was rushed to Wilberforce – the last word he ever received from Parliament – fifty years after he had begun the fight. The following morning he seemed to rally, but then his condition worsened. When the pain grew great he said to his son Henry:

I am in a very distressed state. Yes, Henry replied, but your feet are on the Rock.

He died at 3am on Monday 29th July 1833.

Add new comment