Why Are There Four Gospels?

Why Are There Four Gospels?

They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching...

Acts 2:42

Why are there four Gospels in the Bible, and why are they so different from each other? This question is known as the synoptic problem; especially Matthew, Mark and Luke, when arranged in a side-by-side overview (Greek: synopsis), display marked similarities, while showing numerous differences also.

Let us take one example: the baptism of Jesus in the River Jordan (Matthew 3:16-17; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:21-22; John 1:32). The same event is presented four times, each time within a different narrative framework. Matthew places the encounter of John the Baptist with Jesus at the centre; in Mark, Jesus seems to be the only person to be baptised; in Luke, by contrast, Jesus is just one of the multitude; for John, the perspective is the testimony of John the Baptist.

The voice from heaven at Jesus’ baptism, recorded in direct speech, is rendered objectively in Matthew (“This is my Son”) and subjectively in Mark and Luke (“You are my Son”). John does not record the voice from heaven at all, but we do hear it echoed in the witness of John the Baptist: “I have seen and I testify that this is the Son of God” (ch 1:34). A number of hypotheses have been advanced to explain this phenomenon. During the first centuries of the church this was not yet seen as an issue. Augustine began to sense that there might be a problem, and discussed it in his ‘On the Harmony of the Evangelists’.

Since the Enlightenment, ‘literary dependence’ has been widely proposed as a solution: the evangelists were thought to have copied material from each other. Mark, the shortest Gospel, is generally believed to have been the earliest. Matthew and Luke would then have used this as their main source.

In addition, another document – no longer in existence – is believed to have recorded only the words of Jesus, and not the story of his life. This hypothetical document is identified as Q (from the German Quelle, or source). Some have gone so far as to construct an entire Q-community around it. However, in the words of the New Testament scholar Mark Goodacre, with an allusion to John 1:18: “No-one has ever seen Q”.

No Definitive Solution⤒🔗

No single hypothesis is able to provide a definitive solution, simply because we know so little about how the Gospels came into being. Against the ‘literary dependence model’ is the argument that while the four narrative frameworks may be different, they agree most closely where they represent the actual words of Jesus himself. In addition, the similarities are greatest when they record events in which Jesus’ disciples are gathered around him.

A more attractive explanation seems to be offered by what is known as the ‘tradition hypothesis’. This approach takes its starting point in a common oral tradition.

To understand this, we need to go back to the first Christians in Jerusalem. What was their situation between Easter and Pentecost? Initially, the disciples received further instruction from the risen Lord; after his ascension they waited prayerfully for the coming of his Spirit. From Pentecost onwards, they instructed the church in Jerusalem in a form of catechesis, the “apostles’ teaching” (Acts 2:42, in Greek: hè didachè toon apostoloon). Specifically, we ought to think here of the tradition concerning the Holy Supper and the resurrection. It was not long before the disciples had to defend themselves against criticism; as a result, their instruction took on an apologetic, defensive character.

Within this context, namely the apostles’ teaching in Jerusalem, the synoptic tradition might have come into existence. Various factors would have played a part.

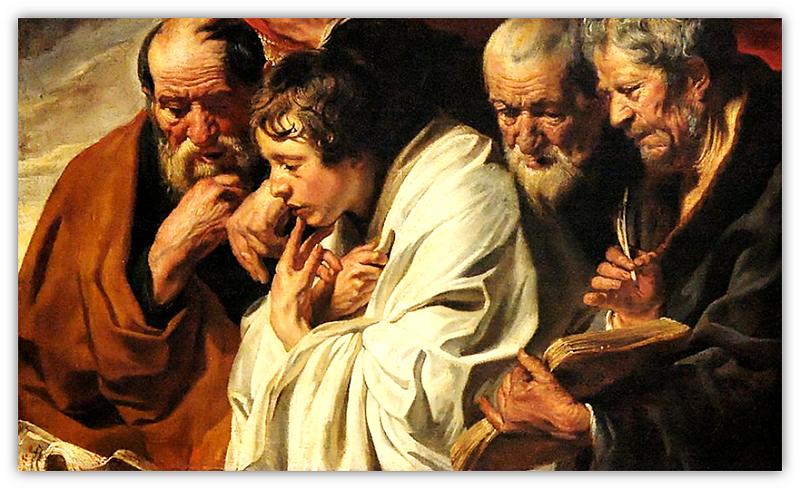

To begin with, we are dealing here with recollections. All of the evangelists, each in their own way, speak from personal experience. Matthew was one of the Twelve, Mark provides a written record of Peter’s preaching, Luke draws on eyewitness accounts, and John, Jesus’ beloved disciple, acts at certain crucial moments as a direct witness. The titles of the four Gospels, containing the names of their authors, appear in all manuscripts, and must date from the earliest period.

Doctrinal Tradition←⤒🔗

Next, there is the doctrinal tradition, which passed on what Jesus taught. The three synoptic gospels use the word didaskolos (‘teacher’) 40 times, and ‘rabbi’ 8 times, to describe Jesus. He acted as someone who taught with authority, one who was establishing a doctrinal tradition. Within oral cultures, memory training is an important means to pass on such instruction; at the same time, it is possible that some written notes were made of what Jesus said. The Gospels themselves refer to the memory of what Jesus said and did. And Jesus told the apostles to further instruct the newly converted in “all that I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:20).

Finally, the apostles were in contact with each other. During the times they met, a collective memory was formed. It was fed by their personal involvement, the activity of autobiographical memory, a sharing of information, and a concrete articulation of this tradition in spoken and written form.

Still, the Gospels were written in Greek, while the spoken version was in Aramaic. How do we make sense of that?

Of course, Jesus and his disciples were almost as at home in Greek (their second language) as they were in Aramaic (their mother tongue). In the Jewish-Christian congregation at Jerusalem there were a number of Greek-speaking believers. From its earliest beginnings, the congregation would have functioned bilingually. Thus, the apostolic proclamation took place, not just in Aramaic, but also in Greek.

Oral Tradition←⤒🔗

The word choices of Matthew and Mark, and to a certain degree those of Luke, are likely to have been influenced by these oral traditions. In addition, the Greek translation of the Old Testament is sure to have contributed to a basic Christian vocabulary, which was then further extended through the mutual relationships existing between the various churches.

The memory of what Jesus had said and done served as a kind of funnel. In this way, a collective memory took shape, shared by the apostles and other eyewitnesses; in addition, John preserved his own recollections of Jesus. This collective memory existed in both spoken and written form. Wherever possible, the preferred medium was the ‘viva vox’ (the living voice, we would say, or live transmission), but as the number of surviving eyewitnesses diminished, the need increased for written material. In the end, that led to the four Gospels as we know them.

In this process, the ‘apostles’ teaching’ served as a kind of repository and melting pot of all that had been passed on. In Jerusalem, this tradition assumed more definite forms. Sometimes, in the context of catechesis; in other cases, in an apologetic setting.

Each of the Gospels is an independent text, deriving from this shared oral source, and each Gospel is able to stand on its own feet.

From the perspective of the Christian faith, we discern another dimension of this process of remembering and proclaiming the Gospel: the work of the Holy Spirit. For in this apostolic teaching, we see a fulfilment of what Jesus, himself full of the Holy Spirit, had said to his disciples: “the Holy Spirit ... will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you” (John 14:26). Thus, the New Testament canon begins with the Gospel for four voices.

Add new comment