Reformation in Switzerland

Reformation in Switzerland

Last year, in connection with Switzerland's 700th anniversary, we announced an article on that country's foremost native reformer. We now, belatedly, honour the pledge.

Background⤒🔗

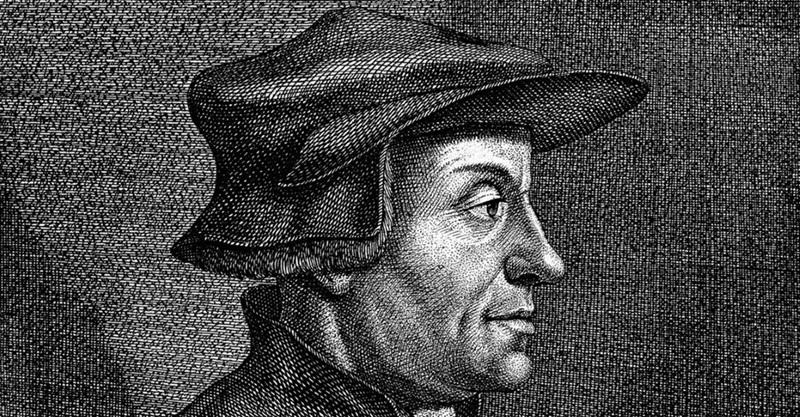

Ulrich Zwingli, the reformer of German Switzerland, was born on January 1st, 1484, less than two months after Martin Luther. A promising youth, he was given a good schooling by private tutors, and later attended the universities of Vienna and Basel. Several of his teachers were well known humanists, and at least one of them, Thomas Wyttenbach of Basel, was a reformer. It was he, Zwingli wrote later, who had instructed him “to look upon Christ as the sole price paid for the forgiveness of our sins.”

Although eventually he was to break with him, young Zwingli's real hero was the Dutchman Erasmus of Rotterdam, the “prince of the humanists.” Erasmus lived and died a Roman Catholic, but throughout his life he criticized the abuses in the Roman church, and in 1516 he would greatly help the cause of church reformation by publishing his new edition of the Greek New Testament. Luther was to make good use of this edition. So did Zwingli, who became so enthusiastic about the new version that he memorized all the Pauline epistles in the Greek original.

For a while Zwingli had considered entering a monastery so that he could develop his musical talents, but in the end he decided upon a clerical career. He does not appear to have done so because he felt any special calling to the priesthood, but merely because it seemed the logical thing to do, and also because it happened to be in accordance with his father's wishes. Some of his biographers point to this untoward beginning as an early sign of the striking differences between Zwingli and the other major reformers. These differences did exist. Luther had entered upon his career as a reformer after a long and agonizing spiritual struggle, and for Calvin the decisive factor was a profound religious experience. Zwingli, on the other hand, began his work as a humanist who, at least in the early years, showed as much interest in the study of Erasmus and of the classics as in that of the Bible.

His Road to Reformation←⤒🔗

But this attitude of indifference did not last. Chastened by illness and moral defeats, and matured by personal grief, Zwingli's religious earnestness increased. Over the years he more and more turned away from his humanistic background and toward the Word of God. It was his firm commitment to the principle of sola scriptura, and his faithful biblical preaching, especially during his years in Zurich, that would give his work lasting significance.

Zwingli had begun his clerical career in 1506, when he was 22, at Glarus. Ten years later he became people's priest at Einsiedeln. It was at this time that we find him engaged in an intensive study of the Bible and the church fathers. When on January 1, 1519 (his 35th birthday) he became people's priest at the Great Minster in Zurich he had worked out much of his reformation theology.

At this time he also discovered Luther, whose work may have encouraged him to concentrate on the preaching of the gospel in its entirety. Preachers in the Roman Catholic church were supposed to deal only with the bible passages that were prescribed in the liturgical calendar. Zwingli instead announced to his new congregation that he was going to preach through the entire gospel of Matthew, chapter by chapter and verse by verse. Having finished that gospel, he moved on to other books of the Bible, from both the New and the Old Testament.

Preaching the Word←⤒🔗

No manuscripts appear to have been left of these sermons. Zwingli never wrote them out, and although some of his listeners left notes, apparently no one ever copied down a complete sermon. The notes give a good impression, however, of both the simplicity and the directness of Zwingli's preaching style. In a sermon on Isaiah 1:17, “Defend the fatherless, plead for the widow,” he said,

These are the works which are well pleasing to God. You must cast off the burden of sin and then at once the joy of a good conscience will fill your life. If anyone bears a heavy burden and asks, “How shall I manage to dance?” he is mad. We likewise: if we bend under the weight of sin and if we try by means of ceremonies to please God, and to gain peace of conscience, we are fools.

As Jean Rilliet, Zwingli's biographer, notes, such faithful biblical preaching could not but bear fruit. At first there were no revolutionary changes in Zurich: images remained in the church, and the mass continued to be said. The people, however, learned to submit themselves to the Word of God, and this meant that the removal of traditional rituals and customs became inevitable.

One of the first reforms was the abolition of clerical celibacy. This ecclesiastical rule which forbade clergy to marry was quite universally transgressed against in the reformation period. Even popes openly maintained mistresses, and their example was followed throughout the hierarchy. Zwingli, too, admitted his guilt in this respect, and worked hard for the abolition. The town council obliged, and various priests married, including Zwingli himself. In these years Zurich also saw the replacement of the mass by the Lord's Supper, the removal of images and relics, the abolition of indulgences, pilgrimages, and various other Romanist doctrines and practices.

Zwingli and Luther: the Eucharistic controversy←⤒🔗

In this same period the reformation spread to other areas of German speaking Switzerland. By 1530 Bern, Basel, St. Gall, Mühlhausen, and Schaffhausen had become protestant, as had the imperial city of Constance. Much of the southern part of the country, however, remained staunchly Roman Catholic. This was the area of the forest cantons which formed the ancient core of the Swiss Confederation: Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, and Luzerne.

Switzerland was being divided along religious lines, and conflicts threatened between Roman Catholic and Reformed cantons. Expecting war, the Roman Catholic cantons concluded an alliance with Switzerland's ancient enemy, the Austrian Habsburgs, whereupon the Zwinglians began to look for help in Lutheran Germany. Since the Lutherans themselves were threatened by the Habsburgs, some of their princes were in favour of an alliance with the Zwinglians. But before such an alliance could be concluded the matter of their religious disunity had to be addressed.

Luther and Zwingli disagreed on a number of points, and most seriously so in their view of the Lord's Supper. Luther had from the start repudiated the Roman Catholic teaching that in the mass the priest repeats Christ's sacrifice, and that the bread and wine change into the real body and blood of Christ (the doctrine of transubstantiation). He also opposed the Romanist idea that grace is infused, in an automatic manner, by means of the sacrament, and he constantly emphasized the necessity of faith. He did believe, however, that Christ was bodily present in the Lord's Supper, and in the course of the eucharistic controversies (first with the German radicals and then with the Zwinglians) he stressed this more and more. In the end he came with his idea of consubstantiation: the elements in the Lord's Supper did not change, but Christ's real body and blood were nevertheless present “with, in, and under” these elements of bread and wine. When he began his reformation, Zwingli had explained the Lord's Supper as primarily a memorial meal, but later he more and more stressed His spiritual presence as well. He continued to reject Luther's idea of the bodily presence, however, as well as his conviction that in the Supper the believer has true communion with Christ's humanity. Unfortunately for the sake of unity, this was done at a time when in Germany radicals like Carlstadt, the Zwickau “prophets,” and the early Anabaptists also attacked Luther's view of the real physical presence. Luther therefore associated the reformer of Zurich with his German opponents, and he and his followers made that clear in their writings. Zwingli and his supporters responded, and by the middle of the 1520s a serious battle between Lutherans and Zwinglians had erupted. It was so acrimonious that the chance of political cooperation seemed remote.

The Marburg Colloquy←⤒🔗

That an attempt was nevertheless made was a result of the threatening political situation. One of the Lutheran princes, the young Philip of Hesse, realized the urgent need of cooperation and managed to get Luther and Zwingli, with their respective supporters, together in Marburg, his capital city. Also present were representatives of a number of imperial cities in South Germany, where both Luterhanism and Zwinglianism had become influential.

Among them was Martin Bucer of Strasbourg, who would soon become the colleague and mentor of John Calvin. Bucer tried to mediate between the two antagonists. His view of the Lord's Supper was half-way between Luther's and Zwingli's and was similar to that which Calvin later taught. Both Bucer and Calvin agreed with Zwingli in rejecting Luther's idea of Christ's physical, bodily presence. At the same time they maintained, with Luther, that in the Supper believers do have true communion with Christ, also according to His humanity. Like Luther, and much more so than Zwingli, they stressed the element of mystery in the sacrament: believers indeed partake of Christ's body and blood, although in a spiritual sense and with the mouth of faith, and so, through the working of the Spirit, they are incorporated into His body, which is in heaven. A well-known example of that interpretation is found in Lord's Days 28, 29, and 30 of the Heidelberg Catechism.

The Colloquy took place in October 1529. Thanks to Philip's urgings and the mediating efforts of Bucer and others, agreement was reached on various points of doctrine. Luther refused to budge, however, on the point of the Lord's Supper and kept insisting on the literal interpretation of Christ's words “This is my body.” Melanchthon, Luther's colleague and chief adviser, appears to have counselled against any compromise. He still hoped for a reconciliation with the Roman Catholics and realized that an alliance with Zwinglianism, or even an acceptance of the Zwinglian view on the eucharist, would constitute a major stumbling block. No agreement was reached on the central issue, and no military alliance ensued. It is doubtful, in any event, whether Luther would have consented to such an alliance. He refused to believe that the sword should be used in defence of the gospel.

Civil War and Defeat←⤒🔗

On that point, too, he differed with Zwingli, who indeed too readily trusted in the power of the sword. It may have been part of his Swiss heritage: for a long time the Swiss had been in great demand, internationally, as mercenary soldiers. In Zwingli's days the popes and the French kings especially competed for them. As a young priest Zwingli himself had been in the pope's pay, and he had accompanied Swiss soldiers fighting abroad as their chaplain. When he witnessed the carnage, however, and realized the corrupting influence of this military life upon the Swiss, he had fought the custom and begged the cantons to discontinue it.

He nevertheless appears to have believed that the use of power and might on behalf of the gospel was legitimate – although it is true that he may have seen the war primarily as a defensive one. In any event, he was convinced that a clash with the forest cantons was inevitable and, believing that offence is the best defence, he urged the Council of Zurich to prepare. In 1529, before the Colloquy, protestants and Roman Catholics had already confronted each other on the battlefield of Kappel. Bloodshed was then avoided, however, because the soldiers on both sides refused to fight each other, and a peace had been concluded.

After Marburg, Zwingli continued to push for a confrontation even though Bern, Zurich's major ally, refused to go to war. At this point the forest canton's, angry because the protestants had instituted economic sanctions against them, took the initiative. In October 1531 their army of 8000 men marched against Zurich, which was unprepared and could muster less than one-fourth of that number. The army of Zurich was routed. Five hundred men fell on the battlefield. Among them were several town councillors and more than twenty ministers, including Zwingli himself, as well as his step-son, his son-in-law and two of his brothers-in-law. When the next morning Zwingli's body was found, his enemies quartered it and burned the pieces, mixed with dung, on the battlefield. Erasmus openly rejoiced in the death of his former admirer, and Luther declared that Zwingli's fate must be seen as a divine judgment, because of the Swiss reformer's heresies and because he had taken the sword on behalf of the gospel.

After the defeat Bern and other protestant cantons came to Zurich's rescue, and the Second Peace of Kappel (1531) was not as ruinous to the protestants as might have been the case otherwise. It established that each canton would decide on its own religion, but that Roman Catholic minorities were not to be disturbed in protestant lands. Protestants would not be allowed the same privilege, however, in Roman Catholic cantons, and these cantons would also control the lands that were held in common. The reformation was not allowed to spread, and Switzerland's religious division was to be perpetuated.

Reformed Unity←⤒🔗

Heinrich Bullinger succeeded Zwingli as pastor at the Great Minster. Born in 1504, he was of the generation of John Calvin, who would begin his work in Geneva five years after Zwingli's death.

Calvin desired unity with Zwinglians as well as Lutherans. The Lutherans could not be won, but Bullinger was ecumenically-minded. In 1549 a consensus was reached on the issue of the sacraments, and in 1566 Bullinger concluded with Beza (Calvin's successor) the Second Helvetic Confession.

This agreement, which united Zwinglians and Calvinists, was signed by the ministers of several cantons. Later it was also to be recognized and/or adopted by the protestant churches of Scotland, France, Hungary and (with some changes) by those of Poland. In the end Zwinglianism, which had been rejected by the Lutherans at Marburg, was to be united with the international Reformed community.

Add new comment