Paradigm Shifts – A Historical Survey

Paradigm Shifts – A Historical Survey

The terms paradigm and paradigm shift are fashionable ones. You have no doubt heard about them in all sorts of contexts. You will hear about them again, for the term paradigm is used a lot in educational theory as well.

Literally, the word paradigm means pattern or example, and traditionally it was used, for instance, in grammar, to denote a representative set of inflections. In the sense in which it is often used nowadays, however, it means something quite different. In today's parlance, paradigm frequently refers to a society's central belief system or its collective consciousness – to that intangible but important entity that we also call the prevailing world view, or the spirit of the age, or the climate of opinion of a particular society, or its Utopia. This is the meaning in which I will use the term today, although I realise that it can be applied in a much more restricted sense as well.

For our purposes, then, a paradigm is that which gives unity and cohesion to a specific culture. And a paradigm shift signifies the process whereby one such paradigm is being replaced by another – usually by something that is at least in some important ways its opposite. Such a paradigm shift, you will understand, is not a peaceful affair. To the contrary, it tends to be accompanied by much unrest and by profound dislocations of all possible kinds. We should know, for we find ourselves in the midst of such a process.

Paradigms or world views affect us in all that we do and say and think. We have to examine them therefore as intelligent human beings, and as Christians. If we don't, we run the danger of being influenced by them unconsciously. As Socrates already told us: we must know ourselves and that what moves us. Or, to say it in biblical terms: we must test the spirits. The study of paradigms is an important part of this self-examination and testing.

Keeping these goals in mind, I will describe the nature of the two paradigms that are fighting for our society's adherence in these closing years of the 20th century (and will continue to do so in centuries to come): the modern or mechanistic one, and what I shall call the post-modern or holistic one. In the process I shall also say something about the causes of the present upheaval. I intend to do all this by means of a survey of the intellectual history of our society over the past 400 or 500 years.

You may ask why such a lengthy historical approach is necessary. There are two reasons, which I would like to spell out at the beginning.

-

Firstly, I am convinced that, in order to determine the nature of succeeding world views, as well as the manner in which they affect us, it is very helpful to trace their development in history.

-

And secondly, a survey of our civilisation's paradigms will be the equivalent of a sketch of western man's search for truth and certainty, for freedom and autonomy.

All that is implied in the concept of paradigm. It deals with ultimates: with man's view of God and the world, of life and death, of meaning and destiny. It is not for nothing that people also refer to it as a society's world view or even as its utopia – its search for the lost paradise.

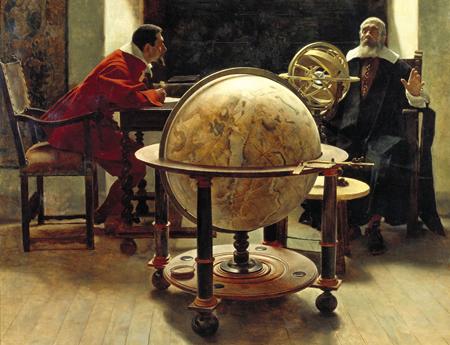

The Scientific Revolution⤒🔗

The paradigm that is being challenged in our days has been in place during most of the modern period. It has been operative ever since the scientific revolution, which ran from the middle of the 16th century to the end of die 17th, and which separates our modern period from that of the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. It is usually referred to as the mechanistic or Cartesian paradigm – Cartesian being the adjective of Descartes, and Descartes being die 17th-century French mathematician-philosopher who, with the Englishman Sir Francis Bacon, is credited with the development of the scientific method. I will come back to Descartes, and also to Bacon, but to place them in their proper context I must begin by saying something about the origin and character of the scientific revolution.

That revolution is generally said to have begun around 1543, when Copernicus's famous book on the revolutions of the heavenly bodies was published, wherein he proposed to replace the earth-centred universe by a sun-centred one. This is as good a date as any, as long as it is realised that there was more to the scientific revolution than a shift in cosmology or in models of the universe. It also signified, inter alia, a profound change in the methodology of science, in its nature and goals, and not in the last place, in the role that henceforth science would play in society.

That role would be a dominant one. In the Middle Ages science had been relatively unimportant. Far more important at that time were such disciplines as theology, philosophy, and law. After the scientific revolution, however, science would dominate culture; in time, it would become the religion of the modern age.

The question that is increasingly being asked nowadays is whether this development was as much of a derailment, an aberration, as has traditionally been assumed. When attempting to explain why our civilisation became so scientific and technological, historians often refer, among other things, to the important role played by the Christian religion in our culture. They have mentioned, for example, western society's desire to fulfil the cultural mandate, its belief in the fact that matter did not have to be shunned (as eastern religions used to believe) because Christ had redeemed it, its belief that God reveals Himself in His creation, and so on.

These factors indeed played a role. So did non-religious ones. Among these non-religious "causes" of the scientific revolution we could mention the renewed interest in Plato and in mathematics during the Renaissance, as well as the influx of Arabic learning. Also helpful were certain strains of medieval scholastic philosophy, such as nominalism. Some medieval scientists, who had already begun to stress the need of observation and experimentation, further helped prepare the soil.

Its Renaissance Roots←⤒🔗

All this ancestry is quite reputable, and it is this type of roots that scientists and historians have traditionally stressed. In recent decades, however, a school has arisen which maintains that the scientific revolution had other origins as well – less reputable ones. Although there is still some controversy on the issue, the new school has come with so much evidence that I do not believe it is possible any longer to ignore it. I will summarise its thesis for you.

That will imply a bit of a detour because it necessitates a closer look at the Renaissance, but it is worth it, for it will clarify some important points about our modern paradigm that used to be obscure. It will also suggest, I should add, that the origins of our modern world view are rather more pagan than has often been assumed.

The scientific revolution had its beginnings in the Renaissance. Usually the Renaissance is seen as a time of revival and rebirth, of sweetness and light, and in some respects that is what it was. But as historians have always known, it also had its murkier side. The Renaissance was an age (two or; three centuries in length) of transition between two well-defined cultural periods, each with its own peculiar paradigm: the Middle Ages and the Modern Age. That means that the people of the Renaissance lived through a cultural change – through a paradigm shift. And they experienced all the unrest, dislocations, uncertainties, agonies, and traumas that tend to accompany and characterise such shifts. An additional benefit of studying this period, therefore, is that it helps explain our own times. At least, it does that for me, and I hope that you too will notice parallels. Paradigm shifts, no matter when they occur, have a kind of family likeness.

The problems in western Christendom began around 1300. Generally and globally speaking, between about 1000 and 1300 western Europe had experienced a time of considerable economic expansion and cultural growth, increasing prosperity, and relative peace.

Then quite suddenly, around 1300, things change. We get a bad weather cycle, the population decreases, marginal lands return to wilderness, and in 1347 the Black Death comes to Western Europe for the first time. It wreaks terrible havoc on its first visitation; it is estimated that between one-third and one-quarter of Western Europe's population succumbs to the plague in a three-year period. And it keeps coming back at set intervals, well into the 17th century, to remind people of their mortality. Another disease hitting Western Europe for the first time is syphilis, which apparently has been brought back by Columbus's men from America. In a society where sexual mores have grown lax, it slays its thousands.

There are other dislocations. Wars become frequent, as do urban uprisings and peasants revolts. In 1453 the Turks capture Constantinople and threaten to overrun the Balkans. Hungary, and, it is feared, the rest of Christendom, and there is no Charles Martel to stop them.

Perhaps most terrifying of all, the church is now in deep decline from the papacy downward. Accompanying and aggravating all this is the fact that the philosophical underpinnings of medieval Christendom begin to give. Thomas of Aquinas's beautiful synthesis, which had reconciled reason and revelation to most people's satisfaction, comes under attack and loses the allegiance of many. All in all, the situation is bad, and it is quite generally felt that the end of the world must be near. That doomsday feeling is still present at the time of Luther, and indeed throughout much of the tumultuous 16th century.

Renaissance Occultism and Faustianism←⤒🔗

How do people react to all the physical, intellectual, and spiritual turmoil that characterised the Middle Ages? In various ways. There are the humanists, who turn toward the classics of Greece and Rome. Some become semi-pagan in the process; others, the so-called Christian humanists, concentrate on social, educational, and church reform. There are other reform movements, some of which will eventually come together in the protestant reformation of the 16th century.

Mysticism also increases, as people more and more turn away from the official church. Some of this mysticism is quite orthodox and biblical; some of it is not. Heresies abound. Even pantheistic notions surface. In addition there are hysterical religious reactions. A well-known example is that of the flagellants, who wander for days on end in processions and scourge each other until the blood flows, in order to beg God for mercy. The dance macabre or dance of death is popular in art and literature. Satanism flourishes, as does witchcraft. The inquisition works overtime, but the more witches are burned, the more turn up. Some are innocent victims; others apparently are genuine. It looks as if people, having given up on the church, seek out satan and his demons to give the protection and to provide the meaning that church and society withhold from them.

Witchcraft seems to have attracted many of the uneducated. Among the well-educated there is a growing interest in other aspects of the occult as well. Humanists study ancient writings on magic, the occult, number mysticism, and similar matters, and begin to practice them. Alchemy – including the attempt to transmute basse metals into gold, to find the philosopher's stone, and the elixir of life – flourishes. Astrology, too, becomes a major business: there is hardly a prince in Christian Europe who does not have a court astrologer to tell him or her when the times are propitious for certain exploits.

Practically all of this occult and magical business goes back to ancient sources – oriental, Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Hellenistic, and Gnostic. Unfortunately I cannot take the time to give you many concrete examples. I must give a bit of an outline, however, both to make clear the influence this occultism had on the new science, and to show the similarities with our times (New Age and all that).

Renaissance Magicians and other Occultists, Then, Believed, among other things, that←↰⤒🔗

-

the universe was a living organism

-

every part of it was intimately connected to every other part

-

there was a direct link between the microcosm (man), and the macrocosm (the universe)

-

everything in the life of man and nature was governed by the heavenly bodies – sun and moon, planet and stars

-

therefore, by studying stellar constellations, one could predict the future and select the proper moment for whatever action was contemplated

-

furthermore, the heavenly bodies were animate, had souls, and could be influenced by man, to whom they were linked

-

the spiritual beings beyond them, the angels, could similarly be influenced

-

there was a two-way traffic, therefore: man, by magical and occult means (including the conjuring up of angels) could reach upward and so gain control of both the earth and the heavens.

Mathematics and numerology provided one way of doing this. I am mentioning this because this kind of magic was also practised by reputable mathematicians, who would also contribute to the development of normal science. These practitioners believed that the universe could be divided into three realms: the natural one, where the magus operates with natural magic; the middle celestial world where he operates with mathematics, and the supercelestial world where he operates with mystical numerology (which came originally from Jewish and Egyptian sources), and where he reaches the One, God. A certain Dr. Dee in England, a well-known scientist, mathematician, geographer, astronomer, and patron of the Elizabethan literary Renaissance, who also happened to be the court astrologer of Queen Elizabeth, was quite fascinated by this type of magic. So was the Queen and her circle.

These, then, are a few examples of the kinds of occultism that flourished during the Renaissance, In a moment I will come to the question how all these beliefs and activities influenced science. First something has to be said about the why of this occult revival. One reason was no doubt the decline of the church, the secularization of society, and people's consequent hunger for the spiritual. We notice throughout history, and also again in our own days with the rise of the New Age movement, that when a people loses its faith in God, it turns to idols and to the occult. It happened already in biblical times. Note how often the people of Israel were tempted to follow nature and fertility religions such as the worship of Baal and Astharte, to adore the hosts of heaven and make sacrifices to the queen of heaven, to worship the sun, and so on. Note also how very seriously the LORD took especially these instances of apostasy.

This search for occult powers, also in our own history, is often done with the greater determination in a time when despair is mounting and doomsday feelings are widespread. Salvation must be had. If it cannot be found with the established church, as was the case during the Renaissance, then it is always possible to make an appeal to paganism and its occult and magical practices. But once the process has begun, it is difficult to stop. The search then is not only for spiritual salvation, but also, and increasingly so, for control. Control of the universe and, if possible, control of heaven itself. This happened in the Renaissance. And not just among atheists; some Renaissance figures, including Dr. Dee and several of his colleagues, tried to combine this occultism with orthodox Christianity. There were also others, who openly departed from Christianity for the sake of occult power.

This desire for power at all costs is sometimes called Faustianism, a term that in fact comes from the Renaissance. It originated in Germany and goes back to a historical Faust, who died around 1540. He pretended to be a humanist and medical doctor, but in reality seems to have been a practitioner of black magic, who was said to have made a habit of conjuring up demons. His story, which by then already had developed into some kind of legend, was first published in 1587. The English Renaissance writer Christopher Marlowe used it for his play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. Like all Fausts, Marlowe's was dominated by a ruling passion: the yearning for forbidden knowledge and power, which caused him to sell his soul to the devil and … led to his destruction. Having conjured up Mephistopheles himself by means of his black magic, he was, in the end, dragged down by him to hell.

The Occult and Modern Science←⤒🔗

This Faustian theme reappeared in the Romantic period. Goethe wrote a tragedy about Faust. Mary Shelley also referred to the theme in her Frankenstein. The Renaissance and Romantic Faust has become the symbol of western man in his quest for power, certainty, and autonomy – apart from God, and at the cost of, his soul. It is part of the modern, mechanistic paradigm. I am afraid that it is part of the post-modern, holistic one as well – certainly if the New Age movement gains more influence.

It is in this type of society, then, that the scientific revolution has its beginnings. The obvious question is: did the new science in its childhood stay clear of these occult and Faustian influences? And the answer is: apparently not – at least according to the historiographical school I mentioned at the beginning. In fact, it has been conclusively shown that several 16th and 17th-century scientists combined an interest in the occult with one in science proper. Among them are John Dee (whom we already met), Sir Francis Bacon, Kepler, and even Sir Isaac Newton. According to his unpublished papers, Newton attached as much importance to his studies in alchemy as to his mathematical achievements.

Bacon and various others outgrew the addiction. Some, again including Bacon, became shining examples of scientific rectitude who spent the rest of their lives fighting the influence of Renaissance occultism. As time wore on, that tradition was more and more becoming an embarrassment. This was especially the case in the 17th century, with its authoritarianism, hatred of heresy, and fear of unrest. But what remained of the occult tradition, also when that tradition itself had been forsworn and successfully suppressed, was the desire for power and control, and the eagerness to manipulate and master nature. Both the professed goals and the terminology used by the new scientists betray the kinship.

To realize this, you must remember that most earlier scientists, beginning with the Greeks, had been motivated primarily by intellectual curiosity. They were rarely thinking of applied science, with its implications of controlling and exploiting nature. Sir Francis Bacon was one of the men who set the tone for the new science by stressing exactly those aspects. One of his famous slogans was that knowledge is power, and equally well-known is his use of such phrases as "putting nature to the torture" in order to wrest her secrets from her.

Occultism influenced science in other, subtler ways. The faith in the magical function of numbers, for example, undoubtedly strengthened the belief that one way of penetrating the secrets of the cosmos was by means of mathematics. Furthermore, as some historians have suggested, Renaissance Neoplatonism, combined with a revived Gnosticism, probably helped convince the people of the time that the way to perfection lies in knowledge, rather than in faith. That same Neoplatonism will have provided a basis for the belief that the human mind can indeed penetrate the universe, and also for the idea, which was later validated by Kepler, Galileo, and Newton, that the earthly and heavenly realms are of the same substance, and subject to the same laws. Neoplatonism removed the sharp division between heaven and earth that had characterized the medieval, Ptolemaic cosmological model long before the scientists did so.

One more point, before I move on to Descartes. Ever since our infatuation with science and technology has turned sour, people have been looking for scapegoats on whom to blame the problems associated with modern science and technology. According to many, following the well-known historian of science Lynn White, Jr., the blame goes squarely to Christianity. New Agers have taken up the cry. As we saw, the Christian religion indeed influenced the development of science. The foregoing should have shown, however, that there are other explanations for the abuses that the scientific revolution brought in its wake.

This is not to say that Christians have not often too readily accommodated themselves to the prevailing paradigm. What we must object against is the imputation that the present predicament is a result of Christian doctrine, and of obedience in the fulfilment of the cultural mandate. The Bible does not encourage the exploitation of the environment. Old Testament laws, instead, stress careful management and conservation. Furthermore, the Bible tells us that creation was given to man not for his own aggrandizement, but in order that he might serve his God. The opposite happened in the modern period, and it is this idolatry that lies at the root of the problems facing our society.

Rise of the Mechanistic Paradigm←⤒🔗

But to get back to our topic. From Bacon it is but one step to Rene Descartes, the father of the mechanistic paradigm. I mention Bacon and Descartes in one breath because, as I said earlier, they are credited with developing the scientific method. Bacon, who died in 1626, was the empiricist, who emphasized observation and experimentation. His younger contemporary Descartes realized that pure empiricism won't do, because our senses often deceive us. He stressed mathematics and logic. He is the rationalist par excellence, which means that for him the one and only road to truth is the human mind. You probably remember him as the man who came up with the maxim Cogito ergo sum – I think, therefore I am.

For Descartes, man's essence is that he is a thinking being. The human mind decides absolutely everything, even the existence of God, and what the mind cannot conceive or prove, does not exist. This led to the rationalistic reductionism, one of the major creeds of the modern, post-Christian age. And it set the tone for the Age of Reason or the Enlightenment, as the 18th century would be called.

Descartes' fertile brain came with other seminal ideas. He insisted on the essential difference – the absolute discontinuity – between mind and body, and between mind and matter in general, and so introduced what became known as Cartesian dualism. His world view was not only dualistic, but also mechanistic. For him just about everything that was not mind was a machine, subject to mechanical laws. This was true of the human body and also of the entire cosmos: it was Descartes who established the idea of the mechanical universe, that great piece of engineering which had been set in motion by God but henceforth ran on its own, m accordance with unchangeable natural laws that could be expressed in mathematical formulae.

It was a fruitful suggestion. Scientists like Kepler, Galileo, and finally Newton would supply the proofs for Descartes' world machine. The same mechanistic/dualistic view would affect not only science, but also profoundly influence other aspect of western culture, including religion, philosophy, medicine, psychology and other social sciences. The mechanistic world view had defeated the organic one, and would dominate western society for the next two or three centuries. It is still very much with us, even though it is under attack.

Although we will hear more about it, I do want to make some remarks on the influence of the mechanistic paradigm on education. In view of the many attacks upon this paradigm in recent years, it should be said first of all that it is certainly not to be rejected in toto. The analytical and quantitative methods have been and continue to be fruitful in many areas. So is the faith in objectivity, and, to mention no more, the belief that man is indeed different from the rest of creation.

There are many shortcomings in the mechanistic worldview as well, as holistic educators have not failed to point out. Among them is the almost total exclusion of non-quantifiable disciplines (the humanities, the arts, and so on) as valid ways of knowledge, as well the absolute disregard of subjective, intuitive, or "inner" knowledge – the kind of knowledge as the ancient Hebrews knew it and as the Bible defines it. And as Pascal did, when he said that "the heart has its reasons which reason does not know." Also, the scientific atomistic/analytical approach, while fruitful in many areas, can be quite the opposite in others. Meaning is often sacrificed, as are relationships. Fragmentation rules; it is essential to the method. Yet the whole cannot always be understood from the properties of the component parts: it is much more than its parts. Too often adherents of this paradigm have, at least figuratively, "murdered to dissect." Furthermore, the use of mechanistic models has led not only to serious ecological problems; it has also had disastrous effects on the view man – for example by mechanistic psychology and psychoanalysis: remember Pavlov and the behaviourists, and the determinism of Freud.

Finally, as already implied in much of the above, the application of this paradigm has led to a reductionism that has, again, justly been attacked by the holists. For one thing, it is generally assumed under the modern paradigm that which cannot be observed by the senses or conceived of by the mind is per definition unworthy of consideration. It is also generally believed that some aspects of reality are more real than others, and can be reduced to them. The human, for example, is considered "nothing but" an animal or machine, biology is said to be "nothing but" chemistry, behaviour "nothing but" reflexes, and, as I have said on an earlier occasion, in the view of some cynical teachers young love in springtime is the result of "nothing but" hormonal secretions.

Why it Triumphed←⤒🔗

To return to the historical survey, the question still has to be asked why the mechanistic paradigm triumphed. The answer is: because it worked, witness the tremendous scientific and technological achievements that the western world has seen ever since the scientific revolution. This implied, incidentally, a new criterion for determining and evaluating truth.

Western man still sought truth, but ever since the beginning of the modern period it was a different kind from that sought by, for example, the Greeks or the men of the Middle Ages. The concern for metaphysical or religious truth and certainties faded. To be worth pursuing, truth had to be of a practical, pragmatic nature. That, too, has become part of our paradigm: truth is that which works, that which helps man in his efforts to control nature, and therefore that which enhances his security, his safety, and his well-being.

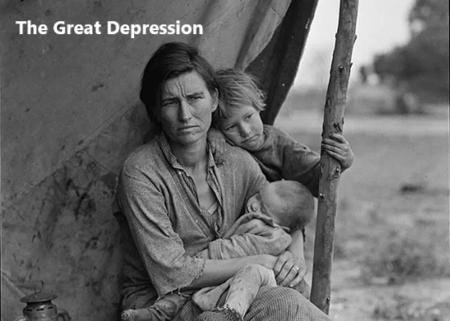

Scientific truth, then, became the only truth worth pursuing, and science became the new religion. For a number of centuries it worked quite well, although there were some early setbacks. The French Revolution, whose instigators had faithfully followed the precepts of Descartes and other Enlightenment thinkers, failed to bring about the promised heaven on earth, creating instead something more akin to hell. The Industrial Revolution, which started around the same time, did much to increase production and prosperity, but had some very depressing side-effects as well: greed and all the vulgarities of excessive materialism and rabid capitalism, as well as grinding poverty for the industrial proletariat, urban slums, filth, and pollution.

The Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was, in many ways, a rebellion against the prevailing world view. Romantics bewailed the filth and suffering of the Industrial Revolution. They rebelled against the cult of reason by stressing the irrational; against the mechanistic world view by returning to nature, which they portrayed as alive and full of feeling; and against the adoration of science by showing its demonic character. It was they, as we saw, who resurrected the Faust legend. Their rebellion, however, was short-lived. They made little more than a dent in the prevailing world view. The world was not yet ready for the combination of holism and irrationalism that the Romantics had to offer. The belief in progress through reason and science was still too strong. It would remain virtually unchallenged during the rest of the 19th century.

The Turning Point←⤒🔗

The turning point came at the end of the 19th century. Then there was a sudden loss of nerve, and a concerted attack on the faith in science, reason, and unlimited progress that had been so strong in the previous period. I have talked and written about this strange fin de siècle phenomenon before and do not want to repeat myself, except to say that the feelings of depression seemed premature. When Nietzsche and other prophets of doom and of the irrational arose, things were not really all that bad in Europe. Some difficulties and potential difficulties there may have been, but there was nothing comparable to the problems faced by the people living at the time of the previous paradigm shift: those of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

That nevertheless the doomsday pronouncements of the fin de siècle were prophetic, and indeed constituted a challenge to the prevailing paradigm, became evident early in the next century. Already in the 1890s there had been predictions of the end if not of the world then at least of the European age. They multiplied after the turn of the century.

As in the period of the Renaissance, there was now also the beginning of a major scientific paradigm shift. But whereas the Copernican-Newtonian revolution had been hailed as a sign of great progress and as indubitable proof of the all-sufficiency of human reason – after all, man had succeeded in penetrating the mysteries of the universe – the work of Einstein, Planck, and their colleagues had the opposite effect. It suggested that the universe was irrational and that man would never know it. The mystery had returned. Around the same time psychoanalysts like Freud and his disciples proved the irrationality of man as well. Artists and authors reinforced the concept. So did the political and social upheavals of the early 20th century: the horrors of World War I, the Russian revolution, the Great Depression, the rise of totalitarian regimes in the 1930s, and so on.

The Existentialist Response←⤒🔗

As had been the case in the Renaissance, people responded to the disasters and dislocations in a variety of ways. I will not try to list them all but deal only with the existentialist philosophy and the New Age movement.

Existentialism was influential especially during the inter-war years, the period of World War II, and the years immediately following. It had arisen earlier. Nietzsche is usually called the father – at least of the atheist branch of the movement. There was also a Christian branch, fathered by the 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. I will concentrate on the atheistic one which had the stronger influence on the western world view.

Existentialism was a pessimistic movement – more pessimistic, I think, than anything we witness in the Renaissance. Existentialists realized that Western man's Faustianism had brought him not a golden age, but one of iron. He had come close to gaining the world, but he had forfeited his soul. His search for truth and certainty had failed. His quest for autonomy and freedom, on the other hand, had succeeded only too well: as Nietzsche was one of the first to declare openly, western man had freed himself even from God – by declaring Him dead. This was not a cause of celebration for either Nietzsche or his followers. Because God was dead, Nietzsche said, meaning had departed from the universe and from human life. Life without God had become absurd, and man faced the abyss, the void, nothingness. As Jean-Paul Sartre, the leader of the French existentialist movement put it, man was condemned to be free, and this freedom was a source of agony and dread.

The picture that perhaps best portrayed the hopelessness and meaningless of existence was that of the ancient titan Sisyphus, as retold by the existentialist philosopher Albert Camus. The gods had condemned Sisyphus to roll a rock up to the top of a mountain, only to see it slip out of his hands at the end of the day and roll back. The futile and hopeless labour had to begin again the next morning, and ad infinitum. That, the existentialists said, is the predicament of western man.

Nihilistic though it was, there is, I think, a certain nobility, even a titanic heroism, to existentialism. Various other people at the time, as also today, attempted to escape from the freedom they did not want and could not handle. They tried to find safety, a sense of belonging, and an antidote to the ever-present sense of dread that the new freedom brought, by joining gangs or totalitarian systems. The existentialists, however, steadfastly refused to follow any such means of escape, and insisted that man must give meaning to life by living it with as much dignity as he could muster. Existence preceded essence. Man makes himself by the way he lives.

The New Age Movement and Holism←⤒🔗

Existentialism has had its day. Its influence is still with us – specifically its subjectivism, its recognition of the loss of absolutes, and its admission that in the end all is vanity. It has strongly influenced art and literature, religion and ethics, and indeed all of western culture, not excluding education. It was too difficult a philosophy for most people, however, and never had many adherents. When, after the second world war, stability and prosperity returned, it faded.

The sense of futility and meaningless did not go away, and the problems in western society continued to multiply also after World War II. In the 1960s we see the rise of other protests groups, which ultimately lead to the New Age movement. And the New Age is far more accommodating to the weaknesses of human nature and the ambitions of mankind than existentialism was, and therefore much more popular.

The New Age movement has been so much in the news that I don't think it is necessary for me to describe it for you in any detail, but let us briefly review its main teachings.

-

Firstly, it proclaims the imminent arrival of a new astrological age, which will be one of peace and universal harmony;

-

secondly, it preaches monism (all is one), pantheism (all is God), and gnosticism (salvation by means of secret knowledge);

-

thirdly, it advocates occult practices such as spiritism, astrology, shamanism, magic, and various methods for inducing altered states of consciousness (including meditation, the chanting of mantras, hypnosis, and mind-altering drugs);

-

and fourthly, it promises that by these means man will be able to tap into the universal energy, partake of the cosmic consciousness, and thereby become god.

You see that some, but only some, of the methods have changed from those employed in the Renaissance. The goal remains the same. It is the old Faustianism under a new name. History has come full-circle.

It is the New Age movement that issues the most direct challenge yet to the Cartesian paradigm, I am not, of course, trying to equate holism with the New Age movement. While all New Agers are holists, the reverse is certainly not true. Yet there are connections between the two, and one may certainly say that the New Age is on the fringe of the holistic movement. I could also turn this around and say that the new holistic paradigm, the one that we will be confronted with more and more, also as teachers, is as much tainted by occultism and paganism as the old one was.

Testing the Spirits←⤒🔗

So what are we supposed to do with all this? What is the moral of the story? We have to realize that we are in the world and can't avoid living with and under the prevailing paradigm or paradigms. But we must, as I said at the beginning, continually test them. This means that we must be aware of them, know them, so that we can consciously select what is acceptable and consciously discard what is not. And we have to be certain about the criteria we use.

There is much that is both appealing and acceptable in the new paradigm, also for teachers. As I tried to show earlier, in the discussion of the effects of the mechanistic paradigm on education, in many ways it can be considered a corrective of the one-sidedness of that paradigm. The reverse is also true. We can learn from both.

Yet there is More to be said. Let me be Brief and Register only a Few Major Points.←↰⤒🔗

Firstly, holism, particularly its more radical fringe, is more outspokenly anti-Christian and pagan than the mechanistic paradigm. The love of ancient paganism is undisguised. It is not at all uncommon to hear reasonably moderate holistic prophets blame the Jewish religion, for example, for the troubles the mechanistic paradigm brought us because the Jews were forbidden to worship Baal and other nature deities. Note also the popularity of such ideas as the Gaia hypothesis, the exaltation of the feminine principle as superior to the masculine, also in religion, the stress on the body and on eroticism as a means of healing, and so on. These ideas will influence educational theories and practices. They already do so.

Secondly, this type of holism has an immediate appeal because it promises community, meaning, togetherness, "spirituality", and similar experiences – all of them much-desired commodities in our love-starved and overly materialistic world – by what are essentially mechanical means. That is, by magic, the chanting of mantras, imaginings, meditations, bodily contact, the adoption of primitive pagan traditions, and so on. This, too, is promoted in the schools. And experience shows that not even Christians are immune. In the Christian press we read of Christian (also Reformed) communities that have begun to practise the chanting of mantras (in this case of the name of Jesus), promote imagining, speak admiringly of the spirituality of native Indians, and so on. The scary thing is that teachers and others can be drawn into this type of practices by following what are, in themselves, acceptable holistic approaches. In this area boundaries are easily crossed.

We therefore will have to test the spirits continually. Remember the warnings in the Bible against exactly this kind of occultism and paganism that we are dealing with – it is the type of self-willed religion forbidden in the second commandment. Realize also its potentially disastrous social consequences. The same author who blamed the Old Testament religion with its prohibition of Baal worship for what he called the disenchantment of the world, warned that attempts at reenchanting the world (I again use his terminology) have led, and can lead again, to whole-scale paganistic orgies as the world witnessed in nazi Germany.

The following quotations express much of what I have been trying to say better than I can do it, and I will conclude with them. They apply to both paradigms. The first one is from C.S. Lewis and was quoted in Christianity Today by Philip Yancey. It says:

For the wise man of old, the cardinal problem of human life was how to conform the soul to objective reality, and the solution was wisdom, self-discipline, and virtue. For the modern mind, the cardinal problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of man, and the solution is a technique.

The other one was found in the same periodical and is from Steve Turner, an English poet and journalist. Turner wrote a critique of current definitions of spirituality, which, he said "are long on deep breathing and Mongolian chanting, but short on authentic biblical faith."

Here follows the quote:

Christian spirituality… cannot be coaxed, kick-storied, or chanted into being. The original temptation is that we can become divine through a mechanical act.

As the end of this last quote reminds us, Faustianism is as old as paradise. None of us is immune from it. And the only way to discern and overcome it is by faith in and obedience to that same Word of God which our modern civilization, under both paradigms, consciously rejects.

Add new comment