John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe

The English Church and the English ⤒🔗

“…in the end the truth will conquer”1

Introduction←⤒🔗

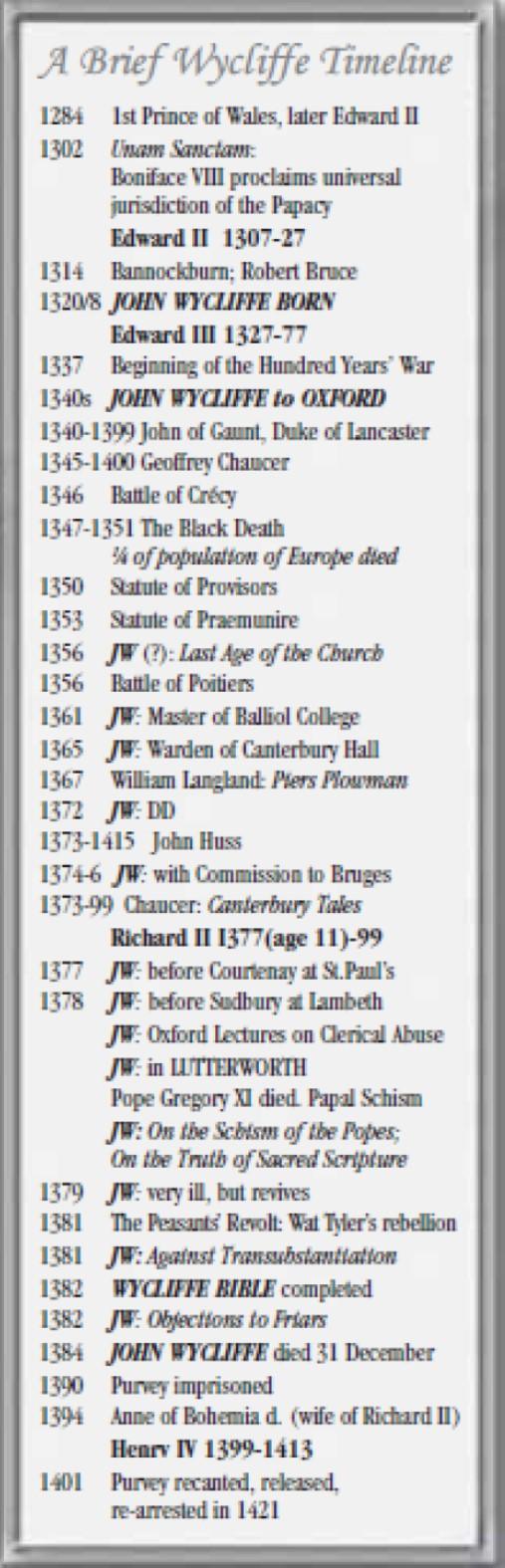

In 1324 Marco Polo, European visitor to Beijing and guest of Kublai Khan, died at home in Venice. The same year is one of the conventional estimates for the birth of John Wycliffe, though as much as four years either way can also be found. There is also a score of spellings of his name, and of suggestions for the location of his birthplace not a few! Wycliffe was wholly a child of the 14th century, probably born in Yorkshire, possibly on Teesside, and in all likelihood went to Oxford aged about 16. There is an obscurity about these beginnings, as with William Tyndale 170 years later, which brings Melchisedek to mind.

It is difficult to enter into the mind, manners, mores and motivation of 14th century Western civilization, but the effort is well worth it. Here, in the sovereign providence of God, is the taproot of Protestantism formed, even though the shoot might not begin to show for another 200 years. The wondrous loop from England to Bohemia to Germany and again to England can be traced over those 200 years, from Lollardy2 at Oxford to Lutheranism at Cambridge.

At the heart of this travel and travail lies the Bible in the common tongue: English, Czech, German, and English again. Between the Lollard Bible of the late 14th century and Tyndale’s work of the early 16th, the change from hand-written copies to printed copies has occurred, and the renewal of competence in the Biblical languages of inscripturation, Hebrew and Greek, has loosed the text of the Bible from the grave-clothes of the Latin Vulgate.3 It is a delicious historical cameo that both Anne of Bohemia (wife of Richard II, d.1394) and Anne Boleyn (wife of Henry VIII, d.1536, same year as Tyndale!) are known to have possessed personal copies of the Wycliffe New Testament.

Papal Europe←⤒🔗

Fourteenth century England can only be seen in the setting of Papal Europe. The dominant and, to contemporaries, the only cohesive power in Europe was the Papacy. This was the bulwark against the encroaching Moors, raiser of Crusades;4 this was the defence against the strange soul-threatening heresies of the Eastern church; this was a peculiar kind of ‘United Nations’ forum, where warring European powers could meet and negotiate, under the wily and acquisitive watchfulness of Vatican politics. Anything but disinterested! If salvation was only to be had in open and unquestioning adherence to the institutional Roman church, then the power of that institution over the politics, finances and morals of ‘Christian’ Europe was absolute.

The dissolute, cruel and ignorant nature of the medieval papacy and priesthood, their greed for wealth, especially the wealth of real estate, whether an entire nation or a tiny manor, are things of record. Pope Gregory IX established the Papal inquisition in 1232, and in 1302 Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the universal jurisdiction of the Papacy. In medieval Europe the significance and value of the individual was zero; you were a fodder producer, cannon fodder or canon-law fodder, bound to the church as much as to the land.

It was indeed ‘a world lit only by fire’,5 scarcely changed technologically since the fall of Imperial Rome. Regression rather than progression was the situation, and more so in the north than in the south. No printing; no light beyond that of a flame; no power beyond that of muscle, wind or water. The mechanical clock was first constructed in 1280, spectacles assembled in 1290, but very few would know of these things, let alone see, use or own them. Learning, such as there was, was the prerogative of the church. True, Paris University was begun in 1155, Oxford in 1167, and Cambridge, by a body of Oxford dissidents, in 1329, but most scholars were, or became, churchmen of some level or other. Such total absorption of all of life within what can only be called an ideological monster is almost beyond our comprehension.

Plantagenet England←⤒🔗

England had come to terms with the Conquest of 1066. Distinctions between Norman and Saxon, victors and vanquished, were being eroded, so that the ‘language curtain’ was coming down. The distinctive use of French as the polite language continued for a very long time, but the writings of William Langland and Geoffrey Chaucer established English, or that Saxon dialect called ‘Middle English’, as a respectable, workable and robust medium of communication.

The Norman royal line had become the House of Anjou, supposedly nicknamed Plantagenets because of the sprig of broom (planta genista) affected as ornament by their great men. Struggles for territory in France rumbled on. Castles in Wales, a Spider in Scotland, Crusades in Outremer, Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest, these were the exciting bits of history in schoolboy recollection, not always strictly accurate6 in fact or chronology!

The insistent dirge permeating all of this was the need to resist the territorial and financial graspings of the Bishop of Rome. In this, England suffered much, but the grotesque humiliation of the nation in King John’s time was to become a mine under the edifice of the papacy. In 1213 King John resigned the power, claims and dominion of the English Crown to the Pope. In 1215 the English barons gathered at Runnymede and obliged John to sign the Magna Carta. This was a first small step towards redefining royal power, which in simplest terms said, ‘The nation, land and people, isn’t yours to give, nor the pope’s to take’. However, the annual payment of 1,000 marks to the papal coffers as a result of John’s pusillanimity continued. Resisting the political and territorial claims of the papacy led through the next three centuries to resisting the ecclesiastical and spiritual claims — led in effect to the English Reformation. Not without cost; and not without reason was it said that the chief enemy of all countries in medieval Europe was always the current Pope.

John Wycliffe lived almost entirely under the reigns of Edward III and Richard H. The unrelenting burden of these monarchs was to fend off papal attempts to maintain and reassert dominion in England. Money was being siphoned away in large amounts through strange ‘cover’ taxes imposed by and collected by the Roman church, a scam further helped by the appointment of nonresident foreign clergy to church posts in England under the labyrinthine rules of papal provisors. These were the issues addressed in England by the Statutes of Provisors (clergy posts) 1350 and Praemunire (money matters) 1353. The trouble was, at any time the papacy could excommunicate you: nonpayment of taxes is a religious matter, endangering the soul! At any time the whole nation could be put under an Interdict, an enforced ‘withdrawal of co-operation’ on the part of the clergy: no proper marriages, baptisms, burials or confessions. How can we possibly enter into the paralysing fear, erosion of courage and suppression of dissent that such things induced in the superstitious minds and hearts of so many in that time? That was a time of monolithic European ecclesiastical power which pretended to have dominion over you, your family, your master, your monarch, your nation, for life, for death and for hell. What was needed was someone to say not just that the church is wrong about this and that particular, but simply, starkly, ‘This church is wrong!’ Wrong because it is comprehensively, demonstrably un-Biblical is in fact no church. There was need for God, who commanded the light to shine out of darkness, to give again by the mirror of His Word the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.7

John Wycliffe, Scholar←⤒🔗

In the 1340s Wycliffe was at Oxford University, just towards the close of the career of Thomas Bradwardine (1290-1349). Bradwardine, then Chancellor of St. Paul’s, London, ‘confessor’ (personal chaplain) to Edward III, and briefly Archbishop of Canterbury in 1349, had been an outstanding alumnus of Oxford. More renowned as a mathematician than as a theologian, Bradwardine nonetheless wrote against the Pelagian teachings in the style of Athanasius and Augustine, insisting that God’s Grace is the ultimate necessity and cause in Salvation. This certainly found a ready place in the thinking of the young Wycliffe, and appeared in his own later tracts and theses as ‘The Dominion of Grace’.8Bradwardine’s solemn insistence that dependence upon outward forms should not be confused with true religion of the heart also grew from seed to fruit in Wycliffe.

The writings of Occam occupied Wycliffe much; his interest in natural science and mathematics was considerable. He won outstanding recognition in philosophy, but applied himself most diligently to the study of theology and of ecclesiastical law. In his approach to this John Wycliffe was a real ‘non-conformist’. At that time — as in some more recent times — it was not really considered necessary to master the Scriptures as a preparation for a church career! Indeed, it was deemed such an elementary book to the proud Latinists of the day that it was almost beneath their dignity to handle it in exposition or teaching. Wycliffe though, became enamoured of the Scriptures, and in his growing practice of reading the Bible in public, and growing confidence in referring to the Scriptures as a sole authority, he earned the name ‘Gospel Doctor’.

By 1361 John Wycliffe was Master of Balliol College, and when that post had to be relinquished because of parish obligations elsewhere, he was appointed as Warden of Canterbury Hall in 1365. Around this same time his writings really begin to have the feel of ‘Reformation’ about them opposing indulgences,9 both in principle and especially in the peddling of them, and opposing masses for the dead, again available more easily to the rich than to the poor. Alongside this, the determination that the truth of the Scripture should be widely and soundly preached as well as read becomes apparent in Wycliffe’s practice. A little later Wycliffe distributed tracts denouncing the secularization of the church. All of this, inevitably, provoked the Pope.

John Wycliffe Clerk, Commissioner and Rector of Lutterworth←⤒🔗

Towards the middle of the 14th century, at the prime of Edward III’s reign, England was in a relatively strong, secure and confident position. The naval victory at Sluys in 1340 had secured the Channel as English, and victories at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) had made her a power to be reckoned with on the Continent. From the fifth year of Edward III the annual papal levy incurred by King John had not been paid.

Then, 33 years on, Pope Urban V demanded, with menaces, the resumption of this transaction. Edward, and Edward’s England, were insulted. Parliament assembled in May 1366, and resolutely denounced and rejected the demand. In the ensuing paperwork, John Wycliffe appears as ‘the King’s Peculiar Clerk’, refuting the claims of the papacy to temporal jurisdiction, and summarising the parliamentary debates accepting Edward of England and rejecting Urban of Rome.

Soon after this, in 1372, Wycliffe became DD. In those days this was a true academic attainment and quite rare, which strengthened his influence and reputation. Both the learned and the common people heard him gladly as he settled more and more confidently on the Bible and its authority, denouncing the ecclesiastical world for effectively banishing the Scriptures and for making the church of Christ a world power.

The problem of the papal use of nonresident foreigners to pre-empt English clergy livings, benefices and appointments, was addressed by a Royal Commission in 1374. A hearing with the Roman authorities was to be held in Bruges, and second on the list of the English Commissioners was John Wycliffe. As a man of outstanding learning and obvious disenchantment towards the papacy, his political stock was high. Perhaps not many had yet seen the ecclesiastical and spiritual aspects and implications of Wycliffe’s course. From August 1374 to July 1376 Commissioner John Wycliffe was in Bruges, where he concluded that the faults and failings of the papacy, temporal and spiritual, were more abysmal than he had ever learned in England. He also made there a firm friendship with John of Gaunt (Duke of Lancaster, 3rd son of the King), and on his return to England was looked on with sufficient favour as to be given the living of Lutterworth, in Leicestershire.

Opposition Grows←⤒🔗

Hostility towards Wycliffe was inevitable, eagerly fomented by the ranking churchmen in England and encouraged in every way by the papal authorities in Europe. In February 1377 he was cited by the Bishop of London to appear at St. Paul’s to answer charges against his teachings. Wycliffe duly appeared before Bishop Courtenay, accompanied in close friendship and support by John of Gaunt and Lord Percy, the Earl Marshall of England. These two were not inclined to allow Wycliffe to be bullied by a court which had the ground of its authority not in England, but in Rome. Only Wycliffe remained calm in the uproar and violence that developed and lasted over into the next day. Although he was dismissed with warnings, no formal procedures were accomplished, and Wycliffe went about his business. His enemies made a selection of points from his lectures and letters plainly stating his opposition both to the Pope’s temporal powers and to the abuse of Spiritual power. In May 1377 five separate Bulls10 were dispatched to England, demanding that Bishops, University and King should apprehend John Wycliffe and detain him at the Pope’s pleasure.

For a little while nothing happened, because King Edward III died in June. His first son, Edward, the ‘Black Prince’, had died in 1376. The crown passed to the eleven-year-old Richard II, son of the Black Prince, grandson of Edward III. Richard’s mother was sympathetic to Wycliffe, along with John of Gaunt,11 affording a continuance of protection. When eventually Archbishop Sudbury summoned Wycliffe again to appear, this time at Lambeth in April 1378, the dowager Queen forbad the bishops to pass censure on him. Again the defendant alone remained calm, and 150 years in anticipation of Luther’s justly famed confession (‘Here I stand — I can do no other’), John Wycliffe declared that he only followed the Scriptures, and if shown to be wrong by the Scriptures he would retract his teachings.

All of this directed attention towards Wycliffe’s teaching in its wider implications Scripture alone the fountain of truth and foundation of authority, and anything not framed by such a measure was not to be imposed nor obeyed, whether in things temporal or in things spiritual.12 Wycliffe’s career in the political limelight was over. John of Gaunt’s influence was temporarily diminished, and he (Gaunt) was also becoming a little wary of the more religious aspects of Wycliffe’s teaching. Preaching, teaching, and translation work would occupy Wycliffe, living at Lutterworth, for the last seven years of his life.

‘Ex Cathedra’, or, how many Popes can sit on one Chair?←⤒🔗

In 1378 an event came to pass which stunned and horrified the Western World. When Gregory XI died, Clement VII was elected Pope. Rome’s inhabitants demanded an Italian as the Bishop of Rome, and thus Pope, and the unthinkable was accomplished. French Clement was obliged to set up his ‘court’ as Pope in Avignon, whilst Italian Urban VI ruled as Pope in Rome. The infamous ‘Papal Schism’ had occurred. This beginning of the Great Schism came when Wycliffe was coming to maturity in his realisation of the wrongs of the Papacy, and when he had more time away from the political arena.

In 1378 Wycliffe issued a tract On the schism of the Popes; in 1381 he issued Twelve theses against transubstantiation and in 1382 Objections to Friars. In addressing these issues — the papacy, the mass and the monks — in their corruptions and in their lack of Biblical warrant or foundation, Wycliffe laid the axe to roots of the tree. It was an axe which many subsequently would wield mightily, even at the hazard of their lives, and turn the world upside down once again, in the footsteps of the Apostles. To John Wycliffe, scholar, these doctrines, parading in the garb of Christian Truth, were relative novelties. Transubstantiation as the grossly externalised means of Communion with Christ, was proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1215, as was the procedure of confession of sins to a priest. The universal supremacy of the papacy was promulgated by Pope Boniface VIII in 1302.12 As for the monks — the vileness and violence of so much involved with them was such that some respectable families declined to have their children educated formally, because it would expose them to the predatory appetites of their monk-teachers.

Having crossed this Rubicon, Wycliffe never let up in his march on Rome, and most of all opposed that grotesque view, according to which any priest was in a position to ‘create’ the body of Christ. He resolutely denounced, as contrary to Scripture, the teaching that after the consecration the bread and the wine are changed into Christ’s body and blood.

Wycliffe’s perception of the church was implicitly revolutionary and anticipatory of the sixteenth century Reformation. Driven by the calamitous failure of the medieval church in the political arena, he began to see the church as a spiritual institution and not a political one. He left as a magnificent heritage the principle that the visible church, in all its parts, powers and persons, is ever subject to evaluation in the light of Scripture only. Even if there should be a hundred popes, let alone two, they must come to the court of Scripture to be adjudged as to their right and worth.

The Truth of Scripture and The Lollard Bible←⤒🔗

The mainspring of Wycliffe’s mature work was that the Scriptures are the foundation of all doctrine. This was the crux of the matter, the cardinal hinge. His 1378 work De veritate Sacral Scripturae (On the Truth of Sacred Scripture) describes the Bible as being directly from God Himself, timeless, unchanging, free from error and contradictions, containing only truth, accepting no addition, suffering no subtraction. All must be taken equally, absolutely, without qualification. Scripture is the law of Christ, the Truth, and must be placed above all human writings. Men ought to learn the law of Christ, because the faith rests in it alone. Without knowledge of the Bible there can be no peace, no real and abiding good; it contains all that is necessary for the salvation of men. It alone is infallible, and therefore is the one authority for the faith. As a true Christian will be one who finds his faith in the light of Scripture, so a true Shepherd of Christians will be one who feeds his flock on the Word of God. A hundred years before Luther or Tyndale was born, Wycliffe was comprehensively persuaded of the importance of Scripture.

For Wycliffe, as later for Luther and Tyndale, the next step was inevitable. The Bible must be available for the people in their mother tongue. Roman apologists are quick to point out that there were portions of Scripture in many of the European languages; but they were not generally accessible. Whilst the Council of Nicea in 325 had been of the opinion that no Christian should be without the Scriptures, the Council of Toulouse in 1229 was of a different mind. Trying to deal with the ‘problem’ of the Albigenses, canon13 of their deliberations reads:

We prohibit also that the laity should be permitted to have the books of the Old or New Testament; unless anyone from motive of devotion should wish to have the Psalter or the Breviary for divine offices or the hours of the blessed Virgin; but we most strictly forbid their having any translation of these books.14

Such Scripture portions as did exist in the vernacular tongues were rather a ‘private’ resource for the ‘religious’ or ‘spiritual’ than the ‘Word of God among all nations’. Wycliffe did not simply want circulation to the learned or spiritually experienced; he was of the same mind as Tyndale 150 years later, that the Scriptures should widely be published abroad, accessible, that men might know not only the Truth of the Gospel, but also the errors of the supposed guides to God. He set himself to the task

Whilst scholars still struggle to define the exact part which he had in the translation, there is no doubt that it was the result of his initiative and leadership.15 The first Wycliffe Bible, c.1382, comprises a translation of the New Testament deemed to be by Wycliffe himself, together with one of the Old Testament done by a friend, Nicholas of Hereford, who was to be the Lollard leader after Wycliffe’s death (but who later recanted and ended his days as a Carthusian monk). This Old Testament is sometimes held up to ridicule because of an unfortunate adherence to the word order of the Latin Bible from which it was translated. It makes clumsy and sometimes contradictory reading in English. Wycliffe’s New Testament is more boldly and readably English, though still translated from Latin.

This work was revised in 1388 by a younger contemporary, John Purvey, after Wycliffe’s own style. It is this smoother, truer version which is the Lollard Bible, widely diffused through the 15th century. Every copy was hand-written, and although the number of copies made was relatively large and continued over the next 150 years, it was never a ‘mass-produced’ book Once again we are constrained to marvel at the unfolding, working together of the purposes of Almighty God, in that English as a language of literacy was coming into its own in the 14th century, just as the Lollard Bible began to circulate.

Books had always been a luxury in the Middle Ages, but the production of cheaper books on the new material, paper, meant that they became an ‘affordable’ luxury for poorer people, people with a hunger for ‘the holy scriptures, which are able to make ... wise unto salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus’ (2 Timothy 3:15). Bear in mind, though, that the opposition was fierce and merciless. Possession of such a Bible, let alone reading it or revealing a sympathy with its teaching, was potentially a matter of death, and many died. Nevertheless, in England now the sure Word was heard in a familiar tongue, and men began to give heed as to a light that shineth in a dark place.

Lollard-Preachers←⤒🔗

It was not to be expected that someone of john Wycliffe’s conviction would neglect the due companion to the distribution of Scripture, which is the public reading and preaching of the same. In Lutterworth he gave himself to the care of souls, toiling as preacher and teacher to the people. He wished to be done with the existing church hierarchy, for it had no warrant in Scripture, and to put in its place the sending of ‘poor priests’ who lived in poverty and preached the Gospel to the people.

These itinerant preachers published abroad among the people the teachings of Wycliffe, even ‘Christe’s Lore’. Like Jesus’ disciples before them they went two by two. They went barefoot, wearing long red robes, and carrying a staff in symbolic reference to their shepherd calling. They passed from place to place opening the Scriptures, preaching Christ’s Law, and the Scripture as the all sufficient source of it: and they suffered and they were killed. Well might we be tempted to say ‘of whom the world was not worthy’.

Even up to 1520 followers of Wycliffe were being martyred as Lollards’. Soon after that the charge changed to ‘Lutheran’ or ‘Protestant’. These dear souls carried the torch of the English Bible from the 14th to the 16th century, and when the printing presses were about to serve the Protestant Reformation, handed that torch on to Tyndale, Coverdale, the Geneva scholars, and so to the Translators of the Authorised Version. All of these later workers were aware of the Wycliffe Bible; they were reaping where he had sown.

The failure of Hereford and Purvey to provide leadership into the 15th century meant that Lollardy was always a ‘grass roots’ movement. It was diffuse, diverse, never an organisation or institution, reflecting, unconsciously perhaps, Wycliffe’s perception of the spiritual rather than political nature of the Church of Jesus Christ. Thus there was a savour of salt through England, a taste for a readable Bible to be a guide to Christ and rule of conscience, and some who had ears to hear. Alongside that there was a suspicion of all that smacked of priestcraft. Wycliffe, his Bible, his ‘poor priests’ and the Lollards, spread tinder through the land. (The trail also crossed to the Continent through Huss.) It was well dried by the heat of persecution. Then, after a brief ‘night watch’ of 100 years, the Lord was pleased to kindle that which He had so long prepared, and the Reformation was begun.

Death and Disinterment←⤒🔗

During the last week of December 1384 Wycliffe was stricken with a paralysis whilst conducting the service of the Lord’s Supper in Lutterworth Church. Carried by his friends to his own bed he died peacefully there on December 31st. Baulked of their desire to destroy Wycliffe in person, the church powers ensured that the opposition to the English Bible and Wycliffe’s teachings did not diminish. An Oxford Convocation of 1408, headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, declared thus,

We therefore decree and ordain, that from henceforward no unauthorised person shall translate any part of the holy Scripture into English or any other language, under the form of book or treatise, neither shall any such book, treatise, or version, made either in Wickliffe’s time or since, be read, whether in whole or part, publicly or privately, under the penalty of the greater excommunication.16

A Papal Council of 1415, the one which deceitfully lured John Huss to a martyr’s death, declared Wycliffe a heretic and demanded that his remains be exhumed and destroyed. In 1428 this was done, and Wycliffe’s bones were burned, the ashes cast into the River Swift which joins the Avon at Rugby, then on into the Severn at Tewkesbury and so to the open sea. Symbolically, unintentionally, the church authorities had enacted exactly what God had done with the ministry of Wycliffe and the English Bible, giving rise to a popular jingle, found in many forms and variations of wording — ‘Avon into Severn flows, and Severn to the sea, and wheresoe’er the ocean rolls, there Wycliffe’s ashes be’.

There can scarcely be a better summary of all this than the inscription on Wycliffe’s Memorial in Lutterworth:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF

JOHN WICLIF

EARLIEST CHAMPION OF ECCLESIASTICAL

REFORMATION IN ENGLAND.

HE WAS BORN IN YORKSHIRE IN THE YEAR 1324.

IN THE YEAR 1375 HE WAS PRESENTED TO

THE RECTORY OF LUTTERWORTH:

WHERE HE DIED ON THE 31ST OF DECEMBER 1384.

AT OXFORD HE ACQUIRED NOT ONLY THE

RENOWN OF A CONSUMMATE SCHOOLMAN,

BUT THE FAR MORE GLORIOUS TITLE OF

THE EVANGELIC DOCTOR.

HIS WHOLE LIFE WAS ONE PERPETUAL

STRUGGLE AGAINST THE CORRUPTIONS

AND ENCROACHMENTS OF THE PAPAL

COURT, AND THE IMPOSTURES OF

ITS DEVOTED AUXILIARIES,

THE MENDICANT FRATERNITIES.

HIS LABOURS IN THE CAUSE OF SCRIPTURAL

TRUTH WERE CROWNED BY ONE IMMORTAL

ACHIEVEMENT, THE TRANSLATION OF THE

BIBLE INTO THE ENGLISH TONGUE.

THIS MIGHTY WORK DREW ON HIM,

INDEED, THE BITTER HATRED OF ALL WHO

WERE MAKING MERCHANDIZE OF THE

POPULAR CREDULITY AND IGNORANCE:

BUT HE FOUND AN ABUNDANT REWARD IN

THE BLESSINGS OF HIS COUNTRYMEN OF

EVERY RANK AND AGE, TO WHOM HE

UNFOLDED THE WORDS OF ETERNAL LIFE.

HIS MORTAL REMAINS WERE INTERRED

NEAR THIS SPOT; BUT THEY WERE NOT

ALLOWED TO REST IN PEACE.

AFTER THE LAPSE OF MANY YEARS, HIS

BONES WERE DRAGGED FROM THE GRAVE,

AND CONSIGNED TO THE FLAMES:

AND HIS ASHES WERE CAST INTO THE

WATERS OF THE ADJOINING STREAM.

Add new comment