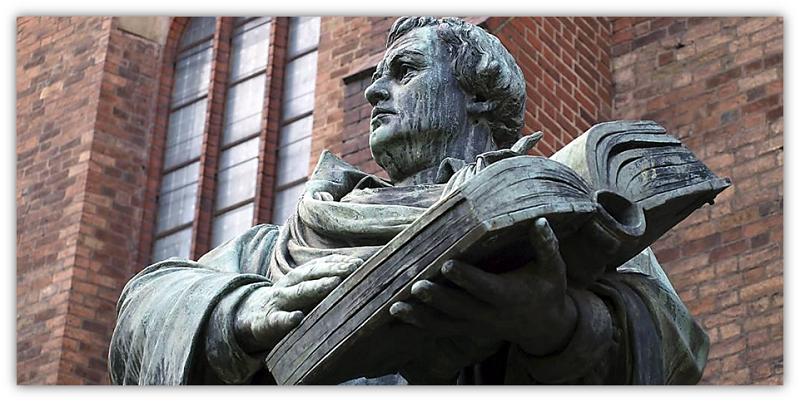

Civilization and the Protestant Reformation

Civilization and the Protestant Reformation

Civilization as we know it began on October 31, 1517. In the small east German town of Wittenberg, a thirty-year-old Augustinian priest walked to Castle Church and nailed ninety-five theological propositions for debate on the door. The debate Martin Luther began nearly 500 years ago turned the world upside down. Democracy, civil rights and liberties, constitutional government, religious liberty, and the free market all find their roots in the Reformation.

The occasion for the debate was the fundraising practices of the pope's representatives in Germany. As a Catholic priest, Luther was concerned that a representative of the pope was telling his parishioners that they could purchase forgiveness for their sins. Luther knew that God alone could forgive sins, and that salvation could not be purchased for any amount of money: It was a free gift of God.

Pope Leo X, engaged in an expensive cathedral building program in Rome, had authorized a Dominican monk and church inquisitor named Johann Tetzel to sell indulgences in Germany. Indulgences were personalized certificates which promised forgiveness of sins and assurance of salvation. Tetzel exaggerated even the preposterous claims the pope had authorized him to make. He preached to whomever would listen: "Indulgences are the most precious and the most noble of God's gifts ... Come and I will give you letters, all properly sealed, by which even the sins that you intend to commit may be pardoned ... But more than this, indulgences avail not only for the living but for the dead ... Priest! Noble! Merchant! Wife! Youth! Maiden! Do you not hear your parents and your other friends who are dead, and who cry from the bottom of the abyss: 'We are suffering horrible torments! A trifling alms would deliver us; you can give it, and you will not!'" Who could resist Tetzel's ingenious appeals to both selfishness and love of parents?

Tetzel had a fee schedule for the forgiveness of sins:

Witchcraft, 2 ducats. Polygamy, 6 ducats. Murder, 8 ducats. Sacrilege, 9 ducats. Perjury, 9 ducats.

Other indulgence sellers in other regions charged different fees, depending on the gullibility of the people. Gold and silver flooded into the pope's treasury in Rome.

When Luther protested the sale of indulgences, he assumed that he would have the support of the pope: He saw himself as merely attacking the abuses of ecclesiastical power, not the church itself. He wrote later that he had been "a monk and a most enthusiastic papist when I began that cause ... I certainly thought that in this case I should have a protector in the pope, on whose trustworthiness I then leaned strongly..." But he soon learned differently, as Pope Leo X supported his fundraisers and excommunicated Luther for his refusal to be silent.

What began as a debate over fundraising quickly turned to a more fundamental and serious issue: How is salvation obtained? Luther's answer — that men are saved by the righteousness of Christ alone ascribed to them through faith in Christ alone — shattered the entire medieval structure of ecclesiastical and political authority. Luther's appeal was to "Scripture and clear reason," not to the statements of church councils, nor to the decrees of popes, nor to the hierarchy of the church. Unless an idea or a practice is taught by Scripture, Luther argued, it has no authority and is anti-Christian.

The old world, the medieval world, was a world controlled by an all-powerful monarchical church and state. It was a thoroughly corrupt system, rotten from the head down. In 1510 Luther had traveled to the center of the old world, the city of Rome, where he witnessed the moral squalor and material opulence of the papacy. Despite the decadence of the church, Luther's central concern was neither its materialism nor its immorality, but the teaching of the church on salvation. It was that teaching that was not only filling the papal treasury, but was sending souls to hell. The central human question is: How can sinful men stand before a holy God and live? That question had become a consuming personal issue for Luther: How can I, Martin Luther, a sinful and miserable man, stand before God and live?

The official answer the Roman Catholic church gave — that God infuses the required righteousness into the hearts of the faithful — troubled Luther. In theory, the church's answer meant personal righteousness. In practice, it meant works. No one in all of Christendom was more fervent in seeking salvation than the monk Luther, yet he could not find the required righteousness within himself. All his prayers, masses, penance, fasting, and good works could not merit the favor of God. Luther was a lost soul, and he knew it.

Then, while studying the Bible, Luther discovered the idea that men are not saved by church rituals or good works, but through faith alone: "The just shall live by faith." He read the apostle Paul's letters to the Romans and the Galatians, where Paul taught that "a man is justified by faith apart from the deeds of the law" Now Luther understood how God provided salvation for His people, and his understanding would change the world forever.

Religious Subjectivism and Stagnation⤒🔗

For a thousand years, because of the church's doctrine of justification as an internal grace rather than the objective, external legal declaration of a sinner's innocence by God, men had looked inside themselves for the graces that merited salvation. The more devout retreated to monasteries and convents to find their salvation in their interior lives. Some sat on poles, some beat their bodies bloody, and some made pilgrimages to "holy" places. The church had lost the message of the gospel, that men are saved by a righteousness wholly outside of themselves — the righteousness of Christ. By His perfect life, innocent and substitutionary death, and bodily resurrection, Christ had fulfilled the demands of God's law on behalf of all who believed in Him. It is to Christ that one must look for salvation, said Luther, not inside oneself. Once the religious subjectivism of the medieval church was eliminated in Protestant countries, the energy consumed by desperately seeking and "earning" salvation was turned outward, and a thousand years of intellectual, political, social, economic, and religious stagnation ended.

The Priesthood of All Believers and Democracy←⤒🔗

Martin Luther also realized that the sacramental system of the church — by which the church claimed to save some people and to damn others — is contrary to Scripture: Each believer is a priest, and he needs no other than Jesus Christ to stand between himself and God. The pope, the bishops, and the priests, rather than leading souls to heaven, blocked their way.

The death and resurrection of Christ had guaranteed free access of all believers to God. Justification came only through belief, not through baptism, nor through the mass, nor any other sacrament, and certainly not through good works. Luther articulated the idea of the priesthood of all believers, and it became the foundation for modern political democracy — the equality of all men before God and the law. Ecclesiastical monarchy and aristocracy were destroyed by the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers, and with them went the theological underpinnings for civil monarchy and aristocracy.

The Bible Alone and Constitutionalism←⤒🔗

Luther's love for truth drove him on. The pope had erred in his teaching about indulgences, and therefore the pope was not infallible. In fact, the pope and church councils had made many errors over the centuries; they were not to be trusted, especially with something so important as the salvation of one's soul. Luther wrote: "I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves." The only thing trustworthy was the Word of God itself, the Bible.

The medieval structure of ecclesiastical authority could not withstand the Protestant idea of sola scriptura — the Bible alone. One Christian man with a Bible was superior to any pope or council or tradition without it. Luther translated the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into German so the people could read it in their own language and not be subject to an ecclesiastical ruling class. By translating the Bible into the common language, Luther freed the German people from ecclesiastical totalitarianism: The Bible was the written constitution of the church, which the people could now read for themselves. His second major contribution to Western political thought was the idea of a written constitution — the Bible — limiting the power and authority of church (and later political) leaders. There is a direct connection between the Reformation cry of sola scriptura and the American idea of the Constitution — not any man or body of men — as the supreme law of the land.

Christian Faith and Religious Liberty←⤒🔗

Luther argued that Christians were free from the arbitrary control of either the church or the state. God alone is lord of the conscience... Religious liberty, freedom of conscience, is an idea that Luther derived from the Bible's teaching about faith: Belief is a gift of God; it is not a work of man's free will. Men cannot believe the gospel unless God causes them to. Luther wrote: "God's Word should be allowed to work alone, without our work or interference. Why? Because it is not in my power to fashion the hearts of men as the potter molds the clay ... I can get no further than their ears; their hearts I cannot reach. And since I cannot pour faith into their hearts, I cannot, nor should I, force anyone to have faith. That is God's work alone, who causes faith to live in the heart ... We should preach the Word, but the results must be left solely to God's good pleasure." By articulating the biblical doctrine of faith as wholly a gift of God, Luther undermined the Catholic inquisition and formulated the theological rationale for religious liberty.

The Reformation in Law and Economics←⤒🔗

Democracy, constitutionalism, and religious liberty were not the only social consequences of the Reformation. They were the beginning of a revolution that has implications for all aspects of life even five centuries later.

Harold Berman of Emory University has pointed out that "the key to the renewal of law in the West from the sixteenth century on was the Protestant concept of the power of the individual, by God's grace, to change nature and to create new social relations through the exercise of his will. The Protestant concept of the individual became central to the development of the modem law of property and contract..." This, along with Luther's idea that all callings — all labor, not just the labor of monks and nuns — could be done to the glory of God, led to the development of the free market economy. A free society and a free market were the political and economic expressions of the religious ideas of the Reformation. Capitalism was the economic practice of which Christianity was the theory.

One of Luther's most brilliant followers, John Calvin, systematized the theology of the Reformation. The seventeenth-century Calvinists laid the foundations for both English and American civil rights and liberties: freedom of speech, press, and religion, the privilege against self-incrimination, the independence of juries, and the right of habeas corpus, the right not to be imprisoned without cause. The nineteenth-century German historian Leopold von Ranke referred to Calvin as the "virtual founder of America."

The German sociologist Max Weber wrote a book in 1908 titled The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in which he argued that capitalism historically emerged in Protestant countries because they inculcated those virtues that led to the development of capitalism: hard work, honesty, frugality, thrift, punctuality. These virtues, coupled with the idea of a calling, provided the impetus ending serfdom and establishing a free political and economic order. The theology and values of the Bible, rediscovered by the Protestant Reformers in the sixteenth century, have been the principal ideas creating what we know as Western civilization.

All These Things←⤒🔗

It was not Luther's intention to create a civilization; he intended to proclaim the righteousness of God in Jesus Christ. His life was dedicated to a far more important activity than building an earthly city. Western civilization was an unintended byproduct of his faithfulness to the Bible. The Reformation put the kingdom of God first, not the kingdom of man or the kingdom of the church. The results were just as Christ said they would be in Matthew 6:25-33.

Justification by faith — the righteousness of God imputed to sinners — is the only foundation of eternal salvation and earthly civilization. The Reformers sought first the kingdom of God, and all these things — the things we call western civilization — were added to them, and to us.

Add new comment