Calvin at Five Hundred ‘OMNI AD DEI GLORIAM’

Calvin at Five Hundred ‘OMNI AD DEI GLORIAM’

Introduction⤒🔗

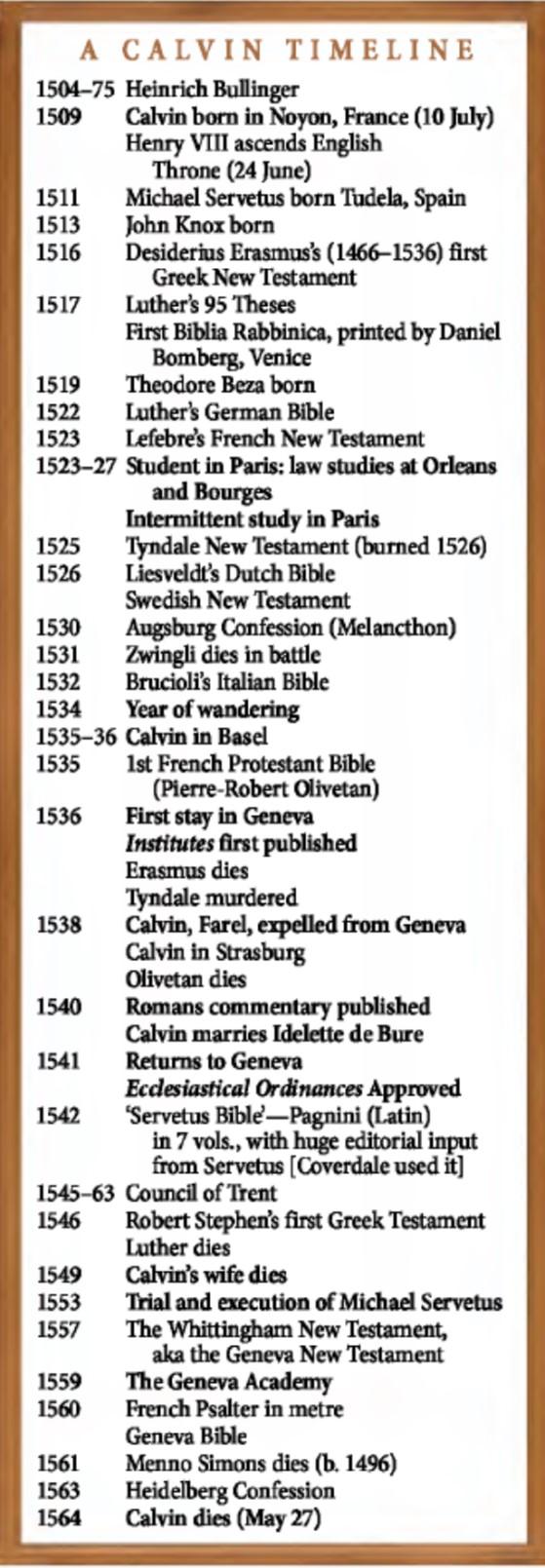

On 10 July 1509, five hundred years ago, John Calvin (Jean Cauvin) was born in the Place au Blé (cornmarket) at Noyon, Picardie, sixty miles north east of Paris. 1 There will be many tributes, faint praises and assaults, in religious publications just now, but the aim of this article is to concentrate on Calvin in connection with the Scriptures. Leaving polemics aside, so far as is possible, by relying heavily on Calvin’s own words, there will be:

- The setting

- A brief sketch of Calvin’s life

- Calvin and Scripture

- Résumé and reflections

- Appendices

The Setting←⤒🔗

When the 16th century began, Western Europe had only one visible ‘Christian religion’, Roman Catholicism: a church rich and powerful, and having a weight of historical inertia to preserve it. But this appearance of ‘a monolith’ was superficial. There were opponents, dissidents: separated, hated, pursued and persecuted to death, but bearing an unquenchable witness to the better promises of Christ’s Gospel. There were also many inherent flaws, so that disputes and lax practices had grown up within the church. Churchmen criticised the administration of the church and began uncomfortably to doubt some teachings, particularly the insistence that it alone had the authority to interpret the Bible. From the 14th century, John Wycliffe had declared that all people had the right to read the Bible and interpret it for themselves.2 He and his disciples sought to enable this, translating the Latin Bible into English in 1382. Wycliffe’s Biblical ideals spread into Bohemia, where Jan Hus preached them widely, in powerful sermons, until his martyrdom. The cumulative work of Wycliffe and Hus greatly influenced a Saxon monk named Martin Luther. With his painfully learned grasp of the authority of Scripture, the true meaning of ‘poenitentia’3 and of justification, the word ‘Reform took on a powerful new thrusting influence under God. But it was not only the ecclesiastical map of Europe that was transformed in the 16th-century Reformation, but the political, and more significantly, the spiritual.

Outline of Calvin’s life←⤒🔗

Calvin’s father was notary to the bishop of Noyon. Because of this his son, as a child, was given a cathedral canonry, the income of which would pay for his education. In the preface to his July 1557 Commentary on the Psalms4Calvin tells us that:

...when I was as yet a very little boy, my father had destined me for the study of theology. But afterwards when he considered that the legal profession commonly raised those who followed it to wealth this prospect induced him suddenly to change his purpose. Thus it came to pass, that I was withdrawn from the study of philosophy, and was put to the study of law.

From the age of fourteen he followed legal studies in Paris, Orleans and Bourges, and records that:

To this pursuit I endeavoured faithfully to apply myself in obedience to the will of my father; but God, by the secret guidance of his providence, at length gave a different direction to my course.5

The situation in France became precarious because of the influence of reforming teachings, to which Calvin also began to respond. On 1 November 1533, Calvin’s friend Nicholas Cop, rector of the University of Paris, gave a public address from Romans 3:28 ‘Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith without the deeds of the law’, openly supporting reform and stirring up fierce hostility. By 1535 Calvin was constrained to flee to Basel, Switzerland. Already the patterns of rigorous studying and fasting were established, yielding result in his spiritual, Biblical and language labours, but also a lifelong susceptibility to severe migraines and distempers of lungs and digestion. It is during these next few years that we can place what little we know of Calvin’s conversion experience, which also implies a call to the later work:

...since I was too obstinately devoted to the superstitions of Popery to be easily extricated from so profound an abyss of mire, God by a sudden conversion subdued and brought my mind to a teachable frame, which was more hardened in such matters than might have been expected from one at my early period of life. Having thus received some taste and knowledge of true godliness I was immediately inflamed with so intense a desire to make progress therein, that although I did not altogether leave off other studies, I yet pursued them with less ardour. I was quite surprised to find that before a year had elapsed, all who had any desire after purer doctrine were continually coming to me to learn, although I myself was as yet but a mere novice and tyro.6

The Pastoral Purpose of the Institutes ←⤒🔗

While he was in Basel the newly-awakened Reformer published a small book about his beliefs. This, the first edition of the Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1536, contained only six brief sections; by 1559, the last edition, it had grown to seventy-nine substantial chapters. As with so many great Christian works, the first motivation was intensely ‘pastoral’, a shepherd’s bold and unselfish care for a flock, as Calvin informs us:

This was the consideration which induced me to publish my Institute of the Christian Religion. My objects were, first, to prove that these reports (of the errors of ‘many faithful and holy persons ... burnt alive in France’) were false and calumnious, and thus to vindicate my brethren, whose death was precious in the sight of the Lord; and next, that as the same cruelties might very soon after be exercised against many unhappy individuals, foreign nations might be touched with at least some compassion towards them and solicitude about them. When it was then published, it was not that copious and laboured work which it now is, but only a small treatise containing a summary of the principal truths of the Christian religion, and it was published with no other design than that men might know what was the faith held by those whom I saw basely and wickedly defamed by those flagitious and perfidious flatterers.7

Calvin, ever seeking seclusion for study, determined to go to Strasbourg. Warring conditions meant that the best route lay through Geneva, where William Farel and Peter Viret were involved in a different kind of war — Reformation, and that of the fiercer kind! In his own words again, Calvin declares:

William Farel detained me at Geneva, not so much by counsel and exhortation, as by a dreadful imprecation, which I felt to be as if God had from heaven laid his mighty hand upon me to arrest me.8

God had joined Calvin and Geneva, and all attempts to put them asunder ended in failure. Even his banishment to Strasbourg, 1538-41, was blessed of God, and he counted those few years as pastor of that city’s French congregation most happy. There he published his seminal, influential commentary on Romans, and married Idelette de Bure, widow of a converted Anabaptist.

Geneva prevailed upon Calvin to return there, which he did, taking up his course of ministry at exactly the point where he had been compelled to leave it, almost in midverse, three years before. His wife died in 1549, but Calvin’s weighty ministry continued. He was preaching (almost daily, extemporarily, from original language texts9), lecturing, writing and revising his commentaries and further editions of the Institutes, maintaining correspondence throughout Europe,10and meeting the demands of the Geneva Academy. He was much consulted in city affairs, very influential but never holding formal office.

Calvin’s death was an anguished but courageous and faithful event, Christdependent and prayerful, as was every other part of his Christian experience. I can never read of his painful trotting on horse round the city, attempting to pass a large kidney stone, without wishing that some of his implacable character assassins would read it too (and of his loss of a prematurelyborn son, August 1542; and the affecting exchanges between himself and Idelette on her deathbed); however, the ‘sympathy play’ would be unworthy of the man, and establishes no truth of itself. The Geneva ministers had removed their weekly meeting to Calvin’s home when he was no longer able to come to them, and gathered with him one last time on 9 May 1564. He died 27 May, and I give you the closing words of his preface to the Commentary on Daniel to serve as his own epitaph 11:

I have dedicated to you this my labour, as a pledge of my desire to help you, until at the completion of my pilgrimage our heavenly Father, of his immeasurable pity, shall gather me together with you, to his eternal inheritance. May the Lord govern you by his Spirit, may he defend my most beloved brethren by his own protection, against all the plots of their enemies, and sustain them by his invisible power. John Calvin, Geneva, 19 August 1561

The Exegetical Purpose of the Institutes, a Bridge to Calvin and Scripture←⤒🔗

Was Calvin a heavy theologian who also did some commentaries? Was Calvin primarily a preacher of the Scriptures who also did some theological writing? It is a false distinction. John Calvin was in all simplicity a Biblical theologian, whether expounding or summarising. In his last revision of the Institutes he makes it plain: Scripture first and last.

...my object in this work has been, so to prepare and train candidates for the sacred office (the ministry), for the study of the sacred volume, that they may both have an easy introduction to it, and be able to prosecute it with unfaltering step; for, if I mistake not, I have given a summary of religion in all its parts, and digested it in an order which will make it easy for any one, who rightly comprehends it, to ascertain both what he ought chiefly to look for in Scripture, and also to what head he ought to refer whatever is contained in it. Having thus, as it were, paved the way, as it will be unnecessary, in any Commentaries on Scripture which I may afterwards publish, to enter into long discussions of doctrinal points, and enlarge on commonplaces. Preface to last edition of the Institutes, 1559

The mature Institutes, then, are handmaiden to the Commentaries on the Bible. For want of this understanding much harm has been done to Calvin and ‘Calvinism by friend and foe alike. For all who consult to learn from the Institutes, how many consult to learn from the Commentaries? I would in all humility suggest that the Institutes are most useful to us, not as a stand-alone systematic theology, but as a Bible handbook, and as such, the key to understanding Calvin and Scripture.

Calvin and Scripture←⤒🔗

The lead soldiers of the printing press were storming the citadels of medieval scholarship: affordable editions of Latin and Greek classics, with Greek and Hebrew Bibles, were becoming ever more widely available. While he studied law at Orleans, certain of Calvin’s friends had been moved towards Christ and Reform. One was his cousin, Pierre Robert, called Olivetanus (‘Midnight Oil’) because of his late night studying. By this influence, Calvin began reading the Bible, and entered on the study of both Greek and Hebrew.12In Basel, where twenty years before Erasmus had published his Greek Testament, Calvin furthered these attainments. To have a true appreciation of and confidence in Calvin the author of the Commentaries and the Institutes; preacher of great authority; counsellor and confidant to crowned heads,13 ministers, translators and publishers throughout Europe; director of the Genevan reformation — one must accept his utter competence in the Scriptures, Greek and Hebrew first, Latin with equal competence, and the vernacular French. (As with many early Protestant preachers involved also with Bible translation and revision, he is accounted a pioneer in the modern development of his mother tongue.)

Calvin on Scripture:←↰⤒🔗

In the Institutes, Book I, Chapter 7, Section 1, (hereafter in the form Inst. I:7,1, etc.) we read that:

the testimony of the Spirit is necessary to give full authority to Scripture.

Section 4 concludes:

that the authority of Scripture is founded on its being spoken by God.

Section 5, in true apostolic style, brings yet another ‘Last and necessary conclusion’:

that the authority of Scripture is sealed on the hearts of believers by the testimony of the Holy Spirit.

Inst. I:7,2 had already dismissed the idea of a church-sanctioned text, such as demanded by Rome:

for if the Christian Church was founded at first on the writings of the prophets, and the preaching of the apostles, that doctrine, wheresoever it may be found, was certainly ascertained and sanctioned antecedently to the Church, since, but for this, the Church herself never could have existed. Nothing therefore can be more absurd than the fiction, that the power of judging Scripture is in the Church, and that on her nod its certainty depends. When the Church receives it, and gives it the stamp of her authority, she does not make that authentic which was otherwise doubtful or controverted but, acknowledging it as the truth of God, she, as in duty bounds shows her reverence by an unhesitating assent.

Calvin, or his translator, is fond of the word ‘astrict’, a binding more powerful and positive than ‘restrict, so that we must learn from Inst. IV:8,5 that:

the Church (is) astricted to the written Word of God. Christ the only teacher of the Church.

From his lips ministers must derive whatever they teach for the salvation of others.

And in Inst. 1:6,1 he gives almost a doxology:

God therefore bestows a gift of singular value, when, for the instruction of the Church, he employs not dumb teachers merely, but opens his own sacred mouth; when he not only proclaims that some God must be worshipped, but at the same time declares that He is the God to whom worship is due.

Calvin held a very simple ‘two-voice’ view of truly Scriptural preaching (Inst. IV:1,5):

Those who think that the authority of the doctrine is impaired by the insignificance of the men who are called to teach betray their ingratitude; for among the many noble endowments with which God has adorned the human race, one of the most remarkable is, that he deigns to consecrate the mouths and tongues of men to his service, making his own voice to be heard in them.

Let another two statements settle the mind as to Calvin’s view of Scripture:

If, then, we would consult most effectually for our consciences, and save them from being driven about in a whirl of uncertainty, from wavering, and even stumbling at the smallest obstacle, our conviction of the truth of Scripture must be derived from a higher source than human conjectures, judgements, or reasons; namely, the secret testimony of the Spirit. Inst. I:7,4

There are other reasons, neither few nor feeble, by which the dignity and majesty of the Scriptures may be not only proved to the pious, but also completely vindicated against the cavils of slanderers. These, however, cannot of themselves produce a firm faith in Scripture until our heavenly Father manifest his presence in it, and thereby secure implicit reverence for it. Then only, therefore, does Scripture suffice to give a saving knowledge of God when its certainty is founded on the inward persuasion of the Holy Spirit. Inst. I:8,13

Text and Translation←↰⤒🔗

As early as 1535 Calvin was asked to revise cousin Olivetanus’ French Bible. Pierre Robert had been commissioned by the Waldensian Church to translate the Bible into French (now there’s a story!). This appeared in 1535 with a Latin preface by Calvin, a wonderful preview in précis of the early Institutes. Savour this:

Scripture is also called gospel, that is, new and joyful news, because in it is declared that Christ, the sole true and eternal Son of the living God, was made man, to make us children of God his Father, by adoption. Thus he is our only Saviour, to whom we owe our redemption, peace, righteousness, sanctification, salvation, and life; who died for our sins and rose again for our justification; who ascended to heaven for our entry there and took possession of it for us and (it is) our home; to be always our helper before his Father; as our advocate and perpetually doing sacrifice for us, he sits at the Father’s right hand as King, made Lord and Master over all, so that he may restore all that is in heaven and on earth; an act which all the angels, patriarchs, prophets, apostles did not know how to do and were unable to do, because they had not been ordained to that end by God.14

In his Commentaries and Lectures Calvin was careful of his text, very much aware of the burgeoning scholarship and the beginnings of a healthy pursuit of the Greek and Hebrew texts. Luther had used the Brescia edition of the Hebrew text, which was obviously thus available to Calvin, as was the Complutensian Polyglot — this Delitzsch thought to have been used by Beza, and so why not Calvin? The Soncino editions (1488), and the Bomberg editions (1518-1526), together with three editions of the Münster (1534, 1536, 1546), were all extant. None of these Hebrew texts differed greatly from the Brescia edition mentioned first.

For the New Testament Calvin certainly used that of Erasmus, the 4th edition, Greek and Latin folio of 1527 (there is a handsome copy, one of my favourite volumes, in the TBS library). He was not a mere follower of others in scholarship, but positive in his examination and choice of variants. The influence of Stephens and Colinaeus is to be found. This may sound a little startling, accustomed as we are to be suspicious of the ‘eclectic text’ stable, but we must accept the ground-breaking nature of textual scholarship for the Reformation translators and commentators, and not insist on their following terminology and principles which were only just beginning to be discerned and formulated. ‘Once Calvin had established the best text, he almost always translated directly from that original Greek text. He knew and used the Vulgate, but he did not trust it in the way that he trusted the original. Only rarely did he depart from the Greek text’.15 With reference to other commentaries and versions, Calvin’s most thoroughgoing deprecation is ‘frigid’. In this he seems to mean lacking the power or authority to quicken living faith: the favoured praise is ‘solid’, able to bear, to carry — a sure foundation.

Calvin loathed the allegorical way of interpreting, which led to his commentaries being attacked.

The reason for such attacks was, of course, Calvin’s insistence on attending to the ‘genuine sense’ of Scripture. Then, and still now, five hundred years later (tell it not in Gath!), allegorical methods of interpreting Scripture, however disguised or denied, provide Christians with a favourite means of making the Bible into a religious book of their own liking.16 Demanding the superiority of the original meaning of a text, Calvin appeared to deprive some orthodox Protestants of many of their already established ‘proof texts’.17 To them he even seemed to undermine the traditional doctrine of Biblical authority.

Reflections←⤒🔗

J.I Packer writes of Calvin:

He was ruled by two convictions that are written on every regenerate heart and expressed in every act of real prayer and real worship: God is all and man is nothing; and praise is due to God for everything good. Both convictions permeated his life, right up to his final direction that his tomb be unmarked and there be no speeches at his burial, lest he become the focus of praise instead of his God. Both convictions permeate his theology too.

And again, tellingly,

The amount of misrepresentation to which Calvin’s theology has been subjected is enough to prove his doctrine of total depravity several times over.18

What, for instance, of those who named their dogs after him so that they might kick and mock them!

John Calvin’s influence was widespread, and Geneva was certainly something of a ‘Bible hub’ for translation and for publishing. The story of the English Geneva Bible, 1560, is but one example of what was accomplished in that city, where Miles Coverdale served as an assistant to John Knox in the English congregation (surely, there were giants in the land). French Bibles and Italian Bibles were among the works of Calvin’s gathered disciples in Geneva, in and after his own lifetime. Erasmus and Beza published their continuing editions of Greek and Latin texts. When we move to the realm of influence, there is scarcely any limit. Calvin gave advice to Edward VI on the English Prayer Book, and very few of the men on the later 1604-11 translation committee for the AV were unaffected by the Geneva publications of Calvin and Beza, at many levels. Writing about the Dutch Statenvertaling in 2006,19 I remarked that for the Dutch Bible ‘the need to take up the original languages as the ground-text was becoming pressing. English, French and Italian versions, notably those originating in Geneva, though often printed in Amsterdam-Antwerp, had already taken this step’. The direct influence of Calvin’s Geneva on the Statenvertaling, almost seventy-five years after Calvin’s death, is quite strong.

A declaration that I have seen in many modern popular sources, in slightly varying forms, is this: ‘If Luther sounded the fanfare for reform, Calvin orchestrated the score by which the Reformation became a part of Western civilisation’. As a summary we may take the general point, but, as my American colleagues might say, it is more cute than convincing. For myself as a focus I would single out Calvin’s own formulation of the toweringly distinctive reforming principle embraced across Europe in the 16th century,

The unerring standard both of thinking and speaking must be derived from the Scriptures: by it all the thoughts of our minds, and the words of our mouths, should be tested. Inst. I:13,3

How far Calvin then, or Calvinists now, fulfil this, is a matter still fiercely, if too often ignorantly, debated!

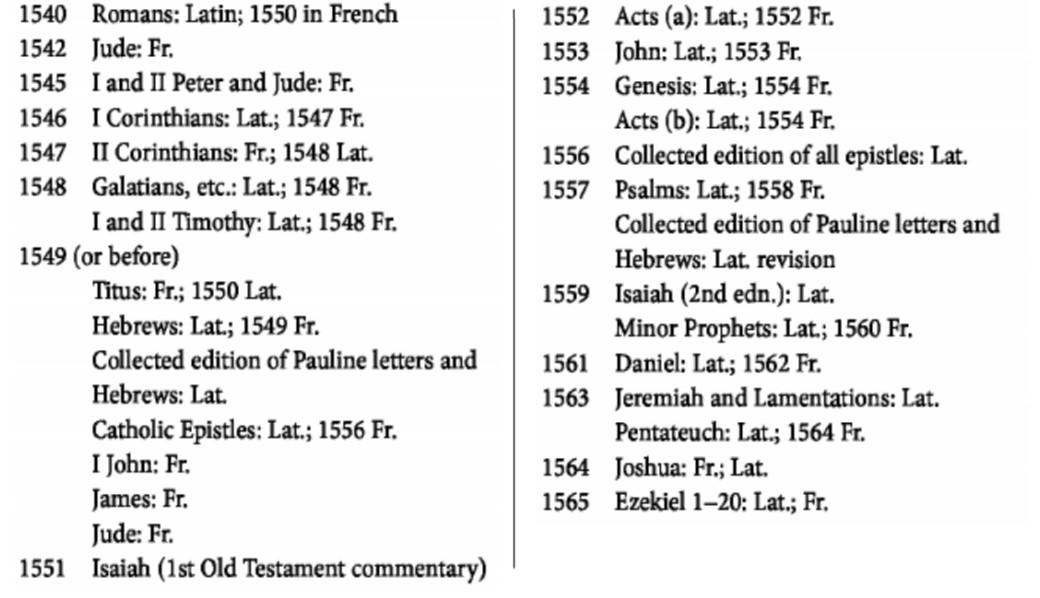

Appendix One: Calvin’s Commentaries←⤒🔗

A simplified list of Calvin’s Commentaries;

Published notes of Sermons and Lectures not included here20

Appendix Two: Calvin and Servetus←⤒🔗

By C.P Hallihan and D.E. Anderson, with contributions from Paul Rowland, General Secretary, and additional historical material supplied by Malcolm Watts, Chairman of the General Committee of the Society.

With what malignity some virulent ones imagined and stated that we wished him (Servetus) to be put to death, you are yourselves our best witnesses. To refute such calumnies until they shall have vanished by contempt and tranquil magnanimity, is the becoming duty of gravity and prudence.21

The execution of the Spanish-born scholar Michael Servetus — Miguel Serveto — was used to denigrate Calvin in his own time, and ever since; to write about Calvin without mention of Servetus leads to suspicion of dodging the issue. In our article, trying to keep to Bible issues, Servetus is not without significance, so the issue will be joined!

Born in 1511 (or perhaps as early as 1509), Servetus was raised in Villanueva (Tudela) near Aragods chief city, Zaragoza. In the tradition of Spanish-Moorish scholarship and culture, young Miguel proved a genius: by the age of thirteen, he had mastered French, Greek, Latin and Hebrew. At fourteen he was at the University of Zaragoza. Its leading scholar was Juan de Quintana, a Franciscan monk much influenced by Erasmus.

Aged sixteen, Miguel was sent to study law at the University of Toulouse, France, where the reading of Biblical texts in Greek and Hebrew revealed how much these earlier texts differed from the Vulgate. Trouble in the Papacy had left the Pope imprisoned, and in 1530 Charles V22released him on condition of an elaborate ceremony to confirm Charles as Holy Roman Emperor. Rome was in ruins so the ceremony was held in Bologna, where, among the guests, were Juan de Quintana and his secretary, Michael Servetus. Servetus was appalled by the full-on experience of court and papal practices,23 and in 1530 made his way to Basel and the Protestants. We know that he stayed for months with Oecolampadius, a local pastor, and having worn out his welcome with endless controversy, moved to Strasbourg in 1531. There, aged twenty, he published The Errors of the Trinity. This provoked the wrath of Catholic and Protestant authorities equally. They all banned the book, wanting Servetus arrested for heresy. His attempt at conciliation with Dialogues on the Trinity pleased nobody, and the Spanish Inquisition condemned him to death in his absence.

Miguel Servetus disappeared to Paris, assuming the name of his birthplace, and as Michel de Villeneuve studied medicine and mathematics. Work as an editor enlarged his expertise in many fields, including geography24 and Biblical criticism.25 Amongst his student acquaintances was John Calvin, who well may have written Cop’s address (see above), and as Servetus fled to Paris, so Calvin fled from Paris — but they were known to each other. During the next year Calvin risked his security in returning to Paris and Servetus to take up the theological challenges but they did not meet.

Michel de Villeneuve moved to Vienne in the Rhone valley of France, and for twelve years edited scholarly texts, practised medicine, and wrote on medical topics. From study of dissected bodies, Servetus identified the major role of the lungs in aerating the blood. Galen’s 1,300-year-old theory was that this was done in the heart; now, a century before William Harvey, Servetus had correctly described the pulmonary blood flow. But Servetus was a heretic, his works banned, and his medical achievements were not acknowledged.26 In his spare time Villeneuve (Servetus) prepared his treatise, The Restoration of Christianity, and in 1546 began a doomed secret correspondence with his old acquaintance John Calvin. These letters challenged Calvin’s theology: not only in regard to the Trinity, but also to the absolute truth of Scripture, predestination, and depravity.

Calvin’s early theological writings had not majored on the Trinitarian nature of the Godhead, and Pierre Caroli, a contemporary reformer, had accused him of being Arian. Calvin was cleared by a synod at Lausanne, but was subsequently on guard, ready to deal severely with Trinitarian deviations. At this time Servetus sent Calvin a manuscript of his unpublished Christianismi Restitutio — The Restoration of Christianity. Calvin sent in reply a copy of the Institutes; this was returned, with Miguel’s abusive marginal annotations. Calvin broke off the correspondence, but wrote to Farel in 1546 that if Servetus ever came to Geneva, Calvin would not assure him safe conduct: “‘Servetus recently sent me with his letters a new volume of his ravings ... He would come here if I agreed. But I will not give him my word; for if he came, as far as my authority goes, I would not let him leave alive”’27 — this last sentence appears ominous, if not unduly severe, but as T. H. Parker rightly observes28 it may be read as a threat or as a warning (and if the latter, perhaps one already conveyed to Servetus).

Servetus then published The Restoration of Christianity in 1553, his call to a return to what he viewed as the Gospels and away from the dogma of the Trinity — his Restitutes to counter Calvin’s Institutes.29 It also included the pulmonary blood circulation theses, and his correspondence with Calvin.30.His refutation of Galen was viewed as being equally heretical as his anti-Trinitarianism, and so was his repudiation of infant baptism.

Guillaume de Trie, a Protestant refugee from Lyon, was in correspondence with his Roman Catholic cousin Antoine Arneys in Vienne, and commented that while Rome was burning Reformers, a man living in Vienne, Michael Servetus, “‘calls Christ an idol and destroys every foundation of the faith, yet he is not punished for it’”,31 stating “‘I see, thanks to God, that vices are better corrected here than they are in all your officialities’”.32 According to de Trie, Servetus was a heretic “‘who well deserves to be burned”’.33 His cousin demanded proof of de Trie’s accusation, and shortly thereafter Servetus was called to appear at a special hearing to discuss the accusations — which charges he vehemently denied.

De Trie requested Calvin to release the letters between himself and Servetus. After much hesitation, against his will, he gave him several of the Spaniard’s letters, which de Trie sent to his cousin, writing that “‘It took a lot of pain to get these letters’”.34 Calvin, as was normal at that time, believed that blasphemies should be punished, and had been well aware of Servetus’ whereabouts and knew both his real and assumed identities as well as his heretical notions. But as de Trie noted, Calvin “‘would prefer to check the erroneous ideas by teaching than by persecution. He finally gave in when I told him that without his help I would be accused of blackmailing.”’35 De Trie notes of Calvin that ‘“it seems to him that his duty is to convict heresies by doctrine rather than pursue them by such a means, since he does not hold the sword of justice.”’36 Thus, in April 1553 Servetus was put on trial by the French Inquisition in Vienne. He was imprisoned, found guilty of heresy and condemned to burning, but managed to jump from a balcony into a courtyard where he found an unlocked door. He hid himself for several months, but then set out for Italy, and determined to go via Geneva.

Servetus went to Geneva almost certainly looking to the Libertines (Calvin’s great ‘antagonists’, who had helped with the printing of Servetus’ Restoration and at the time held the majority in the Council of Geneva37) for sympathy and support, which support would have certainly endangered the whole work of Reformation there.38 He was recognised in church and, as required by constitutional law, his presence was reported to the Council of Geneva, who had him arrested.

Calvin was out of the Council’s favour at this time and, in fact, had tendered his resignation just three weeks before the Servetus affair. Francois Bonivard wrote: ‘Calvin’s enemies ... had at that time gained control in the city’39Now ‘it was the city council who ... took over the case, and prosecuted Servetus with vigour’.40 Ami Perrin, Calvin’s enemy, was a leader during this time and was in direct conflict with Calvin during the whole period of the trial, and thus Calvin ‘could in no way have influenced the Council against Servetus’.41

Servetus was tried again for anti-Trinitarianism and for opposing infant baptism, the Council insisting that he was a heretic. Calvin was called to the Council to stand against Servetus, and had a list of thirty-eight heresy charges against Servetus as well as the correspondence he had received. But ‘the battle was fought solely for the cause, not the person of Servetus whom (Calvin) did not hate. He testified to this several times ... And he did everything to lead the mistaken man to the truth’.42

Servetus, for his part, believed that circumstances would bring what he most desired: the overthrow of Calvin and his religion, and a hearing for Servetus’ view on Trinitarianism. He complained to the Council on 15 September that Calvin, “‘for his own pleasure wants to make me rot here in prison’”.43A week later he sent to the Council:

Therefore, gentlemen, I demand that my false accuser be punished, poena talionis, and that he, like me, be imprisoned until the trial be decided either by his or my death or by some other punishment44

and demanded that he be given Calvin’s goods in restitution.45

The Council, however, had written to the other Swiss states, seeking their opinion of Servetus and his views, perhaps hoping that the animosity those states might have toward Calvin would sway them to Servetus’ side. Instead the Council was urged to ‘“stop the evil’”; ‘“If he persists in his folly, then use the power which is entrusted to you by God to prevent him by force from any further injury to the Church of Christ”’. The replies had been received and translated by 20 October. ‘It was the opinions of the German-Swiss confederates which, although they shrewdly circumvented the word execution, sealed Servetus’ death sentence’.46 On the 26th, the Council met, and at the end of their deliberations proclaimed:

Inasmuch as you, Michael Servetus of Villanueva in the Spanish kingdom of Aragon, have been accused of terrible blasphemies against the holy Trinity, against the Son of God and other principles of the Christian faith, whereas you have called the Trinity a devil and a monster with three heads ... We the mayor and judges of this city, having been called to the duty of preserving the church of God from schism and seduction, and to free Christians of such pestilence, decree that you, Michael Servetus, be led to the place Champel and be bound to a stake and with your book be burned to ashes, a warning to all who blaspheme God.47

With the medieval, early modern, joining of state and church, heresy was equivalent to treason, and from Constantine on, church authorities were agreed that the penalty for heresy48was burning at the stake — that despite any extenuating circumstances or personal opinion. ‘Geneva’s city council did far more to steer Servetus’ trial, sentence, and burning at the stake. Calvin asked the council for a more humane execution — beheading instead of the stake — but his appeal was denied’.49

Farel was with Servetus — to reclaim him — when Servetus learned of his sentence.50 Farel desired Servetus to see Calvin, and Calvin sought the Council’s permission to visit the condemned man in order to help him spiritually. When he eventually did see Servetus, he urged him to ‘ask pardon of the Son of God, whom you (Servetus) have degraded’.51

Calvin wrote to a friend, ‘We endeavoured to change the manner of execution; why we achieved nothing, I shall tell you orally’.52The sentence was carried out on 27 October 1553.53 Calvin did not attend the execution.54

In some ways, of course, the Reformers of the time — who sought, often with their own blood, to restrain the corrupting of theology that had so often poisoned the Church — would have been glad of Servetus’ death. This is the difficulty for modern readers, but such use of the sword as an instrument of state/church government was prolific at that time, Protestant or Papist. It cannot lightly be condemned nor commended from five hundred years on without some attempt to understand, and if not to forgive,55 then to be compassionately careful of casting thoughtlessly labelled stones. Was Servetus a heretic? By the plainly professed tenets of Rome, Geneva, and Wittenberg, the answer can only be yes. Was he a threat to Gospel faith and testimony? He utterly rejected the doctrine of original sin and therefore the entire concept of salvation being forgiveness of sins in the Blood of Christ; he denied the Reformers’ doctrines of Christ’s nature, and the vicarious atonement effected by His death. The Trinity was at best simply an ‘economy’ (contrivance?) of revelation, at worst a three-headed Cerberus, and Christ did not always exist.

Undergirding this was his withholding of assent to the full sufficiency and authority of the Bible. Would any pastor today be indifferent to the presence of such teachings within his flock, learnedly, fluently and yet abrasively and damnably insisted on? I think not. Servetus was a danger; adjust the Godhead to the creature mind, and Sovereign Grace salvation goes, and the whole intellectually bacchanalian baggage of Pelagianism has free course. Diminish or demean the sovereign sufficiency of Scripture and there is nowhere for ravens or doves ever to find a place for the feet (Genesis 8:9).

According to his own character and times, Calvin sought to instruct ‘those that oppose themselves; if God peradventure will give them repentance to the acknowledging of the truth’ (2 Timothy 2:25).56 Should heretics ever be persecuted to death, with or without the magistrate? In Rome, Geneva, London or New England, then or now, my own answer must be a humble but resolute ‘No’, an answer which was quickly heard in Calvin’s own day. The familiar Protestant pamphlet war began, for and against Calvin, and Sebastian Castellio wrote tellingly that ‘to kill a man is not to protect a doctrine; it is but to kill a man. When the Genevans killed Servetus, they did not defend a doctrine; they but killed a man’.57

In connection with our Bible thread you may like to know that still in the 19th and 20th centuries, Bible translation work in Poland, Transylvania,58 and, to a lesser degree, Hungary, suffered much from the damaging influence of Unitarianism, legacy of Servetus. Contemporary Unitarians seem not to regard Servetus as a true precursor, though they admire much about him; not so much a Unitarian, they have said, as a very unorthodox Trinitarian. Whatever next!

For more information, you might like to read W K. Tweedie’s Calvin and Servetus (Edinburgh, Scotland: J. Johnstone; London, England: R. Groomsbridge & Sons, 1846).

Add new comment