Riddles around the Letter to the Hebrews

Riddles around the Letter to the Hebrews

Part 11 ⤒🔗

The letter to the Hebrews is, according to Klijn, “the most enigmatic of all the writings of the New Testament”.2 It ends like a letter, but it lacks the beginning typical of a letter. The author’s name is absent, but he clearly has a good relationship with the readers; he hopes to meet them personally (Ch. 13:23b). And yet, the community of believers to whom this letter is addressed is not identified or located in any way. This is all very puzzling.

At the same time, there can be no doubt that the letter to the Hebrews is a text of great theological significance, as for example when it discusses the reconciling work of Jesus Christ, and the function of the new covenant as a fulfilment of the earlier covenant relationship between the God of Israel and His people. Even though some of the questions that arise may be left unanswered, a study of the so-called introductory problems of the letter is definitely worthwhile. The three greatest riddles we find in Hebrews are these: Who is the author? Who are his audience? What is their situation? In this article, and in the one to follow, I will attempt to find – as far as may be possible – a coherent answer in the development of the congregation of Jerusalem during the ‘sixties’ of the first century AD.

The First Riddle: Who is the Author?←↰⤒🔗

In the textual tradition, the anonymous letter to the Hebrews has generally been handed down together with the Pauline epistles, such as in Papyrus 46 (between Romans and 1 and 2 Corinthians) or in the Codex Sinaiticus (between 2 Thessalonians and 1 Timothy).3

Still, at an early stage there must have been doubts concerning its Pauline authorship. Origen points out differences in style and lines of reasoning (he does add, however, that the lines of reasoning in Hebrews are by no means inferior to those of texts that Paul did write). “Only God truly knows who committed this letter to paper”, says Origen. That does not keep him, though, from listing Luke or Clement of Rome – as well as Paul – as possible authors (see Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History VI 25, 11-14). It makes sense to link these names to the letter to the Hebrews. Clement of Alexandria suggests that Luke might have been the translator of a letter originally written in Hebrew by Paul (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History VI 14, 2). And Clement of Rome is the first of the church fathers to directly quote from Hebrews.

Even Calvin was not at all convinced of its Pauline authorship. This is clear from the introduction to his Commentary and from his explanation of chapter 13:23. According to Calvin, the letter to the Hebrews was not written till after Paul’s death.

Not Paul←↰⤒🔗

Aside from its stylistic features and its lines of thought – already pointed out by Origen as reasons to doubt its Pauline authorship – there are two important arguments to support the view that Hebrews was written by someone other than the apostle Paul:

Hebrews lacks the introduction that is characteristic of Paul’s letters: “Paul, an apostle of Jesus Christ”. Nowhere in this letter does the author identify himself as an apostle. This argument remains valid, even if we regard the conclusion of the letter (Ch. 13:22-25) as a brief ‘covering note’, separate from the letter itself (as Vanhoye argues), so that the conclusion at any rate was to have been supplied by Paul himself. For this conclusion is not an appendix: it is rooted in the final chapter, and hence in the whole letter.4

The letter itself states that its author, like his audience, did not belong to those who could give a first-hand testimony to Jesus’ words (see Ch. 2:3-4: he presumably means the apostles, referring especially to their unique testimony after Pentecost).5 In contrast, Paul is eager to bear witness to the Gospel that Jesus Christ Himself (and not people, Gal. 1:11-12) had revealed to him. This argument is not negated by the fact that Paul sometimes refers to the apostolic tradition (1 Corinthians 11:23; 15:3), for in those cases he explicitly presents himself as one of the links in the chain of revelation. On the other hand, the author of Hebrews appears to see himself primarily as a recipient of this tradition.

Possibly Barnabas←↰⤒🔗

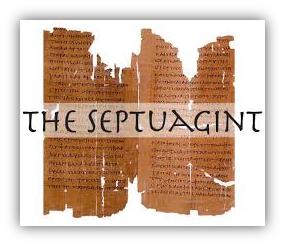

The textual tradition leads us to conclude that we should seek the author in Paul’s immediate circle. The document itself allows us to construct the following profile of the author: he was someone with literary gifts and a high degree of mastery of Greek, thoroughly familiar with the sacred Scriptures (the Septuagint), of Jewish background, someone who introduces himself to his audience as an authoritative teacher and interpreter of Scripture, possibly a companion of ‘brother Timothy’ (Ch. 13:23).

The one New Testament figure who best fits this description is Joseph, better known as Barnabas. He was a Levite, familiar with the rituals of temple worship, a Jew from the diaspora, born in Cyprus but living in Jerusalem (Acts 4:36-37). He was sent to Antioch by the congregation in Jerusalem, accompanied Paul on his first missionary journey, and was part of the delegation that presented the decision of Jerusalem to the congregation in Antioch.6 The fact that the apostles have named him Barnabas makes him an especially attractive candidate: he is typified as ‘the son of encouragement’ (Acts 4:36: huios paraklèseoos). This corresponds well with the fact that the author himself, at the end of his letter, describes it as a ‘word of encouragement’ (Ch. 13:22: logos paraklèseoos). Barnabas would have been especially suited to speak or write such a word of encouragement. It was not just in Jerusalem that he was known as a prominent personality. He also shows up as one of the teachers in the congregation at Antioch (Acts 11:26; 13:1), and throughout the early Christian church he was regarded as a person with authority (compare 1 Corinthians 9:6).

In the second century AD, no less a figure than Tertullian explicitly names Barnabas as the author of Hebrews. This appears to have been a widely accepted identification during this period, for Tertullian adds that this letter is more widely accepted in the churches than The Shepherd of Hermas, which he considers apocryphal (An exhortation to chastity, 20, 2).7 Besides, an anonymous letter from the time of the apostolic fathers is entitled The Epistle of Barnabas; the fact that this text is ascribed to Barnabas is best explained by the commonly held view that he wrote Hebrews, a critique of traditional Judaism.8

Neither Apollos nor Priscilla←↰⤒🔗

Two other possible candidates are not supported by similar evidence from the early church. The first is Apollos, a Jew from Alexandria, who is described in Acts 18:24 as ‘a learned man, with a thorough knowledge of the Scriptures’. Given the spiritualized interpretation of Old Testament cultic worship in Hebrews, the fact that Apollo is a native of Alexandria might argue for his grounding in the thinking of the Jewish philosopher Philo. However, there are too many theological differences between Hebrews and Philo to justify a direct connection.9 The second possible author is Priscilla, perhaps in collaboration with her husband Aquila. They had arrived in Corinth from Italy just before Paul, and he had found a place to live with them – like him, they were tanners – while he was in Corinth (Acts 18:2, 3). This could explain the greetings extended from Italy (Hebrews 13:24b), and it is quite understandable that a female author (or her immediate surroundings) would not have identified her by name.10 On the other hand, the author’s elegant rhetorical flourish: “I do not have time to tell about…” (Hebrews 11:32) contains a masculine singular participle (not me… dihègoumenèn but … dihègoumenon). In short, neither Apollos nor Priscilla appear to be likely authors of the anonymous letter to the Hebrews.

In summary: for reasons unknown to us, the author of Hebrews does not identify himself. Unlike Paul, he does not present himself as an apostle. He does, however, appear to be someone who was within Paul’s immediate circle. His authority within the early Christian church was unchallenged, especially when he was drawing directly on Scripture. Of all potential authors, Barnabas appears the most likely candidate. He was certainly no stranger in Jerusalem. Still, the questions surrounding the authorship of Hebrews cannot be resolved with any degree of certainty, and in the end, we can do little other than agree with Origen: only God knows who the author of Hebrews is.

The second part of this article continues with an examination of the possible readers to whom this letter was sent, and the historical situation in which they may have been living. How these questions are answered has implications for the way in which we understand the letter.

Part 211 ←⤒🔗

The three most outstanding riddles about Hebrews are: who is the author, who are his audience, and what was the situation? In the first instalment we concluded that it is difficult to identify the author. It may have been Barnabas. In this second instalment, we are able to discover rather more about the readers and their situation when we make the connection with the church at Jerusalem, from a redemptive-historical point of view our mother church.

The Second Riddle: Who are the Readers?←↰⤒🔗

It is likely that the author of Hebrews did, at some time, belong to the church he writes to. He asks them to pray for him, for he hopes that he may soon be restored to them, and he plans to visit them, together with brother Timothy (ch. 13:19, 23). At the time of writing, however, he is in Italy, from where he passes on greetings:

Greet all your leaders and all God’s people. Those in Italy send their greetings.ch. 13:24

He sends greetings on behalf of Christians living in Italy: from the church at Rome, and also from the churches in southern Italy that, apparently, had been established by this time (for example in Puteoli – see Acts 28:13-14).12 We can compare this greeting to that of Paul, when he writes to the church in Corinth: “the churches in the province of Asia send you greetings” (1 Corinthians 16:19).13 It appears, then, that Hebrews was written from Italy. This would then also explain how I Clement, written at an early date, is already familiar with this letter.14

It is possible that the letter’s puzzling superscription: ‘To the Hebrews’ (pros Hebraious) dates from the time when all of Paul’s letters were brought together, with no other purpose than to harmonize this letter with the other material in the collection. Still, almost every subsequent manuscript takes over this title ‘to the Hebrews’ as a subscriptio (it is to be found, for instance, in the codex Sinaiticus, the codex Alexandrinus and the Majority Text).

This expression ‘Hebrews’ refers to Jews who have come to confess Jesus as the Messiah. This is confirmed by the parallelism in the letter’s prologue: it compares the way God spoke to ‘our forefathers’ – the ancestors of Israel – and the way he speaks today through his Son to us, the descendants of these forefathers. The numerous references in Hebrews to the cultic worship of Israel would only have made sense to Jewish Christians. Just as was the author himself, his readers were part of the people of God, the heirs of what was promised, those who were called (ch. 4:3, 6:17, 9:15).

Superb Greek←↰⤒🔗

Why then is Hebrews written in superb Greek, and why are its quotations taken from the Septuagint? Barnett’s suggestion, that the readers of Hebrews were primarily Greek-speaking Jews, a continuation of the Greek-speaking community in Jerusalem referred to in the first half of Acts, has merit.15 In part, one suspects, because of their extensive network of contacts in the diaspora (greetings from Italy!). In any case, a letter written in Greek could also easily be distributed among the Jews in the diaspora.

If this identification – the readers were Jewish Christians living in Jerusalem – is correct, there are implications for the interpretation of certain key features of the letter. For then it had been the direct witness of the apostles that had brought these Jews to accept Jesus as Israel’s Messiah. The statement that God confirmed their message by ‘signs, wonders and various miracles, and gifts of the Holy Spirit’ corresponds with the events in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost. The experience of ‘earlier days’, when they were insulted and persecuted, and even had their property confiscated (ch. 10:32-34) reminds us of the wave of oppression in Jerusalem after the death of Stephen. The ‘leaders’, who proclaimed the Word of God, whose lives and the outcome of whose faith they had to consider (ch. 13:7), could well have been prominent men such as Stephen himself, and James, the brother of the Lord.

Even a passage such as ch. 4:4-6, which has always been difficult to interpret, could be explained in this historical context, as Geertsema has done. When they were converted, the readers had been enlightened by the Gospel; they had tasted the heavenly gift of Christ; they had shared in the Holy Spirit, who was poured out at Pentecost; their faith had been fed by the apostles’ preaching: forgiveness of sins and eternal life. If, knowing all this, they fall away, they subject Jesus (after all, the Jews in Jerusalem had loudly called for him to be crucified) to public disgrace by nailing him to the cross all over again. It is impossible for such a person to be brought back to repentance.16

In short: the readers of the letter to the Hebrews were Jewish Christians, probably living in Jerusalem. Perhaps that is why, at the conclusion of the letter, they are called ‘saints’ (ch. 13:24, ESV). Whether or not these ‘saints’ were actually living in the holy city is not clear. They receive greetings from the Christians in Italy. At the time of writing, the author was staying there. But, he says, he hopes to be restored to his readers soon.

The Third Riddle: What is the Situation?←↰⤒🔗

The key question, when dating the letter to the Hebrews, is whether or not the temple in Jerusalem was still in operation. In the letter, cultic worship is consistently described in verb forms that denote the continuing present. That may be no more than a literary convention (as, for example, in a cultic passage in I Clement 40-41). This letter, however, draws on existing cultic data when arguing that the readers are to seek their salvation in Christ who is in heaven. The writer argues, for instance, that the continuing sacrifices can never make perfect those who draw near to worship. If they could, he says, would they not have stopped being offered (ch. 10:1, 2)? If he had written his letter after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple, it is unlikely that he would have made his point in these terms. In other places, too, it appears that cultic worship is still alive and well (ch. 7:27-28; 8:3-5; 9:25; 10:8; 13:10).

Tent of Meeting←↰⤒🔗

For this reason it is hard to believe that this letter can be dated any time after AD 70.17 It is remarkable, though, that the writer nowhere refers explicitly to the temple. Instead, he continually goes back to the Tent of Meeting, and to the people of Israel during their time in the wilderness. He consistently portrays the cultic worship in Jerusalem in Old Testament terms. This is similar to what Stephen did in his address, and it may have served to relativize the importance of the temple, and to warn the Jews against misplaced pride (Acts 7). The sanctuary in Jerusalem is neither the beginning nor the end of meeting with God. If the old covenant is described as obsolete and aging (ch. 8:13), that must certainly include the Old Testament cultic worship that went with it. In constructing his argument, the author goes back to the Old Testament foundation of the temple worship. By highlighting the mobility and the temporary character of the Tent of Meeting, he makes his readers see that true worship has been moved to heaven. There, in the person of Jesus Christ the Son of God, it finds its resting place and final destination.18

The letter to the Hebrews was probably written during the period between the death of James, the brother of the Lord, and the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, that is between AD 62 and 70. In many respects, this was a time of crisis. The Jews who confessed the Messiah were severely oppressed by their nationalist compatriots. They are addressed with a ‘word of encouragement’ (ch. 13:22: logos paraklèseoos). The fact that the letter identifies itself in this way seems also to describe its character. Acts 13:15 shows us that delivering such a word of encouragement was customary in the synagogues: when Paul and Barnabas(!) came to Antioch in Pisidia, the leaders of the synagogue, following the reading of the Law and the Prophets, invited them to speak such a word to the congregation. Paul takes the opportunity to deliver a lengthy address, which culminates in the proclamation of Jesus the Messiah. It is entirely possible that both this sermon and the letter to the Hebrews are elaborations on a form of address that was customary in the synagogues.19 One might, then, read Hebrews as a sermon in written form, one that could span the distance, and which served to encourage the Jewish Christians of Jerusalem.20 The author wishes to create the impression that he is in the midst of the assembled church, and speaking to it directly and personally. He carefully avoids any reference to writing or reading; instead, he accentuates speaking and listening, (ch. 2:5; 5:11; 6:9; 8:1; 9:5; see also 11:32: “I do not have time to tell about…”). He often uses ‘we’ and ‘us’; from a distance he identifies with his unseen audience. He frequently uses rhetorical devices, and the dynamic within the letter is enhanced by regularly alternating instruction and admonition.

Series of Quotations←↰⤒🔗

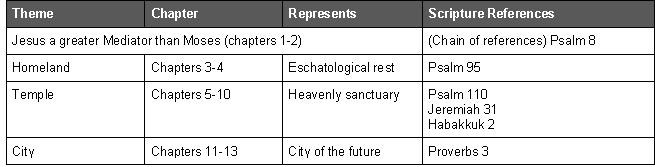

By means of frequent and sometimes extensive quotations, the author endeavours to let Scripture itself speak. He introduces the letter with a catena of Bible references, a series of quotations strung together like beads on a string, showing that Moses has been superseded by Jesus, to whom – according to Psalm 8 – everything is subjected. After that, three great themes follow, the themes that are characteristic and non-negotiable for orthodox Judaism: homeland, temple and city.21 Time and again, the author reminds his readers not to fix their eyes on what is earthly, but on what is in heaven. That requires a believing upward and forward shift in one’s thinking. In this context, he addresses all three themes:

- The ‘promised land’ is the eschatological rest, which we must still enter. After all, God’s promise of rest – to which Psalm 95 alludes when it recounts the message for the unbelievers in the wilderness, that they would never enter the Promised Land – still stands (ch. 4).

- Our ‘tent of meeting’ is the heavenly sanctuary, where Christ ministers as our perfect High Priest. He is a priest forever, after the order of Melchizedek (Psalm 110); he is the Mediator of a new covenant, one that causes the earlier one to be forgotten (Jeremiah 31). He is the One who is to come, the One who will not delay, the One who will save the righteous by faith (Habakkuk 2).

- The ‘city’ we look for is the city of the future, the heavenly Jerusalem. God the Father nurtures his children with discipline – according to Proverbs 3; the trials of this life are part of the school of faith, and may not discourage us.

This shift in thinking challenges the readers of Hebrews to stop orienting themselves on earthly certainties. Prepare yourselves for the loss of the earthly Jerusalem, the holy temple city. As perilous as the situation may become – land, temple and city are not non-negotiable. We can give them up. Our anchor is none less than the Son of God, Jesus the Messiah. He is a greater Mediator than Moses could ever be. Those who, in times of crisis, orient themselves on Him, will find the courage to leave the camp, to let go of their dearly-held Jewishness, and to leave Jerusalem (compare ch. 13:13-14).22 We have no enduring city here; Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever (ch. 13:8).

Conclusion←↰⤒🔗

The letter to the Hebrews aims to speak a word of encouragement in a time of crisis. It is a sermon in written form, which stimulates the reader to persevere in the power of faith, even when Jerusalem is overrun and the temple is destroyed. The anchor of Christian hope is not let down, but drawn up into heaven, where Jesus Christ is, the embodiment of our New Testament worship. The following table may assist in understanding this, by linking the chapter divisions and the Scripture references to the three great themes: homeland, temple and city.

Add new comment