Faith and Life in All Its Dimensions The Augustinian Tradition of Abraham Kuyper and Klaas Schilder

Faith and Life in All Its Dimensions The Augustinian Tradition of Abraham Kuyper and Klaas Schilder

The great church father, Augustine (354-430), in his Retractions, written at the end of his life, provides a brief description of the contents of his work, The City of God (Latin: De Civitate Dei). This great undertaking was at last completed in twenty-two chapters... Of these twelve (last) chapters, the first four contain an account of the origin of these two cities – the city of God, and the city of the world. The second four treat of their history or progress; the third and last four, of their deserved destinies.

Augustine Himself⤒🔗

According to Augustine, the course of human history is not merely an immanent series of events, within the material world, to be explained by phenomenal research and theories of purely immanental causation. History is rather seen as having a constant transcendent and eschatological dimension, interacting with invisible spiritual beings, evil and good, and moving on to our final destiny as human beings. According to Augustine, the ‘City of man’ is trying to achieve a blissful eternity with the help of the ‘gods’, whom he calls demons in disguise, whereas the ‘City of God’, is dedicating itself to ‘the eternal truths of God’, the Triune God of the Bible, looking forward to a restored, heavenly paradise through the grace of God in Christ.

We notice what Augustine highlights as the center of his work, The City of God: the hermeneutical conflict between the City of God and the City of man. Two different interpretations of the same events are taking place. While the City of man interprets the disaster of the fall of Rome and the threatening invasion of German tribes as a result of the enforced Christianizing of the Roman Empire, and the forbidding of polytheistic worship in the temples, Augustine, in service to the City of God, interprets these events differently. He sees these disasters as a continuation of the disasters which have marked all of human history since the Fall of man. They are the result of human sin, and are God’s way of chastening human beings, so that they might seek Him as He has revealed Himself. The eschatology of both cities is clear: ‘their deserved destinies’ (debitos fines). The hope of the City of man is that the gods can guarantee its eternal happiness. However, in the midst of this movement toward a final split destiny, hell or heaven, the tendency of the City of man is nevertheless to focus in an unhealthy way on ‘worldly prosperity’ (res humanae ita prosperari volunt). The City of God, in contrast, knows itself to be on pilgrimage, moving toward its own heavenly consummation.

However, the fact that the City of God is headed for the new creation, the merging of heaven and a renewed earth, does not mean that the journey is to be dismissed as a mere ‘parenthesis’. The City of God, along with the City of man, is ‘going outward’ (excursus) and ‘going forward’ (procursus). The City of God, by God’s grace, the City of man under the domination of Satan and the fallen angels. The City of man has its significant history, but so does the City of God. For the world is still God’s good creation. That is one of the insights that Augustine gained through his conversion from Manicheism, which saw the material world as evil. The world is good, but deeply influenced by evil, which is the absence of good. Evil feeds on good like a parasite, and cannot exist without it. Even Satan and the fallen angels were created good, and their guilt is compounded by that fact.

Augustine calls the citizens of the City of God to faith and work. Faith in the God of grace in Christ, and work in the sense of participation, in faith, in the City of man, in so far as that is spiritually and morally possible. That means witness: bringing, by the preaching of the Gospel, God’s light to the City of man, so that by God’s grace citizens of that city will change allegiance and join the City of God. It means, as well, political and cultural participation in the City of man, in the power and for the sake of the City of God. It is good that the Roman emperors chose for Christ, and tried to change the course of the Roman empire. Augustine hopes and prays that they will continue to choose for Him, until Jesus returns to judge the living and the dead.

Kuyper in the Augustinian Tradition←⤒🔗

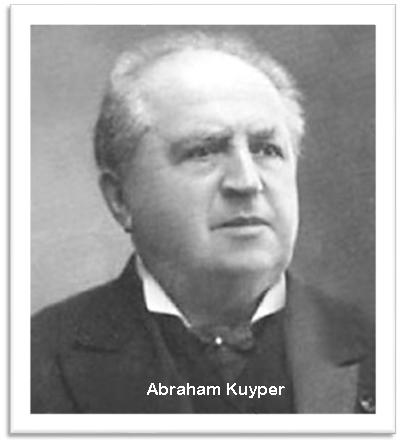

We can understand Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) as someone who appropriated and attempted a renewed application of the Augustinian tradition. Kuyper, first a theological liberal, then, by conversion, an orthodox Reformed man, sought paths of spiritual renewal for The Netherlands. He learned his theology by looking back to the Reformation, to the Reformed Confessions, and to the 16th and 17th century orthodox, scholastic Reformed theology. His allegiance to the Lord Jesus meant a growing allegiance to Scripture as God’s inerrant Word. He was glad to see around him believers, most of them simple folk, and mainly in the biggest church of the Afscheiding, the Christian Reformed church. However, he was not happy with the trappings of this movement: a preoccupation with adult conversion, based on theological and spiritual works of the 17th and 18th centuries, the ‘old writers’ (de oude schrijvers), and a deliberate cultural isolation from the ‘evil modern world’.

Groen van Prinsterer←⤒🔗

Kuyper was deeply influenced by his older friend, the politician and historian Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer (1801-1876), founder of the Anti-Revolutionary Party (a small group of politicians), and archivist of the House of Orange (the royal family of The Netherlands). Groen was an orthodox Reformed man (although he wrestled with the doctrine of God’s eternal election), someone who sought, consciously in the Augustinian tradition, to fight the good fight of faith, carrying on the great hermeneutical debate about life on earth. This meant to oppose the powerful movement of ‘the Revolution’ in The Netherlands and Europe, which since the French Revolution of 1789, was seeking to tear down all of Christian faith and replace it with ‘Reason’. Groen’s motto was: “Against the Revolution, the Gospel!” (“Tegen de Revolutie, het Evangelie!”)

Like Augustine, Groen attempted to use the spiritual weapons of the City of God to combat the City of man in its current form. This meant to unmask the supposed neutrality of rationalistic humanism, which was the driving force in the political movements of Conservatism and Liberalism, in the educational system of The Netherlands, up to and including all the universities, and in the academic theology of the Hervormde church. Liberalism in politics meant a laisser-faire capitalist approach to economics, but with no room for orthodox Christianity in education. Later, the more overt Revolutionary movements of Socialism and Communism would make their entrance on the Dutch scene, but already Groen pointed out the deep affinity between Conservatism, Liberalism, and Socialism. They all wanted to banish orthodox Christianity from public life, and assign it its safe place in the private quarters of the ‘backward and ignorant’. The Anti-Revolutionary Party, led by Groen, tried to give the City of God a vital voice in public life. Kuyper became Groen’s disciple and then his successor, after Groen’s death in 1876. The fight for the City of God would continue!

Kuyper: the Reformation of all of Life←⤒🔗

Abraham Kuyper, after his conversion in the 1860’s, moved more and more in an orthodox Reformed direction. However, he did this consciously seeking to participate in and eventually transform (so he hoped) the full breadth of social and cultural life in The Netherlands. This required a Reformation of the church (the Hervormde, official Protestant state church of that day), an intensification of the movement of the Anti-Revolutionary Party in politics, the establishment of truly Christian education, from day schools to the university, and the ongoing education of Christians by a daily newspaper and a weekly magazine. Kuyper, a genius and a man of tremendous energy, began this daunting task. In his work, Calvinism: the Stone Lectures of 1898, Kuyper showed how Calvinism had historically sought to transform all aspects of life. This legacy needed to be continued!

The Church and the Free University←⤒🔗

Although the chief church of the Afscheiding was of a considerable size (perhaps 250,000 members in the 1870’s), it was not ambitious to change Dutch society. In this it was less than Augustinian. This had to do with its pietistic origins. Kuyper loved and admired the ‘little people’ (kleine luyden) of the Afscheiding, but was dissatisfied with their pessimistic, almost fatalistic, attitude toward society. As far as the Hervormde church was concerned, the large state church with perhaps 3 million official members, Kuyper saw the potential of a Reformation movement. There were orthodox Reformed believers there, mainly, like the Afscheiding brothers and sisters, of the lower class and pietistic. Kuyper thought: if they could only be mobilized for Christ!

Kuyper, since his conversion, was more and more disgusted by the liberal theology of his day, and by the compromising spirit of theology Professors and ministers who were in some way orthodox, eventually called the ‘Ethical’ theology in The Netherlands. No! said Kuyper. We must return to God’s Word as the inspired, inerrant source of the Church’s life. Sola Scriptura! Jesus Christ, the crucified and risen, must once again be allowed to sit on the throne and rule His Church!

This eventually led to the Doleantie movement, initially within the Hervormde church, but finally breaking away from it in 1886. Kuyper wanted a return to Scripture, to the uncompromised authority of the Reformed Confessions, but sought also a new, contemporary approach to church life and doing theology. That was, for Kuyper, seeing life as an ‘organic’ whole. The fault of the ‘repristination’ theology of the Afscheiding was its purely conservative character: merely repeating what the Puritans of the 17th and 18th century had said. What was needed was a theology which took account of new insights of the modern era, and at the same time remaining completely orthodox. Kuyper developed his ideas of ‘presumed regeneration’ in connection with baptism in this context, as a more ‘organic’ way of seeing the covenant and God’s election in church life.

This was also the background to his founding of the Free University of Amsterdam in 1880, where he became Professor of Dogmatics. Here theology would be developed in an old-and-yet-new-way, Reformed but also Reforming. Not a mere repeat of the past, but a transformative theology for the modern age, “in rapport with the times.” And the theological faculty would be accompanied by other faculties, law, medicine, etc., so that eventually all the modern disciplines of the arts and sciences would be represented. A university to help transform The Netherlands!

The AR Party and Christian Day Schools←⤒🔗

Kuyper organized the more informal Anti-Revolutionary Party of Groen into a modern political party (the first in The Netherlands), in 1879. One of the great aims of Christian politics was the establishment of Christian education for the youth of The Netherlands, with equal rights for financial funding with the ‘neutral’ public schools. The battle was long and hard, but finally, three years before his death, in 1917, the law was passed granting Christian day schools fully the same rights to public funding as the ‘neutral’ public schools. One battle had been won, by God’s grace!

In the meantime, Kuyper had himself, by cooperating with the Roman Catholic political party, become Prime Minister of The Netherlands, from 1901 to 1905. And thereafter he remained the ‘grand old man’, the statesman seeking to support the development of the Reformed Churches, the ARP, and the Reformation in The Netherlands.

Christian Journalism←⤒🔗

In order to help educate the ‘small people’, who constituted the majority of the orthodox Reformed believers in The Netherlands, Kuyper established the daily De Standaard (The Standard) in 1872, after having to begun to write for the orthodox weekly De Heraut (The Herald) in 1869. He saw this, particularly his writing for De Standaard, as crucial. If ordinary Christians could be taught to see how the Lord Jesus claims all life for Himself, then there would be hope for a genuine Reformation of The Netherlands, not just in the church, but in all of life. The City of God was a City of insight and of action for the totality of life, and needed such organs to spread its light in The Netherlands.

←⤒🔗

←⤒🔗

Klaas Schilder←⤒🔗

Although Schilder was eventually an opponent of Kuyper on a number of key issues (the nature of the church, common grace, and baptism), he can still be seen as someone standing in the Augustinian, and also in the Kuyperian tradition. The violent ‘hermeneutical conflict’ between the City of God and the City of man, continues in the fiery polemics of Klaas Schilder. Schilder was an Augustinian by his commitment to the Reformed Confessions, which were deeply influenced by Augustine’s commitment to the saving Lordship of Jesus, to the supreme authority of Holy Scripture, and to God as sovereign in election and providence. He was also indebted to Kuyper for Kuyper’s vision of a Reformed orthodoxy which was not content to repeat old formulas, and to Kuyper’s vision of Reformed faith which needed to reach and transform all of life.

Concretely we see Schilder, as a preacher, and in that work as a creative theologian, preaching the Word of God as the story of salvation history. This was certainly a new way of preaching in his day, which evoked criticism from some. Wasn’t this almost exclusive emphasis on God’s saving work in the history recorded in the Bible going to mean less emphasis on the need for personal conversion and personal piety? Schilder disagreed. He felt the focus on personal conversion had become stereotyped and hollow in repeating the method of the old Puritans. The Word of God had to be opened anew, to see Christ at the center of the Gospel, that is, the whole Bible, and not the christian, in his or her conversion experience.

Schilder was, like Kuyper, a brilliant journalist, writing for the weekly De Reformatie (The Reformation) from 1920, and eventually its sole chief editor. At first Schilder was hesitant about the direction he wanted to take as a writer, but eventually he managed to combine, like Kuyper, a commitment to orthodoxy (concurring with the rejection of Geelkerken’s moderate liberalism), a rejection of compromising ‘neo-orthodoxy’ (Barth), with a critical look at the Reformed theological tradition, eventually trying to purify it of ‘scholasticism’ and the influence of neo-Platonism. In the latter effort he was joined by the philosophers H. Dooyeweerd, D.H.Th. Vollenhoven, and the schoolteacher, A. Janse.

Schilder was, like Kuyper, a Professor of Dogmatics, starting in 1933 in Kampen. He lectured and wrote, and eventually began his opus magnum, a commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism, just before the start of the Second World War and only finishing the fourth volume, when he died prematurely, aged 62, in 1952. Unlike Kuyper, Schilder was not directly involved in the development of a Reformed university or of Christian day schools, although after the “Liberation” (Vrijmaking) of 1944, he supported the founding of Reformed schools committed to the principles of the Reformation of the church in the Liberation.

Similarly, Schilder was not directly involved in politics, although after the Liberation he did see the need for, and supported, a new, fully Reformed political party, the Gereformeerd Politiek Verbond (Reformed Political Association) in 1948.

In his little book Christus en Cultuur (Christ and culture), Schilder spoke as Kuyper had done, of Christ transforming all of culture. However, he did this without the broad, cultural scope of Kuyper, saying finally that the elder doing house visitation is much more a force for cultural change than all the ‘high-culture’ of the elite in society. In this, he was perhaps being resentful toward the ‘rich and famous’, and not ambitious enough. We do not read anything about art, for example, a subject Kuyper devoted attention in his book Calvinism.

Schilder revived and vitalized the ‘transcendent’ and ‘eschatological’ dimensions of the City of God, enunciated by Augustine, in its spiritual struggle against the City of man. This meant, concretely, he had to oppose Nazi and Socialist influences in the churches in the 1930’s and, when the Germans invaded in 1940, to write polemically against the German Nazi political movement, now occupying The Netherlands.

Lessons from Kuyper and Schilder←⤒🔗

Kuyper and Schilder, in the Augustinian tradition, are inspiring figures. They have their own weaknesses and shortcomings, and they were ‘dominant personalities’ who tolerated little dissent from their immediate peers. They are striking figures in the 19th and 20th century due to their commitment to Reformed orthodoxy, while seeking Biblical renewal and rethinking of dogmatic subjects. They are striking figures in calling for Reformation in all of life, starting with the church. They can inspire us in our day to follow their example in seeking to be Augustinians in our own settings in the 21st century. I believe that churches on all continents can learn a lot from Kuyper and Schilder, and going back, from Augustine himself. Reformed faith at its best is orthodox, but also Biblically progressive. Reformed faith seeks continuing Reformation of the church (semper reformanda), and seeks the unity of the church. The latter emphasis is by Schilder in particular vigorously proclaimed and tried to put into practice.

Reformation faith is City of God faith, on pilgrimage to the coming, beautiful City with its twelve gates, yes, but therefore “standing up for Jesus” in all areas of life, until He returns.

Add new comment